Union Democracy, Student Labor, and the Fight for Public Education

Shannon Ikebe

Radical social movement unionism among UC academic workers represented by the UAW provides a model for connecting labor struggles with the fight to defend public goods.

Grad student workers at UC Berkeley strike over unfair labor practices. Photo credit: Jonathan Smucker

“We love our union because it is a step towards abolishing heteropatriarchal capitalism.”

—Academic Worker Activists’ Slogan, May Day 2014

In recent years, cutbacks at California’s premier public university system, the University of California (UC), have dealt a devastating blow to students and UC workers, spawning a fierce resistance struggle across the state. As students have joined together to fight tuition hikes, degraded learning conditions, and undemocratic decision making, labor unions representing UC workers have played an important role. In particular, radical social movement unionism among academic workers represented by the UAW (United Auto Workers) provides a model for connecting labor struggles with the fight to defend public goods.[1] We contend that the increasing proletarianization of academic labor has the potential to break down the age-old separation on the Left between “intellectuals” and “workers” as academic workers gain a greater degree of class-consciousness. The persistence of the Left in academia in times of right-wing dominance has contributed to the radical character of academic workers’ movements, and offers the prospect of revitalizing militant grassroots labor movements in the US and of defending public higher education as a social right.

The Crisis of Public Education in the Golden State

California’s public university system is one of the nation’s largest and most prestigious, with a long history of radical activism. The top tier is the UC system, serving 233,000 students across ten campuses. While the famed California Master Plan for Higher Education declared in 1960 that “the University of California shall be tuition free to all residents of the state,”[2] at the height of the American welfare state, the principle of free education was gradually eroded by the neoliberal offensive. In the 2000s, the UC Regents moved to further privatize the university rapidly and drastically. Tuition, which was less than $3,000 as recently as in 2001, has quadrupled within a decade.[3] The increased tuition was used as collateral for construction bonds on campuses and to pay the salaries of an ever-expanding legion of senior managers, the number of which in 2011 exceeded the number of regular faculty for the first time.[4] The capitalist crisis that began in 2007 provided a pretext to drastically reduce state funding for public education, and by 2011, the tuition revenue for the UC system exceeded public funding, despite being a “public” university.[5] The announcement of a 32% fee hike in 2009 and proposed cuts in state funding for higher education by more than a billion dollars triggered a mass student movement, which was the largest in many years. Sparked by the Wheeler Hall occupation at UC Berkeley in the fall of 2009, mass rallies for public education took place across the state, on UC campuses, community colleges and public high schools.[6]

The neoliberal assault on public education has also had a detrimental effect on livelihoods of academic student-workers (ASWs). While pursuing higher education is a privilege, in the absence of a living wage, many ASWs survive through crippling debt, second and third jobs, food stamps, and foregoing basic necessities of life such as adequate housing and necessary health care procedures.[7] The average graduate school debt for Ph.D. students in humanities and social sciences exceeds $20,000, in addition to any pre-existing debt.[8] Furthermore, the prospect of paying off such heavy debt through an academic career is remote as tenure-track positions becoming ever more scarce due to the adjunctification of academia; by 2011, more than 40% of instructors in higher education were adjuncts, and well over half of new hires were for part-time positions without basic benefits.[9] The assumption that the majority of graduate students come from backgrounds with an independent source of wealth gives rise to the perverse logic that people who perform necessary labor should have to rely on personal sources of income in order to do that work, denying the existence of the very system of low-wage exploitation that underlies modern university education. Furthermore, the poverty of our wages and working conditions creates clear barriers to pursuing higher education for those who lack external resources and must fund their education through their labor, reinforcing hierarchies of race, gender and class. Is academia to become a dilettante pursuit for members of the ruling class, who have the time and money to pursue a PhD for fun?

