Partnerships in Public Sociology: Expanding Voting Rights for People with Felony Convictions

Christopher Uggen

Last fall the Sentencing Project released Locked Out 2022, the fourth in a series of public reports on U.S. felony disenfranchisement prepared in a partnership with my academic research team (Uggen, Larson, Shannon, and Stewart 2022). Disenfranchisement here refers to the practice of denying voting rights to people convicted of felony-level criminal convictions. The United States has long been distinctive for both its unusually harsh disenfranchisement laws and for the significant share of its population that is affected by them (Manza and Uggen 2006). In the past five years, however, the movement to reenfranchise people with criminal records has gained real momentum.

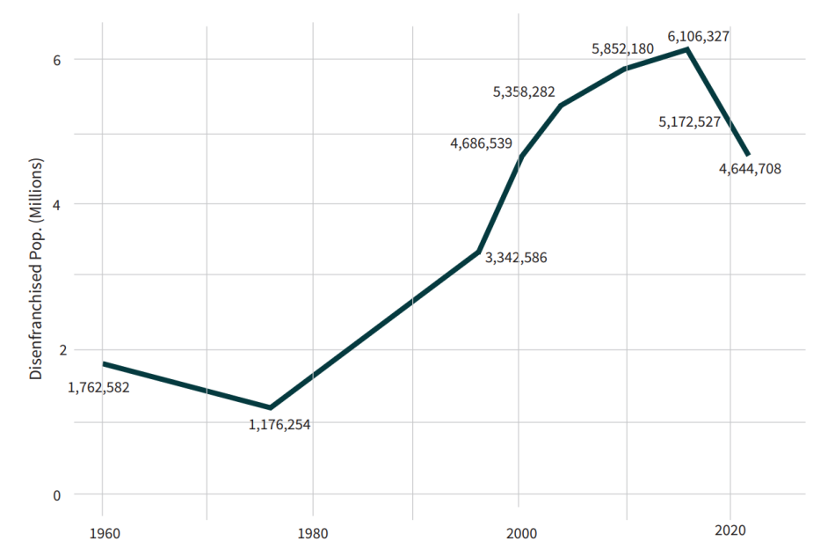

Our latest report tells the tale of these two trends. On the one hand, over 4.6 million people remain disenfranchised in the United States – or about the same number that we estimated in 2000. Moreover, illegal voting prosecutions, intimidation, and suppression appear to be on the rise. On the other hand, more states have extended voting rights to more people convicted of felonies, resulting in the reenfranchisement of about 1.5 million people since 2016.

This figure and many of those that follow were drawn from the Locked Out 2022 collaborative research report with the Sentencing Project. The Sentencing Project is a non-partisan 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization whose mission statement is well-matched with my own priorities in public work: to advocate for “effective and humane responses to crime that minimize imprisonment and criminalization of youth and adults by promoting racial, ethnic, economic, and gender justice.”

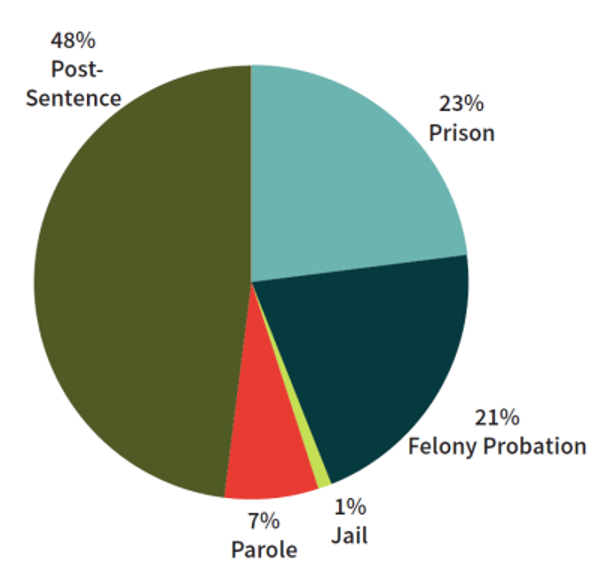

Much of the rise in disenfranchisement since 1975 has been driven by racialized mass incarceration and mass probation across the United States. In recent years, however, there have been some big legal changes: more states are restoring the vote, both to people who have completed their sentence, and to people on probation or parole for felonies. In only two states, Maine and Vermont, do people serving prison time for felony offenses retain the right to vote. Taken together, our report shows that only about one-fourth of the 4.6 million people disenfranchised are currently incarcerated.

