Una Escuela Llamada América: Documentary film and photography as ethnographic tools for reflexive social research

Antonia Mardones Marshall, Roberto Velásquez Quiroz, Pablo Mardones Charlone and María Paz Espinosa Peña

Abstract

How can documentary strategies advance sociological insights beyond academia? This photo-essay analyzes the process of producing the documentary film “Una Escuela llamada América” with immigrant children in Arica – the northernmost city in North Chile, only 20 kilometers south from the frontier with Peru. We reflect upon the documentary’s production and its relationship with social research in order to show how visual narratives can serve public debates. The photographs included in this work document different stages of the process of narrative-making. Ultimately, these visual sources highlight the agency of the film’s protagonists in framing their own stories in the collective assembling of the audiovisual pieces. Film directors and participants are thus crucial agents in the effort of producing this piece of visual sociology.

Introduction

This work explores international migration through the lens of documentary film and photography to expand public sociology to some of the most unseen issues related to immigrants’ experiences and how they are perceived by receiving societies. Inspired by recent development in social sciences, primarily in anthropology and sociology, we craft documentary-making as an ethnographic exercise. In other terms, images, words, and sounds are bound to connect axes of observation and reflection via camera framing. In our view, this dynamic and dialectical process involving producers, actors, and spectators makes observable social interaction more complex and richer. Ethnographic visual resources thus play a crucial role in the production of knowledge for the communities involved (Mardones and Riffo, 2018).

While searching theoretical tools for enhancing our audiovisual approach, we found Pierre Bourdieu, Margaret Mead, and Jean Rouch’s groundbreaking use of photography and film to be an outstanding source of inspiration (Bourdieu,1991; Mead, 1960; Rouch, 1975). The figurative image of the camera lens capturing so-called “objective realities” with its “pure mechanical gaze” was a common topic of debate since the 1970s (Dubois, 2021). At this effervescent period for scholars across the globe, photography and documentary film production were subject of criticism in philosophical aesthetics (from art to literary theory, see Barthes, 1980; Sontag, 1977), history (from art history to social history; see Krauss, 1984; Freund, 1979), anthropology (from material approaches to visual ethnographies, see Collier & Collier, 1986; Gell, 1990), and sociology (from poststructural to phenomenological approaches, see Bourdieu, 1991; Goffman, 1971). The main issue was debunking the idea of naive realism in camera-based records, which saw the photographic representation of reality as the most “realistic” form of visual evidence. Contrary to the positivist tradition in the photographic practice, the new program for social scientists focused on “the photographic image as a privileged opportunity to employ an original method designed to apprehend with a total comprehension” (Bourdieu, 1991, p.7) 1) the objective regularities of behavior (e.i. social contexts), and 2) the subjective experience of that behavior (e.i. both the photographer and viewer’s social understanding of the photographic and/or documentary experience).

In anthropology, it was a moment for researchers to look at visual evidence in terms of reflexive strategies. Concerned by the lack of sources to analyze themselves as research subjects when at fieldwork, a new generation of scholars delved into documentary traditions to harness the perplexities of recording socialization. The result was a flourishing field of ethnographic evidence that due to its audiovisual nature allowed an increasing number of communities to access social science’s investigation. In fact, reflexivity became a relevant milestone for the rise of interpretative, constructivist, and critical approaches led by the so-called “ontological turn.” It was a period for promoting the production of more dialogic and collaborative research, committed with local communities while engaging with active social transformation.

The ethnographic work involved in our documentary-making process confronted us with empirical conditions that challenged these notions of camera-based methods, reflexivity, and collaborative research. In the first moment, encountering others within the craft of audiovisual production certainly brought the public dimension of social sciences closer to our attention. The main characters in our film, immigrant children and their families, increasingly engaged in our research not only using their own voices to tell their stories but also partaking in crucial narrative decisions for the documentary film – such as where and what to display in order to better show their identities. Across iterative exposure to this dynamic, we thus forged an affective relationship with the protagonists, which allowed us to carry out a committed and extensive fieldwork sustained over mutual trust. This strategy also led us to take a political stance around the purpose of the production of knowledge (Hale, 2004) and to orientate our research in relation to previously agreed commitments.

