Abolishing “Feminist Jails”: Why Caging People Will Never Be Feminist

Isabella Irtifa

A Case Study of the Proposed “Women’s Center for Justice” in NYC and Movement Efforts

When one jail closes, it does not mean that another newer, more modern or more “progressive” cage should exist. Reformers have been working towards a proposed “gender-expansive” jail in New York City’s Harlem called the “Women’s Center for Justice.” The proposal purports to have more humane conditions for those incarcerated, which includes family reunification, skill building, and community rooms. The proposal was created by the Columbia Justice Lab, UT-Austin’s Prison and Jail Innovation Lab, and the Women’s Community Justice Association, among others. This comes as Rikers fully closes in 2027, offset by the opening of four more jails – including a borough-based jail in Queens – at a total cost of $8.7 billion (Haag 2019). As a part of the borough-based jail proposal, the city plans to create a new facility for women and gender-expansive people in the larger men’s jail in Kew Gardens, Queens (NYC: A Roadmap to Closing Rikers n.d.). As an alternative for gender expansive people, the proposed “Women’s Center for Justice” would convert the former Lincoln Correctional Facility, a no longer functioning Harlem jail, into a women’s jail, with advocates claiming it to be “feminist” and based in trauma-informed care (Columbia Justice Lab 2022). Prison abolitionists are fighting back against this proposal, arguing that no jail is feminist. Anti-carceral feminists argue that the prison industrial complex harms women and trans people, low-income communities, and communities of color. Expanding and building new jails – like the proposed Women’s Center for Justice – means criminalizing and incarcerating more people, causing further harm and abuse in vulnerable communities. As abolitionists see it, feminism demands the right to live free from violence, and incarceration is an inherently violent institution that relies on racialized policing, caging, and deprivation of rights.

Anti-carceral advocates argue that the foundational principles behind these approaches ignores the systemic, anti-Black, and criminalizing reality of the punishment industrial complex. Ultimately, investment in more jails requires diverting funding that could have been invested in non-carceral resources such as education, wellness, and mental health programs that would actually benefit women and trans people. Locking people in cages, no matter how “humane,” cannot be seen as a means of justice or healing. Tracing genealogies of women’s jails in the United States, this essay will demonstrate the importance of ending punitive, carceral punishment, and present imaginings of more just communities of care.

Looking at this jail proposal compared to other proposals is especially necessary because it purports to be progressive and feminist. The proposal itself states that “there should be an accessible, humane center that is separate from men and reduces harm, rather than exacerbating it…Jails are almost always designed with men in mind” (Columbia Justice Lab 2022:3). However, as history shows us, no cage – even conceived of with gender-expansive people “in mind” – has actually been progressive because caging in itself is not trauma-informed. The proposal blatantly ignores failed and violent histories of fraudulent gender-expansive jail claims that have instead increased gender-based violence, including rape and sexual assault of prisoners. Looking at this proposal necessitates learning from histories of brutality against incarcerated people and calls on all of us to ensure that the focus should be on closing jails rather than opening more. If a jail is built, it will be filled. The only way to realize the goal of supporting people affected by violence is to invest in trauma-informed approaches – those that come from ensuring people can live in freedom and dignity, and have the resources they need in the community to succeed and thrive.

This essay utilizes historical methodologies, analyzes primary text of the Columbia Justice Lab’s Women’s Center jail proposal, and reviews strategies of dismantling jails/prisons as a feminist project. Critically looking at literature on harms jails cause to communities, this essay argues that jails themselves operate as a borderland for the maintenance of a white supremacist social order and deprives people of their freedoms. As a second-generation immigrant and family member of people affected by the prison industrial complex and racialized policing, I look to expose how systems of criminalization and incarceration reproduce inequities and harm in our communities. This essay will also interrogate the oxymoron a “women’s jail” presents by deeming itself trauma-informed, when incarceration reinforces intergenerational psychological, physical, and spiritual harm. Referring to past “Women’s Jails” efforts, this essay draws on lessons learned through New York City’s most prominent symbol of women’s caging – Rosie’s and the House of Detention for Women. This essay will also explore harms of caging as punishment, carceral feminism versus abolition agendas, and ultimately why caging people will not ever be feminist.