It is hardly the time for a victory lap, but the recent progress is undeniable – eight states have expanded voting rights in the last two years alone. As of this writing (February 2023), the Minnesota Senate has passed a bill restoring the vote to non-incarcerated populations and, as Caroline Sullivan reports in Democracy Docket, 18 other states are currently considering such bills.

To the extent that our team’s academic research has played any part in these reforms, it is undoubtedly due to partnerships with key institutional actors such as the Sentencing Project. These groups have a direct connection to media, activists, and grassroots organizers that academic researchers lack. The goal of this essay is to show how and why effective public scholarship often requires a team effort, and a real connection between researchers, institutional partners, and a diverse set of publics.

There are many varieties of partners and relationships, though my focus is a particular partnership between a research team and a non-profit advocacy organization, a case chosen for its longevity and impact. After some background on the scholarly and public project, I will discuss the halting and piecemeal path to legal and policy change. My main purpose in writing, however, is to share information that may be useful to other scholars considering such collaborations. In doing so, I will try to identify potential pitfalls, to help others avoid the mistakes I have made along the way, and delineate the distinct roles and contributions of the academic researchers and advocacy organizations in this partnership.

Scholarship and Advocacy

In October 1998, the Sentencing Project released a terrific report on Losing the Vote: The Impact of Felony Disenfranchisement Laws in the United States (Fellner and Mauer 1998). I had just embarked on an academic research project on this subject with the great Berkeley-trained political sociologist Jeff Manza, and we found this report to be a terrific up-to-date resource. I had met Jeff in May of that year, when he visited Minnesota to speak on U.S. politics and voting. I had not thought much about voting at the time, and he had not thought much about punishment. But when we met together and contemplated the sheer numbers of people that must be disenfranchised due to criminal records, we quickly hatched a plan to collaborate on a scholarly project. It was the academic equivalent of love at first sight.

Over the next decade, we wrote a book (Manza and Uggen 2006) and numerous articles on the origins and impact of felony voting restrictions in the United States. As we conducted this research — which involved archival work, historical demography, a national public opinion poll, surveys, and interviews with impacted individuals, and occasional meetings at the Lincoln Memorial and other national monuments — it became clear to us that these restrictions were unjust, often racist, and ineffective at preventing or controlling crime. Based on the research evidence we uncovered, we began advocating for voting rights restoration. In our publications and in our advocacy, we argued that restoring the vote would extend democracy, reduce racial disparity in ballot access, respond to clear public sentiment, accord with international standards, enhance public safety, serve reintegrative goals, and eliminate “unlawful voting” charges against people with conviction histories.

Body Blows and Knockouts

We emphasized these points in our books and articles, of course, and did our best to respond to journalists when they happened to call. Over time, we began to engage a bit more directly. For the past quarter century, I have been in frequent contact with attorneys, politicians, activists, and community members directly affected by disenfranchisement laws. Some were pursuing bold national changes to “knock out” the practice through litigation. In the wake of the 2000 election, for example, I served as an expert witness in unsuccessful efforts to challenge the constitutionality of the practice in cases such as Johnson v. Bush. I also tried to support those working on grassroots efforts for reform at the state level, often in legislatures but also in the courts and the executive branch. For example, I was an expert in Schroeder et al. vs. Minnesota Secretary of State, which challenged the constitutionality of a state ban for people on community supervision, and in local cases in which people on probation were charged with illegal voting. My work on these efforts has continued for 20 years, but progress has been haphazard and piecemeal. And it proved difficult (for me, at least) to respond quickly to requests for legislative testimony or new data analysis, especially when such assistance was urgently needed at times that conflicted with my day job as a teacher and researcher.

