Inland Migration: Migratory Patterns to the Inland Empire from California Coastal Cities & Resulting Anti-Immigration Sentiment

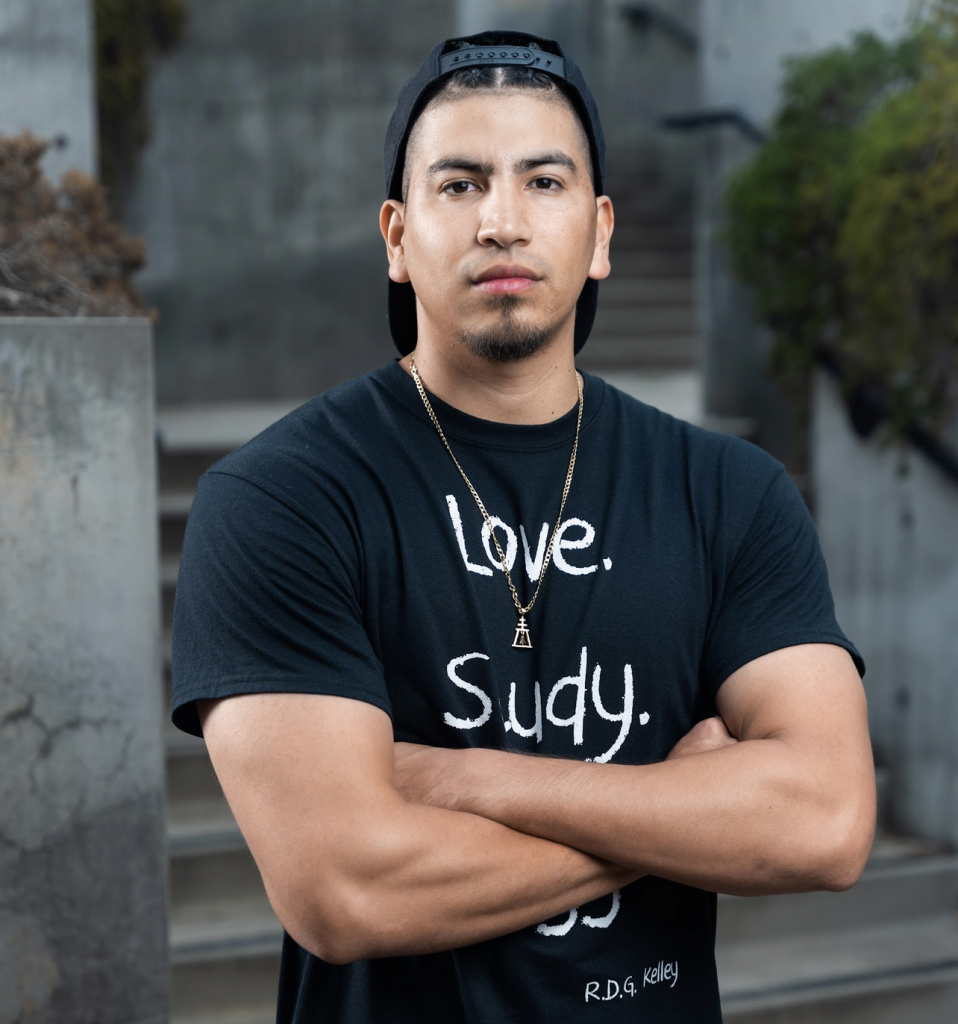

Humberto Flores

In 2014, a group of 200 to 300 people gathered to block three buses delivering unaccompanied children from Central America that was on its way to a local border patrol station. Protestors held American flags and signs that read “Stop illegal immigration” and repeatedly shouted, “Send them back!” Immigration officials eventually turned the buses around (De Lara 2016). In the next few days, tensions arose as pro-immigrant advocates in Riverside County challenged anti-immigration policies. At the time I lived in a predominantly Latinx city 20 miles north of Murrieta and I felt the presence of anti-immigrant policies. For instance, I recall seeing U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement trucks on street corners, targeting and terrorizing local street vendors. As anti-immigration and Latinx regimes began to appear, I questioned how we got here? The ensuing essay will explore the Inland Empire’s changes in recent decades, including population shifts, increased surveillance, policing, criminalization of the new majority-Latinx population, and local advocacy efforts.