A Brief History of “Women’s Jails”

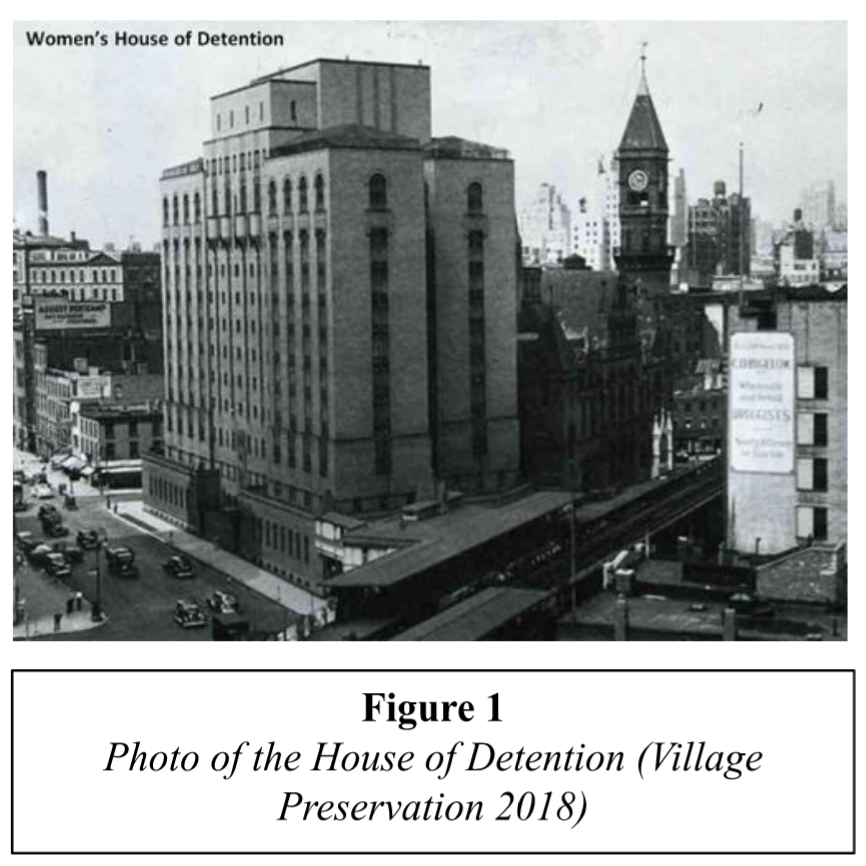

The New York Women’s House of Detention in Greenwich Village is one of the most well-known examples of women’s caging. Existing from 1932-1974, the House of Detention for Women was created with the intention of being responsive to incarcerated women’s needs and was supported by so-called progressive women’s activists and suffragists. In reality, the center reproduced violent structures of racism, misogyny, and class violence (Cunniff 2022). Given this history, those supporting and conceiving of the center did not interrogate how carceral punishment in general lead to torture and further harm to those incarcerated. As Cunniff (2022) writes, the argument ‘was not to “free them all’; instead, the progressive demand was to build ‘better’ cages. The House of Detention incarcerated largely Black and working-class people who were arrested on artificial charges, including that of protesting the Vietnam War, activism, drug possession, sex work, and other acts deemed “crimes.” The House of Detention was right next to city streets, so prisoners could communicate about the terrible conditions of the inside to people on the street who would listen (with pedestrians sometimes even advocating for them) (Cunniff 2022). Prisoners in the House of Detention included well known activists such as Andrea Dworkin, and abolitionists Angela Davis and Afeni Shakur. Ultimately, while conceived to be a more “humane” facility, the conditions of the prison were abysmal.