I also realized that I was “out of my lane,” lacking the skills to organize my own activities, much less lead a movement. I also lacked the grounded local perspective of the organizers themselves. As a sociologist, I could help provide some big-picture historical context and sometimes more granular data or sophisticated analysis, but I had no expert knowledge regarding the important strategic and ethical choices that advocates and leaders must make. Is it wise to push for total restoration of voting rights or to pursue an easier-to-pass bill that might restore rights for people on probation, but not for people in prison? Should change efforts be focused on litigation or shorter-term appeals to governors to invoke their pardon powers? As it turns out, there have been many successful pathways to reform, driven by the creative efforts of the real experts: the diverse activists and community members who do this work. If the research I conducted was to be of any use to these experts, I needed a partner who spoke their language.

Just the Numbers

Between 2020 and 2022, significant laws or policy changes expanding voting rights took effect in states across the country, including California, Connecticut, Iowa, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Virginia, and Washington. In 2023, we expect to add Minnesota and other states to this list. Sometimes people link our team’s research to these reform efforts, but only a lousy sociologist would claim credit for actually changing anything. We did not do that work and to suggest that we did is an affront to the actual changemakers — community organizers, justice-impacted people, activists, and politicians. All that we have done is provide some basic social facts regarding the laws and numbers and, perhaps, some ways to think about them in relation to other social institutions. Nevertheless, we have seen leaders referencing our reports and numbers during floor debates (including the wonky footnotes that our undergraduate assistants painstakingly fact-check each summer).

