Family Reconsidered

Mirna Nadia

The heterosexual nuclear family, as a social construct and normative ideal, is a composite of myths and aspirations for many and, in the case of Indonesia, for a nation. It has become the model of an ideal family, as seen in numerous government initiatives, most notably the national family planning program with its promise of happiness and prosperity. Indonesians who grew up in the 1970s–1990s are likely familiar with the program’s once ubiquitous slogan, keluarga kecil bahagia sejahtera, often translated as the small, happy, and prosperous family.

Predicated on the supposed advantage of a household economy with a gendered division of labor (men as breadwinners and women as unpaid caregivers), the heterosexual nuclear family privileges certain bodies, practices, and relations. It rests upon the binary opposition wherein family ideals are produced alongside the relegation of any other practices and relations as deviants, segregating the privileged and the excluded.

The state, through public policies, affects family choices and household formation. So does the market through its labor and industries (O’Brien 2023). They may normalize and sanction a particular form of family and household while discouraging others. Furthermore, because the family is the primary site of social reproductive labor, the state and market also indirectly impact how care work might be managed and organized.

The hegemony of heterosexual nuclear families is maintained through disciplinary temporal norms that impose certain “life script” concerns about growth, individual and national progress, and heterosexual reproduction. Such a “life script” assumes that there is a proper biographical timeline that follows a linear “straight time” (Boellstorff 2007) or “chrononormativity” (Freeman 2010). It orients bodies to ways of living that are in sync with the dominant narratives of belonging and becoming. Yet, there will always be those who do not fit into this model. These include people who live alone, choose to remain single, and form other types of household arrangements instead of a nuclear family and its privatized household. In these realms of the “improper” and the “unfitting,” I see how the experiences of the four subjects presented in this essay confound the dichotomies of progress and decline and success and failure instilled within the dominant narratives.

In contemporary Indonesia, the decoupling between household formation and marriage is underway, albeit slowly. A household is no longer synonymous with the heterosexual nuclear family. However, most of the households remain in the form of heterosexual families comprising married adults and their children. As of 2022, there were only an estimated total of 4.52 percent of female and 1.49 percent of male heads of households who were unmarried, with the majority of them being under 24 years old (Statista 2024). On average, women get married at the age of 22 and give birth by the age of 23. The figures are only slightly higher in Jakarta, where, on average, women marry at the age of 23 and give birth by 24 (Global Data Lab 2024b, 2024a). For Indonesians, getting married and leaving the parental home are important rites of passage. Adulthood is often recognized only after they marry or provide for themselves leaving their parental home, regardless of age.

Drawing from an impulse to document lives beyond the heterosexual nuclear family, this project centers on unmarried female-born adults residing in and around urban Jakarta. Most of the subjects presented in this essay, although not all, are queer individuals whom I have met through mutual friends and circles. They are either highly educated, well-embedded in queer networks in Jakarta, or both. All had been engaging in jobs that often forced them to grapple with the instability that arises from a lack of long-term and secure employment. The experiences of the four subjects in this essay do not represent all lives outside the heterosexual nuclear family. Rather, the presence or absence of possible subjects and experiences merely reflect those that are more accessible and closer to my own.