At the University of California, the ASWs’ labor union, UAW Local 2865, played a crucial role in fighting against the capitalist offensive against public higher education. The union represents more than 13,000 teaching assistants, readers and tutors from all 9 teaching campuses of the University of California system, making it the largest ASW union in the United States. While the union was rendered inactive for many years by bureaucratic control, a new movement of radical student-workers organized as the Academic Workers for a Democratic Union (AWDU) caucus took power in the spring of 2011, creating a new relationship between labor and the student movement in CA. The union began to organize in solidarity with the student anti-austerity movement and place quality of education and access demands at the center of its contract fight, making the union a potent force for fighting cutbacks. In this article we elaborate the potential of radical labor organizing among graduate students for the preservation of the public university.

A Brief History of Graduate Student Unionism

For many decades, academic student-workers (ASWs) have comprised around 20% of the entire teaching workforce in American universities.[10] Tens of thousands of graduate students teach college courses to make a living,[11] However, it is our very status as workers that has been disputed, as university management has always sought to deny it for union-busting purposes. Their logic goes that because we are students, therefore we are not workers; indeed, the National Labor Relations Board officially accepted the logic of an inherent contradiction between the statuses as a worker and as a student as the basis to deny grad student-workers at private universities the right to unionize.[12] On these grounds, the UC administration fought against unionization of graduate student instructors for three decades. UC graduate students first made an effort to unionize in the 1960s; at UC Berkeley, the Free Speech Movement directly inspired one of the first efforts in the country for ASWs to unionize.[13] ASWs won union recognition in the 1960s at some campuses, such as the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the City University of New York; however, most efforts fizzled out in the first wave. At the UCs, another wave of struggle began in 1983, when the majority of grad students at Berkeley signed union cards, and campaigns at many other UC campuses followed with a majority sign-up within the next few years. After repeated strikes over many years on multiple UC campuses throughout the 1990s, including a grading strike on all 8 campuses at the end of 1998, the Public Employee Review Board (PERB, an equivalent of the NLRB for California public workers) finally recognized ASWs as “workers” in 1999, forcing UC management to recognize the union.

Despite the decades of struggle and militant tactics that went into getting union recognition, in 2009 UAW 2865 was not a force to defend public education, or even to fight for a good contract for its own members. While organization and a dedicated cadre of activists is important, bureaucratic control can hinder mobilization, as we have repeatedly seen in the history of the American labor movement. The UAW is notorious for its bureaucratic domination and lack of internal democracy, having been controlled by the tight-knit Administrative Caucus[14] for many decades, which established a cordial relationship with auto companies and the Democratic Party. Following its long-standing pattern of crushing militant rank-and-file workers’ movements—including by physically assaulting picketing workers on a wildcat strike—and negotiating ever-worsening concessionary contracts, the UAW bureaucracy began attempts to control grassroots organizing efforts by imposing their organizers at the expense of democratic organizing by activists, and even invaded activists’ homes to steal union records to prevent them from autonomously organizing.[15] Such tactics disillusioned many activists, creating apathy and ambivalence. The union had difficulties filling officer positions, its meetings were sparsely attended, and its affairs were often effectively run by non-elected UAW International staff and their hand-picked lieutenants.[16] Those who served loyally in the local Admin Caucus were sometimes given a job in the UAW hierarchy after leaving graduate school. The purge of the American Left from labor unions during the McCarthy era paved the way for repression by conservative labor bureaucracies, which drastically weakened resistance to assaults from neoliberal capital.[17] However, as the Left has increasingly found its home within academia and academic workers began to unionize, academic unions—in particular within the UAW—have become the frontline of tension between the politics of radical student movements and of bureaucratic control.