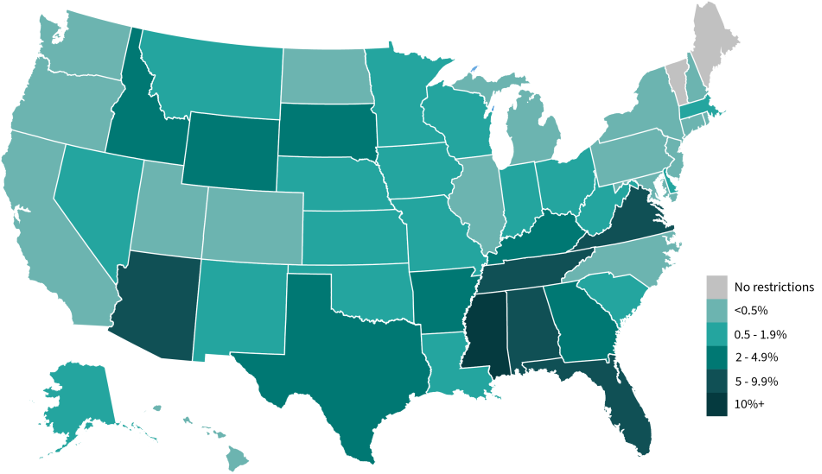

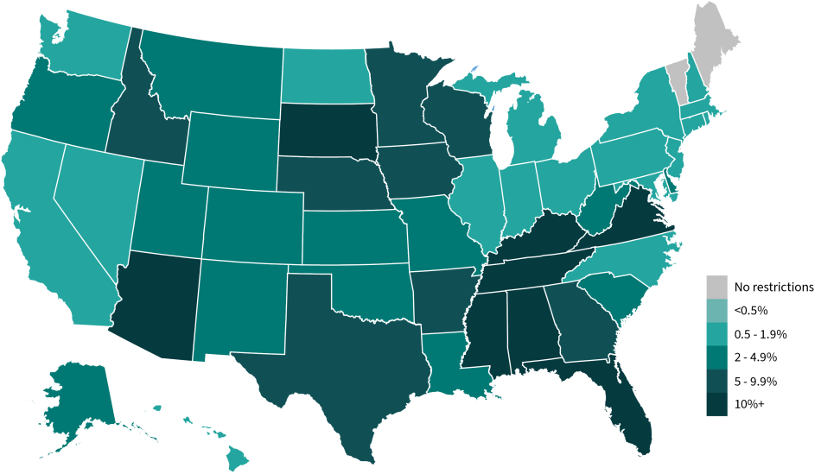

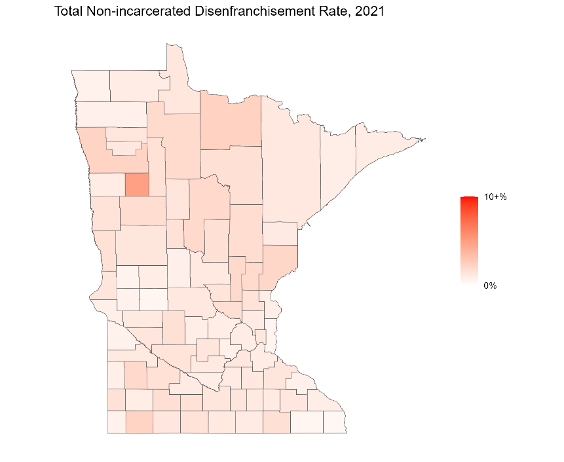

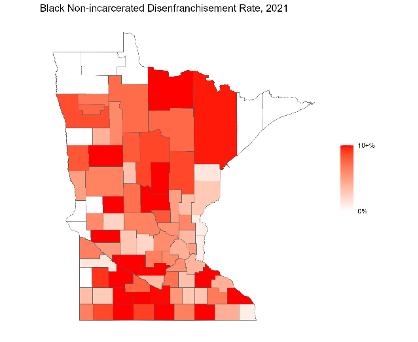

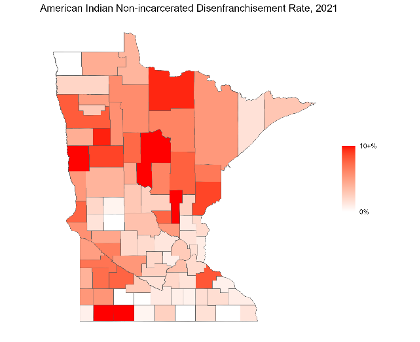

To give an example of such numbers, the figures below show our Locked Out 2022 state-by-state estimates. The first map shows the total percentage of the voting age population that cannot vote due to a felony conviction and the second shows the percentage of the Black voting age population that cannot vote due to a felony conviction.

In 2023, Ryan Larson and our team produced county-level maps groups at the request of Minnesota Justice Research Center and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Minnesota. These groups were interested in showing the geographic dispersion of disenfranchisement — that it wasn’t just an urban thing — as well as how the practice dilutes the vote of Black and Native Minnesotans.

Each scholarly product (and each presentation and press account of that product) represents a potential resource that could be mobilized by institutions and actors, but there are institutional barriers to realizing this potential. Often, relevant articles languish behind paywalls in relative obscurity. Brent Staples of the New York Times once wrote a brilliant op-ed on the racist history of disenfranchisement, drawing to some extent on our “racial threat” article in the American Journal of Sociology (Staples 2014). As he prepared it, however, I remember him calling to tell me how difficult it was for even New York Times journalists to gain access to many of our academic articles. Moreover, public and policy actors are typically most interested in up-to-the-minute numbers regarding the current situation, rather than our historical work – and even a 2-year-old article that uses 5-year-old data can seem hopelessly outdated in this context.

I began working with the Sentencing Project after some gentle nudging from its longtime director, Marc Mauer, a leading expert on sentencing policy, race, and the criminal legal system. Marc said that journalists and advocates needed up-to-date information about the number of people disenfranchised in their communities, the legal status of voting rights around the country, and the racial impact of voting restrictions at the state and national level.

It can be difficult for academic researchers, especially early-career scholars, to respond to such needs. First, researchers are judged on their scholarly publications and few journals are interested in publishing annual updates of basic social indicators. Public and policy organizations are keenly interested in disseminating such indicators, of course, especially regarding issues such as the gender wage gap, the child poverty rate, or (it turns out) the number and rate of people disenfranchised due to felony convictions. To date we have released at least four such reports with the Sentencing Project: in 2012, 2016, 2020, and 2022. These reports are not peer-reviewed, which leads to a second big problem for academic researchers. How do readers and advocates know that the technical details of the work are credible and well-executed?

We address these related problems by first publishing primary research articles (with methodological detail) in peer-reviewed academic journals such as American Sociological Review (2002) and Demography (2017). That way, readers can be sure that the methods behind the numbers have passed muster with other academics, even if each annual iteration has not. These reports are also vetted by the extremely knowledgeable and expert staff of the Sentencing Project, who rank among the smartest (and least BS-able reviewers) our team has ever encountered.