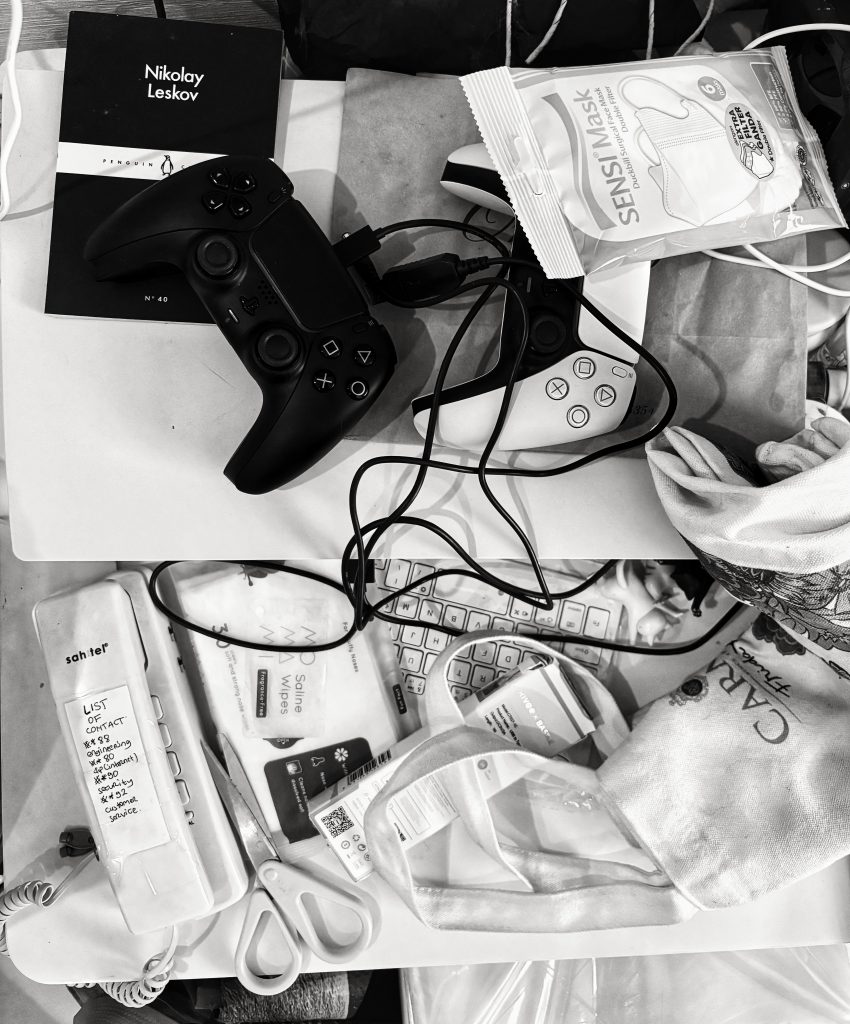

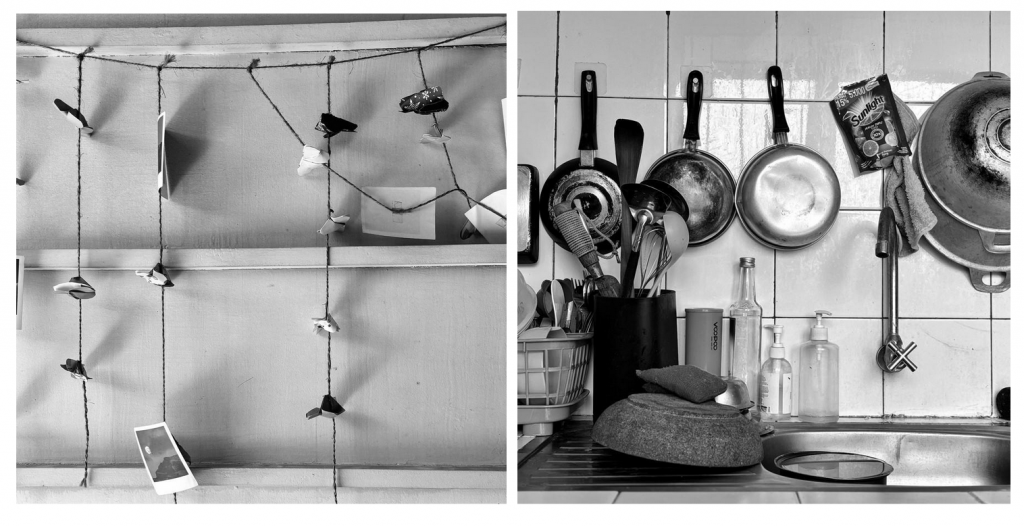

What started as conversations among a small group turned into a two-month project of collecting stories and attempting to document parts of their lives. Between October and November 2023, I visited individuals who agreed to participate in this project at their homes to take pictures and conduct short interviews. I relied on using a camera phone to avoid the intrusion of a more conspicuous photographic setup and reduce the subject’s stress of having to pose or perform in front of a camera. Photography as a medium reveals, evidently, what the narratives purport. If these photographs are evidence, however, they are inevitably partial. While they give the presumption of veracity that something does exist or once existed, they capture only fragments of mediated reality allowed to be brought into representation by the subjects and bound by my own interpretation and that of the viewers. All photographs featured in this essay are edited using a black-and-white filter to foster coherence in otherwise disparate lives. Such imposed coherence is intended to elude a sense of chronological temporality, suggesting that all exist and are captured in a singular present.

This project involved a process of crafting: there are decisions to be made and certain narratives that unfold from those choices. Some details are blurred, while others are sharpened. After all, it is not only the allure of the supposed truth that drives this project but also my fascination for stories—the every day and the imagined.

Moving Out and Apart

At the age of thirty-nine, Ririn lived alone in a spacious one-bedroom apartment in Central Jakarta. Her two cats were her only companions. Unmarried and with no child, Ririn admitted that she enjoys her current living arrangement, even though most women her age are already married and have a family their own.