The product of our fieldwork, the film itself, took us to a second moment of engagement with the public. We found the audiovisual language to be much more fluent and accessible than written text to broad audiences – even considering heterogeneous composition within different levels of educational and economic background. Furthermore, the documentary film was not only shared proudly by the protagonists with their families and friends, perhaps more meaningful for participants, it was also broadcasted in local and international festivals across the globe. Displaying Una Escuela Llamada América [“A School Called America”] in world-viewed spaces, such as the Cinemaking International Film Festival held in Bangladesh where the documentary received an Honorable Mention Award, and other local scenes, such as the Native Movies Festival held in Arica where the film was awarded the Best Local Film award, gave the community a sense of visibility that empowered their immigrant identities. It also gave the protagonist children a new form of speech, a visual one, in which the aesthetic dimension they deploy results in a powerful voice to resist hate discourse, xenophobia, and ethnic discrimination in an era of increasing race-oriented violence in the country.

Ultimately, this documentary production has been a matter of circulation and reciprocity. It has been used in pedagogical contexts, from kindergarten to graduate university classrooms, as well as in workshops for teachers and public functionaries that engage on a daily basis with immigrant populations. In his 2004 ASA presidential address, Michael Burawoy highlighted the relevance of teaching to public sociology, as “students are our first public for they carry sociology into all walks of life” (Burawoy, 2004). From this perspective, the pedagogical value of documentary products is immeasurable as a film can be reproduced simultaneously in several venues and classrooms around the world, feeding processes of intercultural learning in a way that would hardly be possible through more conventional teaching formats.

Thoughts on Documentary Making, Photography, and Ethnography in Arica

Photo 1: Panoramic view of the city’s historical urban center, “morro,” and port. For locals, visitors, and anyone paying attention to the sightseen, it becomes clear the extent to which the city’s aesthetics (perceived as a place of encounter for desert and ocean to depart from inhospitality to grant shelter to human life) remains at the core of Arica’s experienced identity. A closer look at the picture shows how Andean carnival troupes parade through one of Arica’s main streets, giving us a glimpse of the city’s multicultural composition. Source: Una Escuela Llamada América project archive.

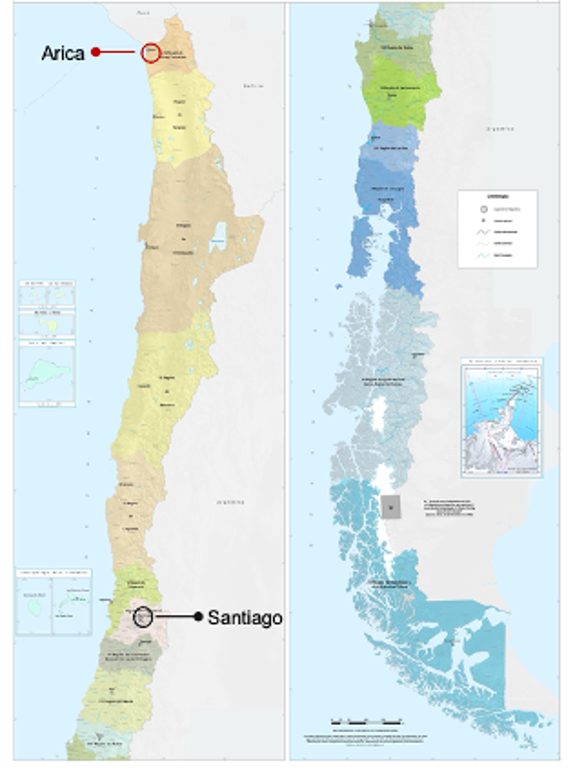

Our ethnographic research and film production was staged at Arica, popularly known by locals as “the city of the eternal spring” and the northernmost urban center in Chile (figure 1). This city, once Peruvian, only came to be under Chilean administration after the Pacific War (1879-1883), in which Chile indexed large continental territories from both Peru and Bolivia. Probably the most contentious geopolitical event in nineteenth-century Chile, Arica’s historical occupation settled the foundation for frontier and transnational identities to flourish across time. Beyond state narratives, the city’s beauty and bounty have remained cherished, seen, and felt by its lively and heterogenous population up to this day. An oasis that shines with a pluricultural atmosphere at the edge of the Pacific Ocean and Atacama’s Desert, Arica grew in our minds as an interesting scenario where to further explore relevant issues on migration and frontier identities.