The Inland Empire: A Majority-Minority Region

Riverside and San Bernardino Counties comprise Southern California’s Inland Empire. These counties include large immigrant populations; there are nearly 1 million immigrants living in the Inland Empire, with a ratio of one in five residents being an immigrant (UCR Social Innovation 2020). Immigration and migration are closely linked and often interchangeable but, in this paper, I distinguish immigration as the movement from one country to another; in contrast to migration, which is the general movement of people, within a country for instance (Bailey 2010). The primary driver of the Inland Empire’s population growth is migration from coastal cities, such as Los Angeles, Orange, and San Diego Counties. In particular, Los Angeles County is the primary origin of Inland Empire migrants. Regardless of origin, the Inland Empire’s population grew from 3.9 million in 2005 to about 4.9 million in 2015, due to (im)migration (Johnson, Reed, and Hayes 2008). With this change came a rapid demographic transformation from white to majority (56%) Latinx, transforming it into a majority-minority region (Gonzales 2013).

De Lara (2016) highlights that the new Inland Empire ethnic plurality posed new challenges to the mostly white existing political establishment. The Inland Empire has historically served as a refuge for white conservatives, which have been confronted with demographic changes. During the first wave of migration in the 19th century, white families moved to the area from Los Angeles and built up an agricultural citrus industry. The citrus farm required an agricultural workforce and landowners turned to Latinxs and Asians for labor. This resulted in white elites holding power over the minority working class. World War II triggered a second round of migration for work, resulting in thousands of Latinx, Black, and Asian working-class people moving into the Inland Empire. However, regional demographic changes were not even across the Inland Empire. The cities of Riverside, San Bernardino, Perris, and Ontario have high Latinx populations. San Bernardino and Moreno Valley gained the highest Black population. Other areas such as Rancho Cucamonga, Temecula, and Murrieta remained whiter, more affluent, and upscale areas.

A University of Southern California study further highlights the dramatic population growth of the Inland Empire (Terriquez et al. 2010). Approximately 22 percent of the population currently living in this region are immigrants. Further, approximately 75 percent of the region has arrived since 1980. Mexican-origin immigration doubled from 35 percent to 61 percent from 1980 to 2010. The Inland Empire has been California’s fastest-growing region since 2010, largely due to the housing booms and the exploding logistic-warehousing industry (Gonzales 2013). According to Census data, the Inland Empire added 47,601 people in 2021, being the fifth biggest gain among the 50 largest metro US cities (Lansner 2022).

The Birth of the “Warehouse Empire.”

Black and predominately Latinx folks migrate from the greater Los Angeles area to the Inland Empire in search of housing and employment opportunities (Gonzales 2013). In fact, my family who is of Mexican origin moved from Los Angeles to the Inland Empire in the 1990s in search of affordable housing. Additionally, my parents, brothers, and I have all worked in local warehouses. Consequently, the Inland Empire is now home to a growing number of Latinx and Black folks. The Inland Empire is now often referred to as the “Warehouse Empire.” There are at least 4,300 concrete box warehouses in the Inland Empire covering an estimated 1 billion square feet of the region and counting (Redford Conservancy 2021).

In many inland neighborhoods, you can spot warehouses overshadowing homes and apartments which not only leads to poverty but also poor air quality, both of which can have long-term effects. The American Lung Association gave Riverside an “F” grade, warning that “If you live in Riverside County, the air you breathe may put your health at risk” (American Lung Association 2022). The warehousing boom in Riverside has increased emissions from diesel trucks and trains. Breathing these emissions leads to respiratory problems, among other chronic health illnesses (Sasser et al. 2022). UC Riverside researchers also noted that warehouse workers, along with their families, are vulnerable to health effects associated with air pollution caused by the overflow of warehouses and diesel-fueled trucks. These previously mentioned conditions exacerbate COVID-19 risks due to pre-existing vulnerabilities. Particularly, air pollution was cited as an important factor for determining morbidity or mortality risk during the novel COVID-19 pandemic (Sasser et al. 2021).