The Women’s House of Detention became infamous for its abuses. This is because it was not just used to house women detained before trial, as intended, but was also a vessel to incarcerate those who had been sentenced from Blackwell Island, which was a facility plagued by smallpox (Cunniff 2022). Other major concerns include accounts of overcrowding, disease, health neglect, sexual assault of prisoners by doctors and guards, forced medication, and frequent rebellions due to inhumane conditions (Cunniff 2022). Andrea Dworkin, jailed in the Women’s House of Detention as a freshman in college for protesting the Vietnam War, is featured in the book Hellhole, which details the horrible treatment Dworkin faced and the conditions of life in the prison (Harris 1967). Dworkin spent “4 days and nights in the filth and terror of that jail” (Stevens 1975). Dworkin describes being sent to be examined for venereal disease, but was then forced to have a doctor examine her breasts and stomach, and a prison doctor inserting his hands into both her rectum and vagina, “brutally applying” force (Harris 1967:16). In addition, Dworkin describes the unsanitary facilities with mice running throughout the cells. Dworkin’s testimony about this experience is what helped lead to the closure of the House of Detention. Angela Davis also describes accounts of people incarcerated being drugged with their meals. She writes:

Later I learned that these women received Thorazine with their meals each day and, even if they were completely sane, the tranquilizers would always make them uncommunicative and detached from their surroundings. After a few hours of watching them gaze silently into space, I felt as though I had been thrown into a nightmare (Gruen and Marceau 2022:305).

The Correctional Institution for Women (CIFW) in Rikers later opened in 1971 to address the abuses presented by the Women’s House of Detention. However, CIFW also became a major concern due to overcrowding, lack of medical care provisions, and assault (Shanahan 2022). Further proposals were developed to create a new, “better and improved” women’s jail with larger capacity, all of which actualized to similar horrific conditions.

In 1988, less than 20 years after CIFW opened, the Rose M. Singer Center (“Rosie’s”) opened in the Bronx. Rosie’s had a capacity of over 1,000 people and included a nursery for pregnant incarcerated soon-to-be mothers (Shanahan 2022; Cunniff 2022). Programs at the facility included or covered job training, gardening, sewing, and cooking. According to Singer, the woman after whom the center was named, it was meant to “be a place of hope and renewal” (Correction News 1988). Rosie’s was anything but a place of hope and renewal, and became known as a site of torture.

Rosie’s is a site of patriarchal violence, medical neglect, and mass death. Rosie’s is a “gender responsive” and “trauma informed” jail, but incarcerated people in the jail experience sexual violence, physical torment, and death. Some accounts have detailed invasive gynecologists who convinced patients they had cancer and unnecessarily cut into their cervix; people being denied the medication they have relied on for years; negligent medical response leading to death; and lack of support for drug withdrawal (Eichelberger 2015; McMillan 2015).

Campaigns to create new women’s jails have made promises of better conditions. For example, the Women’s Community Justice Association created a campaign called #BeyondRosies. In an effort to gain support of pro-carceral progressives, the campaign drew on the failings of Rosie’s to argue that the Women’s Center for Justice would be different (Cunniff 2022). The campaign lauded the Women’s Center for Justice in Harlem as a new vision for gender-expansive jail initiatives. However, as we see with previous attempted women’s jail and gender-expansive jail initiatives, these have all amounted to be torturous, inhumane, and not trauma-informed.

The treatment of people in prisons and in these gender-expansive jails are rooted in a racist, classist social order underpinning U.S. society. Samah Sisay, a lawyer and organizer, argues that imprisonment relies on histories of “sexual violence used to ‘discipline’ people on plantations and reservations, to the lynching of Black people criminalized for deviating from white supremacy’s gender and sexual politic edicts, to the historic and ongoing sterilization of people trapped in detention centers and prisons” (Sisay 2022). The proposal for the Harlem gender-expansive jail is more of the horrific status quo regarding the histories of gender-based violence. No matter how new jails are framed, history demonstrates that these abuses have not and will not be solved by the implementation of newer cages, and why we must embrace an abolitionist perspective.