Figure 1. Chile’s administrative regions and regional capitals. Source: Chilean National Congress Library (https://www.bcn.cl/)

On the one hand, as our interest in the field developed from previous research experience at Arica’s frontier, the relationship between migration and ethnicity remained at the core of our attention. Our close observation of Afrodescendant and Indigenous communities remained in the background of our intellectual and affective connection with this mesmerizing landscape. On the other, our previous experiences with documentary film production in 2009 had given us a closer look at immigrant infancy and childhood in Santiago. In this way, Una Escuela Llamada América was imagined, discussed, filmed, and produced to help us explore the interwoven relationship between migration, frontier, and childhood. Our main objective was ultimately tracing integration and recognition dynamics deployed in two different nationally bounded contexts: center/capital and periphery/frontier.

Photo 2: Everyday scene from Escuela América’s classrooms, an educational center in Arica with an inclusive perspective towards migration and pluricultural education. The picture was taken during an Aymara class – a language spoken by Indigenous Andean peoples in Peru, Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile. Source: Una Escuela Llamada América project archive.

The question of observation and recording strategies seemed hard to frame for our crew prior to finding Escuela America – a lively small world. This school community made us observe Arica’s diverse nature from a different angle, that of children sharing narratives of identity and belonging. The school is a public K-8 establishment with one of the highest proportions of immigrant children in the urban center. Furthermore, its heterogeneous composition reflects upon the school’s active policy and regulation that strengthens an inclusive pedagogical environment, nurtured with institutional respect to pluralistic community values. When we started working on this project in 2019, we quickly learned about the potential of focusing our documentary on the way in which the lives of these children reveal the quest for recognition in Arica. They seemed to effortlessly engage in conversation with us, especially when interactions included audiovisual material or a camera recording session. We felt profoundly compelled by their disposition to share their views through the playful practice of seeing and being seen by the camera lens.

Photo 3: National and immigrant students at Escuela América wearing traditional dresses and costumes in celebration of Chile’s National Independence Day or “18 de Septiembre.” Source: Una Escuela Llamada América project archive.

As we engaged in documentary film preparations, we established close contact with the school principal and other members of the school community. Conversations resulted in a combination of enthusiasm and curiosity for our project, which granted us the possibility of learning from the children’s experiences while filming at school. As explained to the school board, our initial goal was to include an extensive “classroom ethnography” to observe and portray the internal school dynamics related to the high presence of immigrant children. Still, there was a profound sense of enchantment by the metaphoric space we found: América. In many respects, we found that the word America, as used for naming the school but also the continental diversity of the students, was both captivating and worth narrating.

After confirming the school as our leading research site and production set, we began the journey of finding potential protagonists: students with histories and voices of their own. Fortunately, we navigated this challenge with the valuable help of teachers and other community members who have known children for several years. Specific characteristics were of particular importance for our project: we intended to represent children’s views considering the diversity of gender, nationalities, ethnicity, and age. As previously discussed by crew members, we felt it was essential to record narratives of both boys and girls, with different migration experiences depending on country of origin, and that they were old enough to elaborate discourse around integration experiences. Our only reservation was whether potential protagonists were old enough to have become less spontaneous, so to speak. This was essential for establishing an affective space to explore otherwise normative discourses of state, territories, and political identities.

After interacting with candidates, we decided to focus our work on four immigrant children between 10 and 14 years old. Two of them were girls: Deyna from Bolivia and Zaira from Colombia; the other two were boys, Joaquin from Peru and Ricardo from Venezuela. They represented the diverse cultural roots of immigrants in Arica. Unfortunately, Zaira went back with her family to her home country during the production of the documentary, and we could not include her in the film. However, we continued working with the remaining three students, who were additionally actively engaged with the student board and advocating for their peers in the larger school community.

Photo 4: Dilan, our Chilean protagonist, looks at the camera with profound pride and joy from being filmed by our crew in front of his classmates. Source: Una Escuela Llamada América project archive.