Expanding voting rights is a core strategic priority for the organization and our research team, which has included scholars such as Jeff Manza, Minnesota graduate alumni and now professors Sarah Shannon, Ryan Larson, Robert Stewart, and former undergraduate alumni such as Arleth Pulido-Nava and Angela Behrens. As their website notes, the Sentencing Project endeavors to “ensure universal suffrage for the millions of justice-involved citizens through national, state, and local campaign efforts focused on ending disenfranchisement and expanding voting rights to citizens with felony convictions and citizens detained in jails and youth justice facilities.” One might say it was the research team /advocacy organization equivalent of love at first sight. But successful partnerships are also founded on a material basis.

Financial Arrangements and Roles

Social science research is often funded by grants or fellowships, whereas nonprofit organizations often conduct research using their own in-house staff. The costs and overhead needed to prepare our reports are relatively modest, since we can build upon an existing base of research infrastructure (funded in part by earlier grants from the National Science Foundation and the Open Society Institute). We therefore use a hybrid arrangement in which the research team members bill hourly for their work, which is typically conducted over the summer. This is not pro bono work since we want to compensate team members for their time, especially those who are undergraduate and graduate students. Nevertheless, we try to minimize the costs and keep them to a fraction of what a stand-alone grant would cost. Because those of us on the research team support the goals and mission of the Sentencing Project, we are generally pleased to make an in-kind contribution of labor, and we are delighted when it reflects favorably on the organization.

Establishing a clear division of labor is critical in this sort of arrangement. In our case, the research team contributes scholarly expertise, data, analysis, writing, and methodology. The advocacy organization, in turn, contributes their considerable expertise, insight and pre-production critique, as well as design, layout, and infographics work and, critically, messaging and dissemination to their networks. In my experience, organizations like the Sentencing Project have far greater skills and resources to devote to such projects than individual researchers or their universities — and they also have more rich and expansive networks. As shown below, they can issue embargoed versions of the report to media prior to launch, which builds interest and allows journalists to develop stories around the report prior to launch. They can also track how much traction the report is getting, and they can organize events tailored to media and advocates around the country. Our reports typically garner attention from major media (e.g., the New York Times, NPR, The Hill) and the follow-up webinars for advocates and activists often attract hundreds of people well-positioned to make change happen (476 participants at one 2022 presentation).

Resolving Tensions

Not all research/advocacy partnerships are so harmonious, of course. In other settings I have seen how values or allegiances can clash. Sometimes advocacy organizations can push too hard for specific findings or “spin” results in ways that conflict with researchers’ professional and personal values. As Michael Buroway notes, one pathology of public sociology is the temptation to “pander and flatter its publics … thereby compromising professional and critical commitments” (2005:17). Conversely, researchers sometimes “spin” results in ways that gatekeep, stigmatize, or exploit communities. Given the history of such abuses, communities and organizations are understandably distrustful of collaborative relationships and researchers who put their personal or professional concerns above collaborative goals. In setting up any such arrangement with new partners, I try to engage in clear communication about shared goals while also protecting the basic integrity of the research being conducted. In an experimental audit study conducted with a community partner, for example, the research staff was solely responsible for the randomization process. In this study, the researchers were also housed in an office next door to the community partner’s offices, so that we were in close proximity but independent of the organization’s day-to-day outreach activities. The resulting research, which played a role in changing state law regarding the questions employers can ask on job applications, would have been far less valuable to advocates if it had been perceived as sloppy or rigged to yield a particular talking point. I have never had such concerns in working with the Sentencing Project. In fact, they tend to ask considerably more pointed questions about the findings that support their policy positions, adding margin notes to our drafts that demand more evidence or citations.

Regarding tensions, I should also be honest about my own failings as a public sociologist, particularly regarding the timely completion of reports and deliverables. The academic calendar is generally more forgiving than the policy and public calendar, and academic researchers are generally freer to indulge their perfectionism. Just as we sometimes struggle to let go of our academic writing and submit it for publication, I often struggle to let go of a public report in time for it to be of any use to the advocates. As a friend once said, “I don’t think they’re going to delay the election while you finish your pre-election report, Chris.”