Carceral Feminism v. Abolition

Carceral feminism fails to acknowledge how the prison industrial complex and criminal punishment bureaucracy hurt BIPOC and LGBTQI people. It ignores the increased intersection of policing, racialized surveillance, and state violence that leaves certain groups more vulnerable to abuse (Britton 2020). Carceral feminism in particular advocates for lengthening prison sentences that deal with feminist and gender issues, such as rape, and the belief that harsher sentences will help to solve these issues (Bernstein 2012). As seen with Rosie’s and the Center for Detention, longer sentencing and expansive jail processes do not benefit those it seeks to serve, and instead cause further harm and trauma.

Abolition feminism, on the other hand, seeks a world beyond policing and prisons. It also focuses on building realities outside of the systems we currently have, as these systems are built on racialized capitalism and policing that target Black, Indigenous, people of color, queer and gender-expansive people. Such targeted policing is evidenced by the fact that imprisonment rates are much higher for women of color than white women. In 2021, the imprisonment rate for Black women (62 per 100,000) was 1.6 times the rate of imprisonment for white women (38 per 100,000) (Monazzam and Budd 2023). We can see the same disparity in poverty rates, with the Census reporting Black individuals making up 13.5% of the population but 20.1% of the population in poverty in 2022 overall (United States Census Bureau 2023). Hispanics are also overrepresented in poverty with a ratio of 1.5 (United States Census Bureau 2023). Many of the communities living in poverty have also faced heightened policing, sentencing, and prosecution. The Sentencing Project in 2023 reported that more than two-thirds of people who are currently serving life sentences are people of color. Similarly, 55% of people serving life sentences without the possibility of parole are Black (Monazzam and Budd 2023).

Such racialized criminalization extends into education through the presence of police in schools. A 2014 investigation on discipline in schools led to the Department of Education and Justice to acknowledge that there are substantial racial disparities in discipline in schools that are not due to more frequent misbehavior by students of color, but likely due to racial bias (U.S. Department of Justice & Office for Civil Rights 2014). Another study found that if an individual is suspended between grades 7-12, the odds of incarceration in young adulthood increase by 288%, with Black individuals having significantly increased odds of incarceration compared to white people (Hemez, Brent, Mowen 2019). Such school-to-prison and abuse-to-prison pipelines result in cruel and intergenerational consequences for people living in poverty (Edelman 2019). Such consequences are detailed in a later section of this paper. Abolitionists argue that it is interconnected apparatuses like the school-to-prison pipeline and policing of low-income communities that lead to higher imprisonment for communities of color. If more jails and prisons are built – even ones that say they are gender-expansive and trauma-informed – they will be filled. Such logic then justifies the state’s increase in funding for policing that ultimately targets communities of color.

As Ruth Wilson Gilmore argues, abolition asks us to “look at the political category of crime and… [the need] to take it apart” (Intercepted 2020). The construction of “crime” itself must be examined for how it specifically punishes people who deviate from the white supremacist, settler, patriarchal norm (Hernández 2017). Beth Richie (2012) furthers this analysis by focusing on the ways Black women are especially targeted by the criminal legal system as a result of patriarchal violence and racialized oppression. To truly work towards a more just and liberatory future, goals of abolition must be intersectional. Abolitionists seek to embody transformative justice as practice and solve society’s issues that would render carceral solutions unnecessary. Abolition requires a deeper look at the structural conditions that lead people to act in harmful ways to one another, and necessitates an elimination of those inequalities to ultimately end the potential of perpetrating such harm (Kaba 2021). Abolitionists believe that systems of punishment are deeply racist and misogynistic, and need to be dismantled to end the root causes of violence (Kaba and Ritchie 2022).

Abolition also acknowledges the difference between “reformist reforms” versus abolitionist steps (Critical Resistance 2022). Reformist thinkers, such as those who support women’s jails, choose to “reform” the conditions in which people are still caged. Critical Resistance, an abolitionist organization, developed action guides to help discern whether a project is a “reformist reform” or an abolitionist, decarceral step toward ending imprisonment. In it, they ask: does the project reduce the number of people imprisoned or under another form of state control; reduce the reach of jails/prisons in our everyday lives; create resources and infrastructure that do not rely on police/prison guards; strengthen capacities to address harm that are rooted in community accountability (Critical Resistance 2022). In identifying a reformist reform, Critical Resistance argues that any new prison built will be filled, ultimately leading to the expansion of incarceration and more caging, even if the project was meant to improve conditions of those incarcerated. Resources that would be going towards “reformist reforms” must instead be utilized for projects that aim to build up community, end poverty and homelessness, and imagine futures outside of systems of degradation that impoverish communities.