However, the difficulty of labor organizing among academic student-workers is not limited to management hostility and union bureaucracy; it is also a question of class-consciousness among the workers ourselves. As noted above, universities have not been unsuccessful in asserting that student-workers are not workers. Teaching assistants at private universities and research assistants at both public and private universities in many states are still barred from exercising their labor rights because the law says they are not workers. Even when student-workers have the right to unionize and are represented by a union, our experiences have shown that overcoming our fellow academic student-workers’ inclination to think of themselves primarily as students rather than workers is a major barrier to organizing. As Marc Bousquet puts it, the difference between employing non-students rather than students to perform labor is the difference between “persons who claim citizenship in the present, not citizenship in the future.”[18] Persons who only claim citizenship in the future are cheaper to employ in the present, at least from the employer’s perspective.[19] Indeed, in today’s late capitalist economy characterized by low-wage service employment, precarity, part-time labor, and the “sharing economy,” the question of who thinks of themselves as workers is crucial to low-wage labor regimes in a wide variety of industries. In particular, academic student-workers have had to overcome the pervasive yet misleading conception of ourselves as uniquely privileged and able to “afford” to work low-wage jobs for significant portions of our lives, and thus lacking the deprivation to justify militant union struggles and strong identification as workers. The question of who is a worker and the struggle to develop class-consciousness among workers who might initially see their labor as temporary and incidental to their identities may prove to be some of the most important labor struggles in the current economy.

Academic Workers for a Democratic Union (AWDU): From a Business Union Model to the Grassroots

What is the nature of a movement that can challenge these dominant ideas? We argue that only a radical union movement that specifically sets out to widen class consciousness among student-workers can significantly improve living and working conditions for student-workers and provide a robust defense to the public education system. A business union model that does not emphasize grassroots organizing and rank and file participation can never achieve a meaningful change in consciousness, as one’s identity as a worker and a union member is only relevant the day that one signs a union card, votes in a union election, or happens to have an individual grievance with one’s employer. Furthermore, business union models have frequently sought to separate bread and butter union struggles from broader social justice struggles like the fight for public education. Finally, a business union model that seeks concessions to management does not acknowledge the absolutely deplorable nature of our working and living conditions. It is only when we recognize ourselves as having rights to exercise in the present that we are no longer willing to put up with these conditions. In this way, we argue that class-consciousness cannot be a nominal, unimportant category. The labor of organizing has to constantly draw attention to the implications of our situation as academic workers. As workers who are getting paid $17,000 a year, we have to understand our identity as one which is oppositional to the identity of highly-paid managers who have little to no connection with education provision. Academic Workers for a Democratic Union (AWDU) and affiliated rank and file movements have consistently worked to change these perceptions.