More generally, though, working with knowledgeable community partners raises the game of researchers and improves the quality of their work. Like good ethnographers, advocacy organizations (and journalists as well) often have their ears to the ground. This means they will likely learn more quickly how courts are currently interpreting a North Carolina decision or how the unified prison and jail system in Connecticut might affect estimates of the disenfranchised population among people who are currently incarcerated. They also provide wicked-good editing and critique, providing far more scrutiny and attention to detail than journal editors or book publishers. Such organizations are also skilled in crafting impactful executive summaries and preparing graphics that resonate and “travel well” with different audiences. As importantly, their direct connection to local and national media representatives and activists gives the resulting reports the best opportunity to be read and put to good use.

Core Trust

In short, a well-matched team of researchers and advocates who trust one another can accomplish a great deal together. Over the past two decades, my team has developed a core of trust and commitment with the Sentencing Project and a real appreciation for their knowledge and expertise. This core trust may have been built on individual relationships, but it now extends to a much broader set of actors on each side. And it has survived and thrived with transitions in executive leadership (from Marc Mauer to Amy Fettig at the Sentencing Project) and research team members (as scholars such as Ryan Larson and Rob Stewart have joined the Minnesota research team). As in other relationships, this trust is built on a foundation of mutual respect. For my part it means being a bit humbler about my own expertise and a bit more ambitious about the collective goals we can accomplish together.

As Robert Smith pointed out in his 2022 Eastern Sociological Society presidential address, the long-term viability of publicly engaged sociology efforts often depends on the quality of relationships with external partners (see also Hartmann et al. 2023). And whether and how social science research is used by policy actors depends as much on the quality of relationships as on the quality of research (see, e.g., Gamoran 2018). This essay has offered a simple case study of a longstanding and effective relationship between Minnesota researchers, an institutional partner in the Sentencing Project, and a diverse set of publics.

References

Behrens, Angela, Christopher Uggen, and Jeff Manza. 2003. “Ballot Manipulation and the ‘Menace of Negro Domination’: Racial Threat and Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States, 1850-2002.” American Journal of Sociology 109:559-60.

Burawoy, Michael. 2005. “For Public Sociology.” American Sociological Review 70:4–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240507000102

Fellner, Jamie and Marc Mauer. 1998. Losing the Vote: The Impact of Felony Disenfranchisement Laws in the United States. Washington, DC: Sentencing Project.

Gamoran, Adam. 2018. “The Future of Higher Education Is Social Impact.” Stanford Social Innovation Review. May 18.

Hartmann, Douglas, Christopher Uggen, and Mahala Miller. 2023. “There’s Research on That: Translating and Sharing Sociology for Public Audiences.” Forthcoming in Sociological Forum.

Manza, Jeff and Christopher Uggen. 2006, 2008.Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Shannon, Sarah, Christopher Uggen, Jason Schnittker, Michael Massoglia, Melissa Thompson, and Sara Wakefield. 2017. “The Growth, Scope, and Spatial Distribution of People with Felony Records in the United States, 1948-2010.” Demography 54:1795-1818.

Smith, Robert. C. 2022. “Advancing Publicly Engaged Sociology.” Sociological Forum 37: 4:926-950.

Staples, Brent. 2014. “The Racist Origins of Felon Disenfranchisement.” New York Times. November 14.

Sullivan, Caroline. 2023. “Nearly 70 Bills Introduced To Restore Voting Rights After Felony Conviction.” Democracy Docket. February 23.

Uggen, Christopher, Ryan Larson, Sarah Shannon, and Robert Stewart. 2022. Locked Out 2022: Estimates of People Denied Voting Rights Due to a Felony Conviction. Washington, DC: Sentencing Project.

Uggen, Christopher, and Jeff Manza. 2002. “Democratic Contraction? The Political Consequences of Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States.” American Sociological Review67:777-803.

Christopher Uggen is a Regents Professor in Sociology, Law, and Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota and co-editor and publisher of TheSocietyPages.org. He studies crime, law, and inequality, firm in the belief that sound research can help build a more just and peaceful world. His books include Incarceration and Health (Oxford, 2022) and Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy (Oxford, 2006). Uggen’s current projects examine voting rights, Scandinavian justice, and monetary sanctions. He is a fellow of the American Society of Criminology and a recent Vice President of the American Sociological Association.