While scripting the documentary film, we noticed the importance of incorporating the perspective of a Chilean student to grasp inclusion dynamics from a local perspective. Dilan’s incorporation into the film allowed us to explore a vision of migration from the receiving end. We intended to enhance closer interactions between Chilean and immigrant students in Arica. Furthermore, Dilan’s narrative brought elements of intra-national migration to the scene since his grandmother, and most crucial parental figure, was a migrant herself. She incarnated the stories of families that followed south-north migration patterns after the return of democracy in 1990 (Rodríguez and González, 2006).

The time needed to produce a documentary film starring children implied deepening into a relationship based on trust between the crew, children, and their families. Our protagonists’ caretakers had to develop confidence that their children would be safe with us during the entire film recording. To achieve this trusted bond, we invested our time in getting to know each family closely to incorporate their vision around their children’s experiences regarding the topics we touched upon in our project. The documentary methodology we framed was focused on recording at least one individual and extensive interview with each student, in addition to a group interview with their families. This strategy allowed us to explore both the student’s history, perspective, and points of view, in conversation with those stories and images brought to the scene by their families. In doing so, we were able to reconstruct a more detailed narrative of these families, how they had arrived in Arica, and how their migration experiences had shaped their perception of the country.

Photo 5. Family scene portraying Deyna’s household. During the shooting, her grandmother and father had expressed profound pride in Deyna’s school leadership and intellectual curiosity. Source: Una Escuela Llamada América project archive.

While individual interviews sought to provide children with space to express their ideas without having to confront the authoritative voice of adult caretakers, family interviews remained central to the film’s primary goal of portraying the children’s bounded realities. At this stage, a significant challenge was negotiating our own research goals with the children and families’ expectations of what the documentary should display, or what aspects of their stories should be highlighted in favor of others.

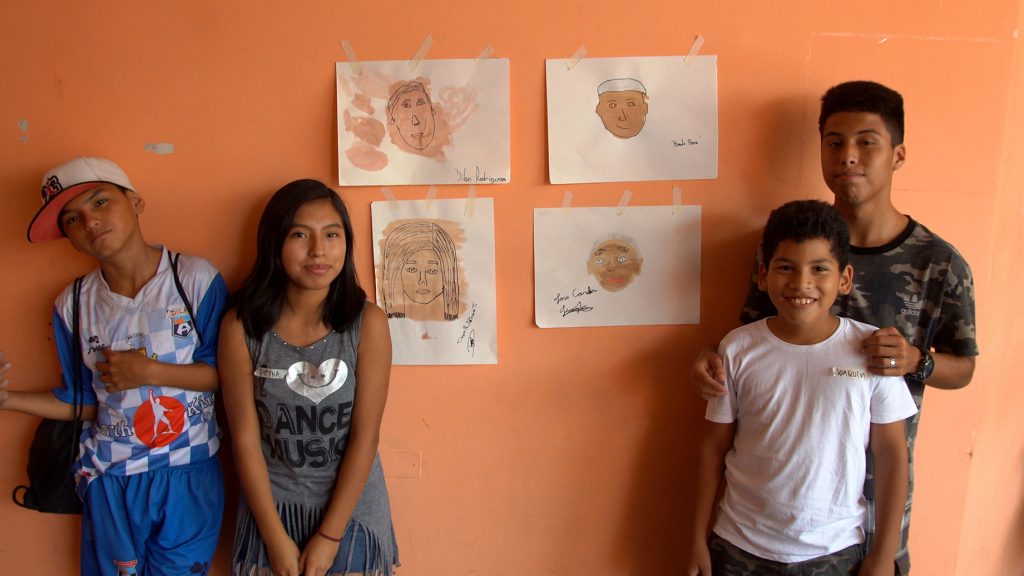

As much trust was crucial for developing a fluent dialogue between producers, children, and their families, allowing our protagonists to get to know each other was equally crucial so they could spontaneously exchange their different experiences and viewpoints. We helped them build a safe space for sharing their opinions while at the beach or through previously planned interactive workshops. The “color of the skin” workshop was an especially intimate and moving space where all of them were given art supplies to make self-portraits and represent themselves as they wanted to be seen, while challenging myths of what does “skin color” means. This workshop was led by a guest psychologist who is an active member of a local organization in the city of Antofagasta that focuses on anti-racism and intercultural education. We asked Arica’s Public Municipal Library to host our initiative, which they cordially accepted and ended up being a fundamental setting in the definitive film script.