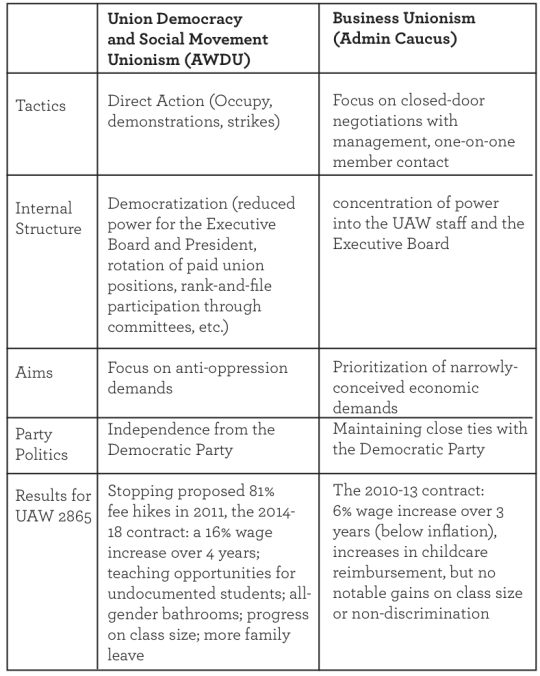

In 2010, activists founded AWDU to transform the union into “a social movement union that supports the empowerment of members through direct action.”[20] Named after Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU), AWDU’s first major campaign was a “No vote” campaign on the concessionary contract negotiated by the business unionist Admin Caucus in 2010, which lost but garnered 40% of the vote. Nevertheless, AWDU won control of the statewide union in the 2011 triennial election after a hotly contested campaign.[21] AWDU had to occupy the union offices for multiple days to demand that votes be counted, with support from dozens of labor scholars, after the Elections Committee, largely sympathetic to the Admin Caucus, stopped the vote count.[22] AWDU’s efforts to democratize our union opened up space to embrace a broader range of tactics and issues, which is essential for social movement unionism. As demonstrated in the table below, when union mobilizations result in meaningful gains for student-workers, it means that making claims for full citizenship now is worth the effort: we don’t have to settle for poor working and living conditions in the (indefinite) present. Doing so protects our own lives and dignity, helps to make inroads against the poverty and debt that affects so many of our members, and increases access to academic student-workers from working-class backgrounds.

Table 1: Social Movement Unionism and Business Unionism in UAW 2865

Class Consciousness and a Radical Academic

In the 1970s, hundreds of student leftists left campuses to take a job and organize in factories, as a so-called “industrializing” strategy; but today, campuses are themselves sites of labor struggles,[23] as AWDU’s experience illustrates. Graduate student-workers have been at the forefront of the resurgence of radical, grassroots unionism today, which is essential for revitalization of the labor movement.[24] For example, activists in the graduate union at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst also formed a radical caucus that won leadership of the entire amalgamated local in 2013, and have been building a grassroots, active, militant union; and it was the TAA, the graduate union at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, that sparked the month-long occupation of the Wisconsin State Capitol in 2011.[25] In contrast to the declining power of the labor movement generally, ASW unionization has been expanding; for example, ASWs at New York University won union recognition in 2013, with a landslide margin of 98.4% voting in favor.[26] The growing unionization movement among student-workers is evidence that student-workers are making claims to full social citizenship in the present.[27] Indeed, the oft-invoked separation between intellectuals and “workers” is increasingly obsolete, as academics, we are ourselves exploited, indebted and/or unemployed due to the corporatization of higher education. Therefore, protecting ourselves from exploitation as workers may also be one of the only ways to protect our lives as students, as it is harder to accomplish one’s own research when working as a TA for 75 students and working side jobs to make ends meet. In this way, fighting the proletarianization and exploitation that characterizes the public university is synonymous with protecting the university’s mission of research and intellectual life. Furthermore, organizing as exploited academic workers, upon whom higher education is increasingly coming to rely, enables us to struggle in solidarity with students for high-quality, accessible, public higher education. Not only are decent working conditions for teachers essential for provision of quality education, academic workers as workers have the (potential) capacity to disrupt operations of a university, which after all is the fundamental source of power for workers in a capitalist society.[28]

Where Karl Marx saw exploitation at the point of production as the key site of labor struggle, Karl Polanyi also theorized about struggles over commodification in the market. Through this lens, we can see the fight for public education as a Polanyian struggle against privatization, where the movement of academic workers is a Marxian struggle against exploitation. Interestingly, these struggles are happening at the same time, in the same place. Are they one and the same movement? On one level we must answer in the affirmative, as militant labor unionism of ASWs played a pivotal role in California’s student struggles against tuition hikes, police brutality and privatization of higher education in general. Furthermore, the fight to improve labor and working conditions draws immediate attention to the fact that academic labor is being proletarianized, thus shedding light on the degradation of teaching and education that is happening in public universities. Yet the ultimate goal of the fight for public education might erode the basis of academic student unions as instructors; if we had a generous welfare state with broad support for higher education, graduate students would be guaranteed a livable stipend, and not have to fund our education through employment for the university. Such a fundamentally radical vision is shared by the fight for public education and labor struggles. Radical scholarship of the last decades has often proclaimed the “farewell to the working-class”, and suggested new agents of transformation, such as the “multitude.”[29] However, these new agents of social change have failed to halt the strengthening forces of capitalism over the past three decades. In the wake of yet another capitalist crisis, we need new politics of the working-class. Academic student-workers’ movements suggest the potential for new, militant, class-conscious labor unionism that combines struggles against exploitation and commodification. Only this type of union movement will be able to show solidarity with radical students movements and become a major participant in the struggle for public education.