Figure 1. Warehouses looming over Inland Empire homes. (Photograph courtesy of Brian van der Brug / LA Times)

Policing and Criminalization of Black and Brown Bodies and Undocumented Communities

With the shift of demographics during the last three decades, Riverside and San Bernardino Counties have increased the policing of Black and Brown bodies. Due to hyper-policing of the Inland Empire, the two counties are home to 15.8 percent of California’s incarcerated population, despite comprising only 11.8 percent of the state’s general population (Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice 2016). Further, the two counties also have a history of civil gang injunctions that criminalize non-gang-involved Latinx and Black residents by imposing curfews aggressively enforcing “no loitering” rules, individualized harassment of people, and effectively barring them from being merely present in public. Durán (2009) finds that the practice of gang enforcement stereotyping Black and Latinx communities as gang “infested” and equating gangs as synonymous with crime no longer emphasizes criminal acts, but rather criminalizes the people in the neighborhood. As a result of these policies, I was regularly stopped by the gang unit, searched, and questioned about gang membership in my own neighborhood. Additionally, most of the people I grew up with have served either local jail, state, or federal prison time.

Owing to the increasingly large Latinx population in the Inland Empire, politicians, and sheriff’s departments have implemented policies that target people of color, whether intentionally or not. For example, Kohout (2009) argues that geography is integral to the construction of immigration politics and policy. He described San Bernardino as a “struggling industrial city.” Latinx people make up 48% of San Bernardino; it is also an extremely poor city, both by the measure of the people and the city budget itself. San Bernardino also has high crime rates and in 2022, it was ranked the most dangerous city in the state of California (Asperin 2022). In 2006, a local “activist” formed the Save Our State (SOS) coalition, which claimed that San Bernardino’s troubles were caused by “illegal immigrants.” The SOS proposed an ordinance called “The City of San Bernardino Illegal Immigration Relief Act,” which would ban the city from using tax dollars to set up labor centers for undocumented immigrants and require the city to deny business permits to those employing undocumented immigrants, as well as impose large fines to landlords renting to unauthorized immigrants. This ordinance was copied nationwide, particularly in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, where it was eventually struck down by the court in response to efforts by the American Civil Liberties Union and other organizers (Kohout 2009).

Anti-immigrant advocates argued that undocumented immigrants were breaking the law, should have no rights to social services, and bring crime, diseases, and poverty to San Bernardino. Further, Kohout mentions that anti-immigrant advocates believed that undocumented immigrants turned San Bernardino into Compton or South Central. Supporters of the Illegal Immigration Relief Act also argued that language and assimilation are a point of contention. They pointed out that many undocumented immigrants demanded Spanish services and refused to learn English, and thus did not want to assimilate.

In the early 2000s, demographic changes in the Inland Empire shifted the political majority from white conservatives to Latinx liberals (Kohout 2009). Even though the region’s demographics shifted, and the white population declined, white voters maintained a disproportionate share of the voting base. Still, there was a large sense of white resentment, a response from white people who saw an increase in migrants as a threat to white property and power. To illustrate, the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR) formed alongside SOS, and both groups opposed immigration. Anti-immigration sentiments remained high in white jurisdictions, and they strived to change policies as demographics changed. While some cities opposed and protested against the Arizona SB 1070 law, otherwise known as the “show me your papers bill,” predominantly white cities in the Inland Empire expressed their support for it (De Lara 2016). SB 1070 invites racial profiling of Latinxs by allowing Police to demand papers and investigate immigration status if they suspect a person is undocumented (ACLU 2010). Discriminatory policies (i.e, SB 1070) supported by anti-immigrant organizations such as the SOS and FAIR are comparable to white resentment in the 1930s that resulted in restrictions and policies that were implemented in response to Black urbanization to “keep the cities white” (Wild 1991).

Further, the Riverside County Board of Supervisors responded to the growing immigrant population by mobilizing local law enforcement agencies to apprehend, detain, and deport all unauthorized immigrants (De Lara 2016). Riverside rationalized this tough law and order approach by portraying immigrants as “criminals.” San Bernardino further illustrated this point by pointing to policies such as 287(g), which maintained that the public is safer by getting rid of “dangerous criminals.” The 287(g) program became law as part of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, which allowed state and local law enforcement officers to collaborate with the federal government to enforce federal immigration laws (American Immigration Council 2012). Some local residents expressed they would gladly pay an increased tax to increase policing if it resulted in deportations and “safety.” In 2008 and 2009 the Riverside office of the U.S. Border Patrol carried out a series of raids across the region. Border patrol agents targeted day labor centers, bus stops, and predominantly Latinx neighborhoods. Although members of Inland Congregations United for Change successfully pressured the sheriffs in the Inland Empire to not renew the county’s 287(g) agreement with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; community members accused local law enforcement of still participating in cording the sweeps which advocates claimed violates policy 287(g).