Photo 6: Final results of the “color of the skin” workshop, carried out at Arica’s Public Municipal Library, where each of the students told their own origin story represented in a self-portrait. Source: Una Escuela Llamada América project archive.

Since we thought of non-written discourses as a better choice for delving into the student’s imageries, we heavily relied on workshops and activities that incorporated aesthetic experiences such as exploring self-identity through playing music, dancing, or painting. It is worth noticing that some of the richest testimonies came as reflections around these aesthetically oriented interactions.

Reflexive Social Research

As in any ethnographic research, documentary film production implies a certain degree of contingency – frequently unexpected events can affect production, script, and other relevant components. In our case, first an extended national-level teachers’ strike and then the Chilean 2019 social uprising [“Estallido Social”] had made schools close, including public facilities in Arica. Since we intended to focus on the classroom, a closed school did not help our endeavors. The nation-wide social uprising however gave us an opportunity to explore film participants’ political views as they spontaneously referred to what they perceived was causing such social unrest and compared these events to previous experiences in their home countries.

As filming at the school was no longer possible, we decided to focus on children’s integration in other spaces, including their hobbies and after-school activities of choice. This turn of events ultimately allowed us to portray more deeply intra-family relationships. In the case of Joaquín, the main activity he did outside of school was playing the drums for a carnival band in which he participates with his mother – a skillful dancer. To stimulate him to talk about how he came to play drums and how this helped his integration into Chilean society, we contacted a guest luthier in Arica, Francisco Piñones. Thanks to Francisco’s generosity, we could spend an afternoon with Joaquín, learning and observing how traditional Afro-Chilean drums are crafted in Arica. Joaquín was so excited about this experience that he felt compelled to share part of his vision on music: he had decided thanks to this experience that he would grow up to become an “instrument maker” himself. The afternoon finished with Joaquín and Francisco playing some music together, which we included in the film with drum-making scenes.

Photo 7: Joaquín and Francisco Piñones discussing how different materials can produce an interesting repertoire of tones and shapes that are proper of Arica’s drum-making tradition. Source: Una Escuela Llamada América project archive.

We felt very interested in seeing the children’s narrative from their perspective. Understanding the power of images was crucial during our early readings, so on that note, we asked them to share family portraits and photographs when possible. Interviews and recording sessions gravitating around family albums helped us build the affective bridge to explore topics of ethnicity, ancestry, kinship, and future — the resulting sequences reflected upon intimate spaces of hope, visions of integration, and community belonging.

Photo 8: Ricardo showing in his phone a picture of him playing soccer as a kid in Venezuela, which opened conversations about what it meant for him to leave his country to migrate together with his family to Chile and how his passion for soccer followed him through this migratory quest. Source: Una Escuela Llamada América project archive.

After spending time with families, we proceeded to do individual interviews with each of the students. All the previous time spent on trust-building was essential so that the children felt confident (and not threatened) by the presence of a camera. Being without their families also allowed them to share the topics they felt were more critical without dealing with other family members and their visions. To engage with them in a collaborative environment, we left time from interviews to explain how film production worked, the craft of camera-based materials, and the different devices implied in sound and light productions. This moment of retribution and encounter made the documentary scenes lively and profoundly personal.

Photo 9: Joaquín, with two of the film directors, learning how to use a camara. Source: Una Escuela Llamada América project archive.

Epilogue

The results of research within the social sciences are almost exclusively presented to the public through books and academic articles. In sociology particularly other non-traditional formats are frequently disregarded by orthodox scholars who do not consider them to be properly “sociological”. Throughout these pages, filled with photographs and stories, we have carefully documented our journey towards documentary film production to argue about the relevance of images and narratives in reaching the public, in a double sense.