Abolition focuses on building, creating, and imagining alternatives to incarceration. As Angela Davis (2003) writes after her abuse from incarceration:

[R]ather than try to imagine one single alternative to the existing system of incarceration, we might envision an array of alternatives that will require radical transformations of many aspects of our society. Alternatives that fail to address racism, male dominance, homophobia, class bias, and other structures of domination will not, in the final analysis, lead to decarceration and will not advance the goal of abolition.

To actualize abolition, transformative justice is an alternate approach to addressing harm. At its foundation, transformative justice works to counter violence while minimizing harm and ultimately actualizing justice for all parties (Mingus 2019; Dixon 2020; maree brown 2015). Transformative justice often does not rely on the state (police, prisons, criminal legal system), as the state is a violent, anti-Black, capitalist, and racialized institution that puts forth proposals that negatively target BIPOC and queer communities. State responses, as we have seen, often include tactics such as gender-expansive jails/prisons, even though they reinforce and perpetuate violence, both behind and outside of bars. Additionally, these strategies require sustained commitment and long-term organizing, rather than simply jailing someone. This means that solutions to harm are rooted in transformative justice – where the person who perpetrated the harm is supported to ensure that the harm does not happen again. This is a tactic of healing, dignity and care.

It is important to provide space for critiques of abolition. Those who believe that reforms are best suited to foster accountability and “justice” to individuals wronged argue that an end to carceral institutions does not center survivors of harm, or much less victim’s families who must heal after the harm has been done. Such is the mentality: ‘If they are locked away, my family will have justice and my community will be safer.’ This view argues that justice would be achieved from locking the perpetrator up and throwing away the key. However, it is important to look at the root causes of violence, the inequalities in our communities that may lead to “violent” behavior. Consider someone who is trying to provide for their family, or themselves, desperate to put food on the table, and how the reality of not making enough money to live can cause someone to resort to violent actions like robbery. Consider perhaps another poignant example of someone who commits harm due to a mental health episode, but they never had the monetary means to receive health support, medication, or care. Abolition, rather than reforms, prioritizes solutions that would eliminate causes of inequality and self-perpetuating violence.

Ultimately, locking people in a cage causes further harm, such as increased stress, lashing out which can lead to harm inflicted towards another person, and a complete loss of autonomy. Families and communities of those incarcerated are also harmed, which can lead to further violence. None of the conditions people experience in cages are consistent with the long-term healing of the individual and community, given the destructive consequences of imprisonment on mental health. Abolition argues that resources that go into sustaining prisons and their expansion should instead go towards funding community services like schools, mental health initiatives, after-school groups, and other programs that are conducive to the process of healing and are necessary to eliminate inequality that leads to violence. To further understand the importance of abolition, and how prisons are not conducive to healing or “rehabilitation,” it is necessary to delve deeper into the harms of incarceration as a racialized, gendered, and classed project.

Harms of Incarceration

Mass incarceration is a product of white supremacist institutionalized mechanisms of policing, surveillance, bond, and other targeted initiatives. Sandra Smith, a peer programming manager working with currently incarcerated people talks about her own experience in prison: “There is a specific trauma related to being incarcerated that is pretty much indescribable… First of all, it’s losing your liberties—losing the ability to do anything on your own. And you’re constantly being yelled at. You’re constantly being demeaned” (Huff 2022). It is critical to recognize that the realities of incarceration, regardless of how “humane” the facility purports to be, have lasting psychological and intergenerational effects that perpetuate cycles of trauma and abuse. Incarceration has major negative impacts on one’s ability to find stable employment, secure safe housing after release, and sustain connections with loved ones. Imprisonment has societal consequences: communities affected by incarceration are seen as being more “violent,” fueling greater disparities in state funding when, in actuality, the community is highly policed and therefore people are forcibly ensnared in the prison system. Incarceration also disproportionately targets people who are Black, Indigenous, queer, gender non-conforming, trans, or disabled. In 2021, The Sentencing Project published a report stating that Black people in the U.S. are imprisoned at five times the rate of white people. Similar disparities can be seen with people with disabilities, where compared to being 15% of the U.S. population, 40% of people in prison have a disability (Prison Policy Initiative, n.d.).