Acknowledgements:

All activist scholarship comes out of collective struggle, and as such we are deeply indebted to all of our comrades we have worked with over the past years, many of whose thoughts and analysis have greatly informed our own. Hasta la victoria siempre!

References and Footnotes

- The academic unions at UC campuses originally affiliated with the radical and militant union. District 65, which had led many efforts to organize academic workers; however, financial problems prompted District 65 to affiliate with the United Auto Workers (UAW), taking many academic unions into the UAW. ↩

- California Department of Education. 1960. A Master Plan for Higher Education in California. Sacramento. ↩

- University of California Office of the President (UCOP). 2011b. UC Mandatory Student Charge Levels. (http://budget.ucop.edu/fees/documents/history_fees.pdf) Accessed Jul 1, 2014. ↩

- Meister, Bob. 2009. “Where Does UC Tuition Go?” Reclamations 0. (http://reclamationsjournal.org/issue01_bob_meister_where_does_tuition_go.html) Accessed Jul 1, 2014. University of California Office of the President (UCOP). 2011a. Statistical Summary and Data on UC Students, Faculty and Staff: April 2011. (http://legacy-its.ucop.edu/uwnews/stat/headcount_fte/apr2011/er1totf.pdf) Accessed Jul 1, 2014. ↩

- Gordon, Larry. 2011. “A First: UC Fees Exceed State Funding.” Los Angeles Times, Aug 22. (http://articles.latimes.com/2011/aug/22/local/la-me-college-pay-20110822). Accessed Jul 1, 2014. ↩

- Armstrong, Amanda and Paul Nadal. 2009. “Building Times: How Lines of Care Occupied Wheeler Hall.” Reclamations 1. (http://reclamationsjournal.org/issue01_armstrong_nadal.html) Accessed Jul 1, 2014. Advance the Struggle. 2010. Crisis and Consciousness: Reflections and Lessons from March 4th. (http://advancethestruggle.wordpress.com/2010/04/12/crisis-and-consciousness-reflections-and-lessons-from-march-4th/) Accessed Jul 1, 2014. ↩

- Ellison, Erin. 2013. “A Collective Narrative of Trying to Make It on $17,000 a Year.” Towards Mediocrity, Oct 28. (http://towardsmediocrity.tumblr.com/post/65348774923/collective) Accessed Jul 21, 2014. ↩

- Weissmann, Jordan. 2014. “Ph.D. Programs Have a Dirty Secret: Student Debt.” The Atlantic, Jan 16. (http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/01/phd-programs-have-a-dirty-secret-student-debt/283126/) Accessed Jul 1, 2014. ↩

- Curtis, John W. and Saranna Thornton. 2013. The Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession, 2012-13. Washington DC: American Association of University Professors. (http://www.aaup.org/file/2012-13Economic-Status-Report.pdf) Accessed Jul 1, 2014. ↩

- Ibid. pp. 7. ↩

- Curtis, John W. 2014. The Employment Status of Instructional Staff Members in Higher Education, Fall 2011. Washington DC: American Association of University Professors. (http://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/files/AAUP-InstrStaff2011-April2014.pdf) Accessed Jul 1, 2014, pp. 2. ↩

- National Labor Relations Board. 2004. Brown University v. UAW. 1-RC-21368. July 13. ↩

- Draper, Hal. 1965. Berkeley: The New Student Revolt. New York: Grove Press. Pp. 161-162. ↩

- We use the label Administrative Caucus to refer to the United for Social Economic Justice (USEJ) caucus and Student Workers for Inclusive Transparent Change (SWITCH) caucus of Local UAW 2865 because they held close ties to the Administrative Caucus leadership of the UAW International in 2011 and 2014 respectively. The Administrative Caucus of the UAW International has held the presidency continuously since 1940. ↩