Our main focus has remained on documentary-making as an ethnographic exercise, which means we have internalized the ethnographic practice through the enactment of the cinematic language and its resources. However, what remains particular to our lived experiences is the conclusion that crafting Una Escuela Llamada América was mostly about finding the right bridges to connect and get involved both producers and participants. Such connections proved crucial in the work of portraying Deyna, Ricardo, Joaquín, and Dilan’s stories of migration and identity construction. Ultimately, it is on this note that we believe community-oriented documentary strategies can uncover unseen aspects of immigrants’ experiences while allowing them to co-participate in the production of sociological knowledge.

Photo 10: Una Escuela Llamada América being shown in a school in the context of the 2021 School Festival Cine Éjate, in Calbuco, Región de Los Lagos, November, 2021. Source: Gabriel Montiel, audiovisual producer

Our engagement with the public did not end with the production of the documentary. After post-production, the social life of the film has integrated a large chain of exchange in documentary film screenings, festivals, and conferences. Once we received the first set of DVD copies we immediately sent them to our film protagonists, their families, project collaborators, local authorities, and the broader community. This included schools, cultural centers, and other spaces in which we hope the film will be used for pedagogical purposes in the future. This form of reciprocity with the community is not frequently included in cinematographic projects. Still, we believe as social scientists that it is part of our responsibility to reciprocate to the same extent the immigrant students and their families helped us see Arica and its multiple worlds. Sharing copies and organizing screenings of Una Escuela Llamada América are some of the many forms we are convinced documentary films can positively impact the communities we encounter, both empowering immigrant communities and constructing bridges of empathy and understanding with non-immigrant audiences. Under the realization of the limited impact that our written work has outside of academic contexts, we believe that audiovisual formats have the potential of constituting a powerful tool for enhancing critical thinking and social awareness within the communities we engage with. Finally, we hope that this example can serve social scientists and other peers in the different fields gravitating around audiovisual methodologies to navigate the work of bringing academic discussions closer, and more meaningful, to non-academic communities.

Figure 2: Poster for Documentary Una Escuela Llamada America. Source: Art and design by Memo Rodriguez.

References

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang Editors, 1981.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Photography. A Middlebrow Art. California: Stanford University Press, 1991.

Burawoy, Michael. American Sociological Association Presidential address: For public sociology. American Sociological Review, 2005, Vol. 70, Issue 1, 4-28. 2004.

Collier, John & Collier, Malcom. Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method. Albuquerque: New Mexico University Press, 1986.

Dubois, Philippe. Photographie & Cinéma. De la différence à l’indistinction. Paris: MIMESIS. 2021.

Freund, Gisële. Photographie und Gesellschaft. Hamburg: Rowohlt Tb., 1979.

Gell, Alfred. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Goffman, Ervin. Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order. New York: Basic Books, 1971.

Hale, Charles. Reflexiones hacia la Práctica de una Investigación Descolonizada. Managua: Universidad de Texas-Austin, 2004.

Krauss, Rosalind. “A Note on Photography and the Simulacral.” October, vol. 31, The MIT Press, 1984, pp. 49–68, https://doi.org/10.2307/778356.

Mardones, Pablo & Rodrigo Riffo. ¿Y para dónde vamos? Antropología Audiovisual latinoamericana. Madrid: Editorial Académica Española, 2018.

Mead, Margaret. Work, leisure, and creativity. Daedalus, 89(1), 13-23, 1960.

Rodríguez, J. and González, D. “Redistribución de la población y migración interna en Chile: continuidad y cambio según los últimos cuatro censos nacionales de población y vivienda”. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 35, p. 7-28, 2006.

Rouch, Jean. “The camera and the man”. P. Hockings (Ed.), Principles of visual anthropology, 79-98. La Haya: Mounton, 1975.

Sontag, Susan. On photography. New York: Rossetta Books, 1977.

The production of the documentary portrayed in this essay was possible thanks to the funds obtained with the project “Una escuela llamada América”, from the Regional Fund – Immigrant Cultures Category, of the Chilean Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes. Documentary trailer available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vhpUL7Kb8Lk. To ask for permission to use the complete film for community-based projects or pedagogical purposes, please email Antonia Mardones at mardones_antonia@berkeley.edu and she will provide you with an access link.