De Lara (2016) notes that local police were turning anyone who was undocumented over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Riverside County Sheriff Stanly Sniff was a leading opponent of the TRUST bill, which limits the police’s ability to deport arrestees. This did not stop Inland Empire police departments from implementing their own policies that targeted immigrants. For example, the San Bernardino and Moreno Valley police departments have used sobriety checks to stop and impound the cars of thousands of unlicensed immigrant drivers (De Lara 2016). These checkpoints were justified as public safety measures that reduce drunk driving but in reality targeted Latinx neighborhoods.

The significant inland migration of Latinx people not only led to the criminalization of undocumented people as previously mentioned but also to the implementation of civil gang injunctions that target non-gang-involved Black and Latinx Riverside and San Bernardino residents (Maxson et al. 2004). The ACLU defines a gang injunction as a civil court order that attempts to address crime. Law enforcement uses gang injunctions as a tool to label people gang members and restrict their daily activities in a given area. Gang injunctions make it illegal to ride the bus with a friend or pick up a spouse from work late at night (ACLU 2010).

The San Bernardino Police Department filed gang injunctions against local Black and Latinx gangs such as Verdugo Flats, Seventh Street Gang, Sur Crazy Ones, Delman Heights, Five Times, etc. These injunctions were implemented during the late 1990s and early 2000s as Inland Empire demographics rapidly changed due to (im)migration. The San Bernardino Verdugo Flats gang injunction prohibited twenty-two activities, which included a night curfew, public association with defendants, and selling drugs. Gang injunctions in Riverside have similarly been implemented on gangs such as the Eastside Riva among many others around the county (FBI 2010). During this time there was also conflict between local homegrown neighborhoods and Los Angeles gangs that were migrating eastward.

The existing legal scholarship also documents how gang injunctions lead to the criminalization of the daily lives of many young people of color in low-income communities (Caldwell 2010). The use of injunctions labels and marginalizes people who the police consider to be gang members. Caldwell (2010) provides an example of a twelve-year-old Mexican-American boy who was riding his bike around the neighborhood and was labeled as a gang member by local police officers due to his brother’s affiliation. The boy was served with a gang injunction despite not being a gang member. The young boy then told his mother “If they’re going to treat me like a gang member, I might as well be one” and joined the gang at the age of fourteen, resulting in a self-fulfilling prophecy. This is an example of labeling theory and young Latinx kids being criminalized by the implementation of gang injunctions in racially minoritized communities.

Implications: Advocacy and Pushback

Immigrant rights advocates are relatively new in the Inland Empire and historically have not had much impact on policy-making decisions yet, (De Lara 2016) but recent organizations that have emerged are now beginning to challenge anti-immigrant bills. Organizations such as Inland Congregations United for Change have emerged to advocate for social justice policies and bettering the Inland Empire community overall, which challenge discriminatory policies. Additionally, the Inland Coalition for Immigrant Justice (ICIJ), which is composed of over 35 organizations advocates for the (estimated 300,000) (un)documented immigrants in the Inland Empire. The coalition focuses on policy advocacy, community organizing, and responding to ICE and border patrol operations. Most recently ICIJ has been advocating to shut down the Adelanto Detention Center, health care for everyone- regardless of immigration status, and supporting street vendors. Additional organizations such as the Community Action Teams (CAT-911), a community crisis response and a community alternative to 911, also aim to provide transformative justice training, organizing against police violence, and care for the Inland Empire. The Inland Empire is one case of anti-immigration policies, hyper-policing, and industrial-warehouse environmental racism. I encourage scholars, activists, and everyday people living in communities throughout the U.S. from other large metro regions that tend to get relatively little attention from national media with similar demographic trends such as Fresno, Anaheim, Phoenix, and El Paso, to look beyond the present case that may encourage a broader view toward understanding and organizing against anti-(im)migrant policies and movements.

Figure 2. A depiction of the immigrant Latinx community in Riverside. (Photograph by author Humberto Flores)

References

American Civil Liberties Union. 2010.“Gang Injunctions Fact Sheet.” ACLU of Northern CA. Retrieved January 12, 2022 (https://www.aclunc.org/article/gang-injunctions-fact-sheet).