By its very nature, incarceration has the capacity to break someone’s spirit due to its imposed hierarchy. This can also lead to incarcerated people rebelling or becoming aggressive to themselves or one another. Angela Davis (1974) writes, “Jails and prisons are designed to break human beings, to convert the population into specimens in a zoo obedient to our keepers, but dangerous to each other.” Davis’ (1974) argument examines the relationship of people incarcerated to their peers, the penal system, and themselves. Being put in a cage leads to feelings of worthlessness, where people are in a “zoo” manipulated and abused by their “keepers.” Incarceration is hierarchical and therefore abusive in nature with the ultimate goal not of healing or respect, but of breaking spirits. Ruth Wilson Gilmore describes such a system as “incapacitation,” where people can be stopped from taking action inside prison walls that would allow them to feel autonomous (Intercepted 2020).

Imprisonment separates people from their community and loved ones, forcing them to feel isolated. In 2015, Goomany and Dickinson (2015) conducted research on the impact of incarceration on mental health, and isolation was identified as a major stressor leading to severe psychological distress. They found that even when receiving visits from family members while incarcerated, the environment of incarceration makes it harder to connect and feel like a whole person (Goomany and Dickinson 2015). Separation from families, loved ones, communities, and the outside world while incarcerated isolates people, disrupting social structures that are vital to live a fulfilling life. In discussing the consequences of border politics on people’s lived realities, Harsha Walia writes (2022), “Borders destroy communal social organization by operating through the logic of dispossession, capture, containment, and immobility.” Such a description of borders amplifies the entanglement Angela Davis and Gina Dent (2001) identify – that “the prison itself is a border.” Such regulations, isolation, and containment have a major impact on the relationship incarcerated people have with their families.

Parental separation from children is especially violent and isolating. An article in Behavioral Sciences & the Law argues, “Separation from children is one of the most stressful conditions of incarceration for women and is associated with feelings of guilt, anxiety, and fear of losing mother-child attachment” (Lindquist and Lindquist 1998). Another study conducted by Poehlmann (2005:353) found that “most mothers described an intense focus on feelings of distress, depression, or guilt.” One of her participants was a mother, who said, “All I’d do was cry. It is horrible being away from your kids, especially when they the only people who care for you” (Poehlmann 2005:353). In the same study, another participant said, “I was very hurt, depressed, crying constantly, and worried” (Poehlmann 2005:354). Poehlmann’s (2005:353) study found that approximately six percent of the mothers featured said that they were suicidal early in incarceration. Regardless of how “humane” a jail or carceral apparatus claims to be, the very structure of jails can have severe mental health and physical impacts. In addition, poor conditions and lack of appropriate medical care and responsiveness can cause additional suffering (World Health Organization 2020). The mental, physical, and psychological horrors discussed describe the reality of imprisonment, including in institutions that have previously claimed to be “feminist,” “gender-expansive,” and “trauma informed.”