Soon after graduating from university, she moved out of her family home and never returned. She confessed that living alone meant no one would chastise her for making a mess in the apartment or indulging in her hankering to buy numerous pairs of shoes. To her, adulthood came by way of self-sufficiency and being able to funnel money back to her family. Even so, it did not always free her from the familial and social expectations to form a family.

She realized that her unmarried status and reluctance to lean on her parental household meant she would have to depend on continuous participation in the labor market for her survival. At the time of this project, she was in-between jobs, having recently resigned from her post as a project leader for a non-profit organization based in Switzerland, and living on emergency funds while waiting for her next appointment with a better role at another organization.

She felt it was convenient to live alone, noting that many domestic duties, such as cleaning and cooking can be outsourced so long as one has the means. Working families often outsource domestic labor, as they rely on low-wage domestic workers and access to a wide range of service commodities such as meal delivery, laundry, and ride-hailing drivers. She, too, by relying on the service economy avoided the relentless housework that was typically split among household members, often the feminized ones.

Beyond managing care work, not having a family as a source of solace may cause people to feel powerless against the grind of life or fear abandonment at an old age. Still, she chooses not to be concerned about the future and makes the most of what life has to offer her at present, whether or not it involves marriage. “People often incorrectly assume that I avoided getting married. The truth is, I think it would be nice to have a family and have children,” Ririn admitted. The decision to delay starting a family did not necessarily imply a complete rejection of motherhood and family life, or a shift toward solitude. She said that the only thing she wished for was a way to change the “contract” so she could thrive while raising a family. There is nothing extraordinary about wanting and forming a family. Only, she knows that it will cost her more than she is willing to pay.

Networks of Care

Bella (26, left in the above image) and Day (31, right in the above image) shared a two-bedroom apartment in central Jakarta. Having attended the same university, they became closer through a mutual connection. Day just ended her employment with an international non-profit organization when she moved in with Bella, whose previous roommate had to return to her family home due to a salary cut. Transitioning into less stable employment and pursuing more freelancing opportunities, Day discovered that living with Bella was a beneficial arrangement because they could share the rent and other expenses. Beyond pooling resources, both admitted that having a friend to talk to at home offers a respite from the long hours of working at their jobs.

Both unmarried, they sought alternative forms of household life beyond the heterosexual nuclear family, aspiring to foster ways of relating to other human beings that did not exert dominance. They advocate for a vision of collective care, with Day referring to it as a “chain of care” and Bella as the “distribution of care.” Both thought that care work should not rest solely on one person or be confined to private households defined by marital and blood relations.

Initially, Bella and Day planned to remain in their shared living arrangement for a year, but their working circumstances changed within weeks. Bella, who was working for a UN agency, decided to hand in her resignation letter, while a contract termination came earlier than expected for Day. Faced with financial uncertainties, both chose to move back to their family homes. Moving back entails a trade-off, relinquishing some of the freedom they had enjoyed in having their own household, yet both acknowledge the privilege of having a family as a ‘safety net’ to fall back on. In a setting where they cannot rely on government assistance and strong networks outside of the family, there is no cushioning for the financial blow that comes from such sudden unemployment. One is free, to some extent, to form families or households of their own choice, under the condition of maintaining employment. That is a condition that, time and again, is undeniable.

Reflecting on the pervasiveness of childhood trauma among her peers, Bella saw the heterosexual nuclear family as a fraught institution, emphasizing the importance of building networks aligned with the concept of care collectivization. For her, this would entail unlearning established norms and consciously embracing a different way of life. “This heterosexual nuclear family model is isolating while, as humans, we could have richer experiences. It is not only limiting but also makes us vulnerable to violence. We should problematize this old, established institution, put the norms to the test, and maybe we should ask: What other forms of relationships are possible? What can we do differently? Even if we don’t know if we’ll ever make it, maybe it is worth striving for,” Bella said.

When asked about the possibility of living up to their ideals about care work, family, and household formation, Bella and Day expressed hesitation. Despite these uncertainties, Bella remained hopeful, referencing Bernardine Evaristo’s (2019) book Girl, Women, Other as a potential blueprint for the life she desired. “The characters in Evaristo’s works live within loose networks that span across generations.” In her view, that is an antithesis to the privatized, isolating nuclear family and households. “Personal conflicts or clashes of values are inevitable, but there is no imposing moral prescription when it comes to intimate space,” she said. While she thought that such a network may not be ideal, she argues that: “It certainly breaks the water and allows for a certain fluidity for people to organize their lives, especially when it comes to forming a family and organizing careworkers or domestic labor.” Bella appealed to the many possibilities of togetherness in the layered otherness of the characters in Evaristo’s story. A new way of living and surviving in the world outside the heterosexual nuclear family.