American Civil Liberties Union. 2010. “SB 1070 at the Supreme Court: What’s at Stake.” American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved March 5, 2023 (https://www.aclu.org/sb-1070-supreme-court-whats-stake).

American Immigration Council. 2012. “The 287(g) Program: An Overview.” American Immigration Council. Retrieved January 12, 2022 (https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/287g-program-immigration).

Asperin, Alexa M. 2022. “These Are California’s Most Dangerous Cities.” FOX 11. Retrieved January 12, 2022 (https://www.foxla.com/news/california-most-dangerous-cities).

Bailey, Rayna. 2010. Immigration and Migration. New York, NY: Infobase Publishing.

Caldwell, Beth. 2009. “Criminalizing Day-to-Day Life: A Socio-Legal Critique of Gang Injunctions.” American Journal of Criminal Law 37(3):241–90.

Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice. 2016. “California Sentencing Institute.” Retrieved January 12, 2022 (http://casi.cjcj.org/).

De Lara, Juan. 2016. Unsettled Americans: Metropolitan Context and Civic Leadership for Immigrant Integration. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Durán, Robert J. 2009. “Legitimated Oppression: Inner-City Mexican American Experiences with Police Gang Enforcement.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 38(2):143–68.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2010. “Riverside Gang with Links to Mexican Mafia Targeted in Federal Case That Alleges Methamphetamine Trafficking.” FBI. Retrieved January 12, 2022 (https://www.fbi.gov/losangeles/press-releases/2010/la012710.htm).

Gonzales, Alfonso. 2013. Reform Without Justice: Latino Migrant Politics and the Homeland Security State. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Johnson, Hans P., Deborah Reed, and Joseph Michael Hayes. 2008. The Inland Empire in 2015. San Francisco, CA: Public Policy Institute of CA.

Kohout, Michal. 2009. “Immigration Politics in California’s Inland Empire.” Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers 71:120–43.

Lansner, Jonathan. 2022. “Inland Empire Population Growth 5th Largest in the US.” Press Enterprise, March 28, 2022. Retrieved November 15, 2022

(https://www.pressenterprise.com/2022/03/28/inland-empire-population-growth-5th-largest-in-the-us/).

Lung.org. 2022. “Riverside | American Lung Association.” Retrieved November 15, 2022 (https://www.lung.org/research/sota/city-rankings/states/california/riverside).

Maxson, Cheryl L., Karen Hennigan, David Sloane, and Kathy A. Kolnick. 2004. “Can Civil Gang Injunctions Change Communities? A Community Assessment of the Impact of Civil Gang Injunctions.” U.S. Department of Justice 99.

Robert Redford Conservancy for Southern California Sustainability. 2021. Pitzer College.“Mapping and Environmental Data Visualization.” Retrieved January 12, 2022

(https://www.pitzer.edu/redfordconservancy/mapping-data-visualization/).

Sasser, Jade S., Bronwyn Leebaw, Cesunica Ivey, Brandon Brown, Chikako Takeshita, and Alexander Nguyen. 2021. “Commentary: Intersectional Perspectives on COVID-19 Exposure.” Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 31(3):401–3.

Terriquez, Veronica, Ángel Mendiola Ross, Olivia Rodriguez, Jazmine Miles, and Rocio Aguayo. 2010 “Emerging Youth Power in the Inland Empire.” 26. Retrieved January 12, 2022 (https://transform.ucsc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/EmergingYouthPowerReport2021.pdf)

University of California, Riverside. 2020. “State of Immigrants in the Inland Empire.” Center for Social Innovation. Retrieved January 12, 2022 (https://socialinnovation.ucr.edu/state-immigrants-inland-empire).

Wild, Volker. 1991. “Black Competition or White Resentment? African Retailers in Salisbury 1935–1953.” Journal of Southern African Studies 17(2):177–90.

Humberto Flores is a PhD student in the Sociology Department at UC Santa Barbara studying police illegitimacy in Latinx communities. He holds a BA from UCLA and a MA from UC Riverside. Humberto is a Chicano first-generation college student born and raised in Riverside County. Coming of age in the Inland Empire, he witnessed the harsh policing practices endured by Black and Latinx residents. While his lived experiences with police and street violence, unfortunately, shaped much of his life, they also now fuel his intellectual curiosity.