- Sullivan, Richard. 2003. “Pyrrhic Victory at UC Santa Barbara: The Struggle for Labor’s New Identity.” In Deborah M. Herman and Julie M. Schmid (Eds.), Cogs in the Classroom Factory: the Changing Identity of Academic Labor. Westport, CT: Praeger. 91-116. ↩

- Smith, Sara R. 2014. What Have Members Got to Lose? A Perspective on the Upcoming UAW Election. Academic Workers for a Democratic Union. April 6. (http://awdu.net/2014/04/06/what-have-members-got-to-lose-a-perspective-on-the-upcoming-uaw-election/) Accessed Jul 1, 2014. ↩

- Moody, Kim. 2007. US Labor in Trouble and Transition: the Failure of Reform from Above, the Promise of Revival from Below. London: Verso. Brenner, Aaron, Robert Brenner and Cal Winslow (Eds). 2010. Rebel Rank and File: Labor Militancy and Revolt from Below During the Long 1970s. London: Verso. ↩

- Bousquet, Marc. How The University Works: Higher Education and the Low-Wage Nation. With a preface by Cary Nelson. New York: New York University Press, 2008. Pp. 154. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Academic Workers for a Democratic Union (AWDU). 2011. A Platform to Change UC and Change Our Union. (http://berkeleyuaw.wordpress.com/a-platform-to-change-uc-and-change-our-union/) Accessed Jul 1, 2014. ↩

- Eidlin, Barry. 2011. “Reformers Win in California Grad Union Election.” Labor Notes, May 10. (http://labornotes.org/blogs/2011/05/reformers-win-california-grad-union-election) Accessed July 1, 2014. ↩

- Ashmore, Wendy, et al. 2011. A Call for the Immediate Resumption of Vote Counts at UAW 2865. (http://berkeleyuaw.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/a-call-for-the-immediate-resumption-of-vote-counts-at-uaw-2865-05-02-11-1100am.pdf) Accessed Jul 1, 2014. Graves, Lucia. 2011. “Vote Counting to Resume After UC Grad Students Occupy Union Offices.” Huffington Post, May 4. (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/05/04/vote-counting-resumes-uc-grad-students-union_n_857600.html) Accessed Jul 1, 2014. ↩

- Mohandesi, Salar. 2014. “Between the Ivory Tower and the Assembly Line.” Viewpoint Magazine. March 27, 2014. Retrieved from http://viewpointmag.com/2014/03/27/between-the-ivory-tower-and-the-assembly-line/, July 1, 2014. ↩

- Brenner, Mark. 2013. “Reformers Resurgent? A Survey of Recent Rank-and-File Uprisings.” New Labor Forum 22: 78-84. ↩

- Waltman, Anna. 2014. “Left Strategies for the Academic Workers’ Movement.” Left Forum, New York, NY. May 31.; Buhle, Mari Jo. 2011. “The Wisconsin Idea.” In Mari Jo Buhle and Paul Buhle (eds.), It Started in Wisconsin: Dispatches from the Front Lines of the New Labor Protest. London: Verso. 22-25. ↩

- Greenhouse, Steven. 2013. “N.Y.U. Graduate Assistants to Join Auto Workers’ Union.” New York Times, Dec 12. (http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/13/nyregion/nyu-graduate-assistants-to-join-auto-workers-union.html) Accessed Jul 1, 2014. ↩

- Bousquet, Marc. How The University Works: Higher Education and the Low-Wage Nation. With a preface by Cary Nelson. New York: New York University Press, 2008. Pp. 155. ↩

- UAW 2865. 2013. “Towards Mediocrity: Administrative Mismanagement and the Decline of UC Education.” (http://www.uaw2865.org/wp-content/uploads/Towards-Mediocrity.Sept-2013.pdf) Accessed Jul 1. 2014. ↩

- Gorz, Andre. 1982. Farewell to the Working-Class: an Essay on Post-Industrial Socialism. London: Pluto Press; Negri, Antonio and Michael Hardt. 2000. Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ↩