Recomposing a Family

Born in 1982, Jey left their family home early in their teenage years. Leaving what they described as a broken home, they moved around a lot before settling in Jakarta. “The ‘home’ was broken both in a literal and figurative sense,” Jey chuckled. Their family dissolution was soon followed by the demolition of the house. They recalled having to stay with distant relatives and friends who would kindly take them in and treat them well. “I would not call what I’ve experienced menumpang, but you may see that it was,” Jey said. In Bahasa Indonesia, there is a term called menumpang, which roughly translates into the act of staying under someone else’s care. This term often carries a hint of shame. Jey told the stories with fondness, however, saying that they never had to feel ashamed of living with families other than their own. It was these experiences that they wanted to emulate when they finally could offer a home for others looking for a safe shelter.

When Jey came to Jakarta and found supportive networks among friends, they seized the chance to build new ways of living and caring for each other that do not have to conform to the heterosexual nuclear family model with its privatized household. What they envisioned was a communal life where sharing was the rule—whoever had the means to contribute would do so in any way possible, from paying electricity bills to supplying tobacco for their rolled cigarettes. It was a different arrangement from living in a boarding house (indekos). While it is common to live with others who are unrelated by blood or marital ties in a boarding house or other types of rental properties, such practice does not necessarily mean a break away from their parental household or family.

Recently, Jey left a former commune and moved into a new place with a partner and two friends who had lost their jobs. Although they realized that pooling resources was necessary to maintain a stable household, Jey never asked the other members to participate in a certain way. In order to support the household, Jey had been working as a ride-hailing driver, and whatever they and the other household members could not afford to pay for was raised through their networks. Not being recognized by the dominant institutions, particularly the state, shrank their options and means to access resources or assistance that they may need in a difficult time. This makes it hard for families or household arrangements that do not follow the heterosexual nuclear family model to survive.

Jey’s decision to avoid imposing specific expectations on the other members of the household allowed everyone to contribute in their own unique ways, ensuring a fair distribution of resources and fostering a strong sense of community among them. Moreover, their openness to networks extending beyond the household itself may help them evade the oppressive logic of the private family. By actively seeking support from external networks, they were able to tap into a wider range of resources and opportunities. This not only strengthens their overall resilience but also puts forward other possibilities other than relying on the state, the market, or the private family for support.

Home At Last

This essay combines criss-crossing narratives of four lives, pigeonholed, to show disruptive practices against the common way of living in Indonesia. It shows people whose bodies, life stories, and experiences are not in sync with the dominant narratives and the biographical timeline of “straight time” or “chrononormativity.”

What propels these adults, along with everyone else, to compose other forms of family and household does not need to be a family dissolution or a catastrophic event. To not feel at ease in their family home could be a signal of the wider female discontents and the beginning of a desperately needed transformation. There is an emphasis on building care networks that elide marital relationships and the reproduction of patriarchal relations. These are networks that do not necessarily entail the practice of coupling (monogamous or otherwise).

The struggle to leave their family and parental household is often perceived as a temporary phase before transitioning into supposedly more stable household arrangements, such as heterosexual marriage. No matter how fleeting, they show practices that attempt to break away from the hegemonic nuclear family and privatized households. To delay, to stop, or to defer disrupts the supposed linear biographical timeline and the dominant narratives geared toward maximizing human productivity. All seek a new composition, a story of their own, so they do not have to reproduce the past.

References

Boellstorff, Tom. 2007. “When Marriage Falls: Queer Coincidences in Straight Time.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 13(2–3):227–48. doi: 10.1215/10642684-2006-032.

Evaristo, Bernardine. 2019. Girl, Women, Other: A Novel. London: Penguin.

Freeman, Elizabeth. 2010. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Global Data Lab. 2024a. “Mean Age at First Birth of Women Aged 20-50.” Retrieved February 8, 2024 (https://globaldatalab.org/areadata/table/age1chw20/IDN/?levels=1+4).

Global Data Lab. 2024b. “Mean Age at First Marriage of Women Aged 20-50.” Retrieved February 8, 2024 (https://globaldatalab.org/areadata/table/agemarw20/IDN/).

O’Brien, M. E. 2023. Family Abolition: Capitalism and the Communizing of Care. London: Pluto Press.

Statista. 2024. “Indonesia: Singles as Household Heads by Age Group and Gender 2022.” Statista. Retrieved February 8, 2024 (https://www.statista.com/statistics/1286827/indonesia-singles-as-household-heads-by-age-group-and-gender/).