No jail or proposed agenda can provide, especially in a punitive carceral context, the resources needed to serve communities and people deeply impacted by separation from loved ones and beloved activities. Prisons and jails are ultimately unfree places that deprive people of their freedom of movement and ability to live with dignity. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) reports that a “third of women in state prison, a sixth in federal prison, and a quarter in jail had been raped before their sentence” (Bureau of Justice Statistics 1999). The criminalization of vulnerable groups as targets for incarceration is highly gendered, sexed, ableist, and racist. It is especially important to note that policing and surveillance targets Black and brown people, and the proposed Women’s Jail in Harlem would further increase harm on communities of color, poor communities, and gender marginalized groups. As Price, the co-executive director of Grassroots Leadership argues, “It doesn’t matter what name you give it… [cages are] a dehumanizing place to put people” (Tamar 2022). Due to the harms of caging to human life, no one should be incarcerated, especially in any place that falsely purports that a new system of caging (i.e. gender-expansive jails/prisons) will be any different.

The New Harlem “Feminist Jail”

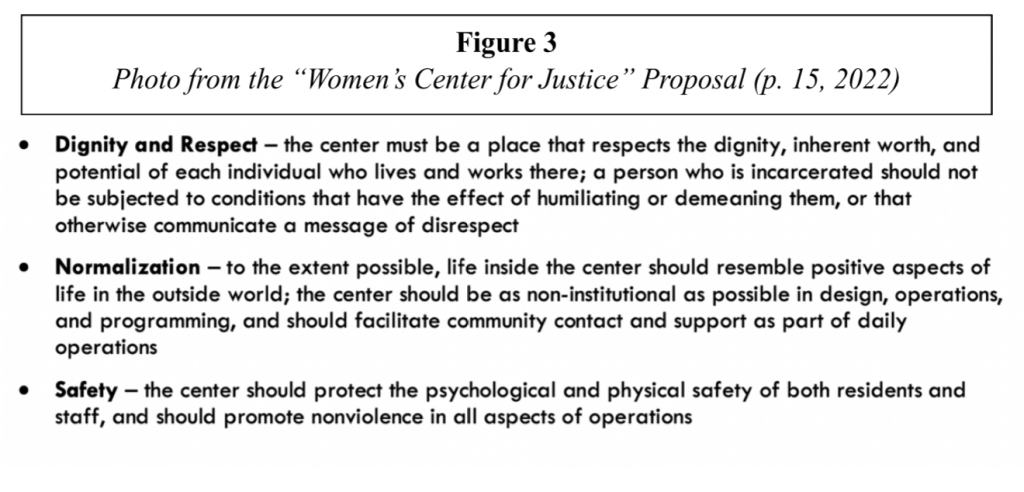

The Columbia Justice Lab, sponsor of the Women’s Center for Justice, published a proposal that outlines the goals of the Center, its implementation, and how it differs from gender-expansive centers of the past. The proposal was made in response to the call to close the Rose M. Singer Center (Rosie’s) on Rikers and place women and gender-expansive people in Kew Gardens, a facility that would be a part of the men’s jail. The proposal argues that gender-expansive groups would be safer at the Women’s Center for Justice, which is made “with them in mind” (Columbia Justice Lab 2022:3). However, a cage ever being designed with human needs and dignity “in mind” is a fallacy. If a jail is built, it will be filled, which leads to higher rates of incarceration specifically for gender-expansive people. The proposal is framed as a reform that offers a safer space for gender-expansive groups, and discusses how the center will be led by “effective strategies to create a safe, calming, and rehabilitative center” (Columbia Justice Lab 2022:15).

Many of the foundations of the center read as an oxymoron. Under “dignity and respect,” it states that no person should be subject to the effect of “humiliating or demeaning” treatment. However, punishment in its conception, the notion that no one can have freedom of movement, is demeaning. This would also entail that the center would need to hire “feminist guards” that are all specifically trained in gender care. As we learn from Rosie’s, the medical neglect and torture that took place highlights how these centers do not provide proper care in practice if the system one is caged in is based on punitive measures. The very nature of having a jail entails prisoners and guards, leading to hierarchies, power differentials, and cycles of violence (Foucault 1995). Additionally, the proposal reads that safety is the highest priority with an emphasis on promoting nonviolence in the facility. However, it is imperative to remember that prisons and jails, and any carceral substitute, are violent institutions that rely on taking individual freedoms away as punishment. If the center were to be a truly safe and dignified space, it would prioritize a transformative justice approach and not rely on carcerality.

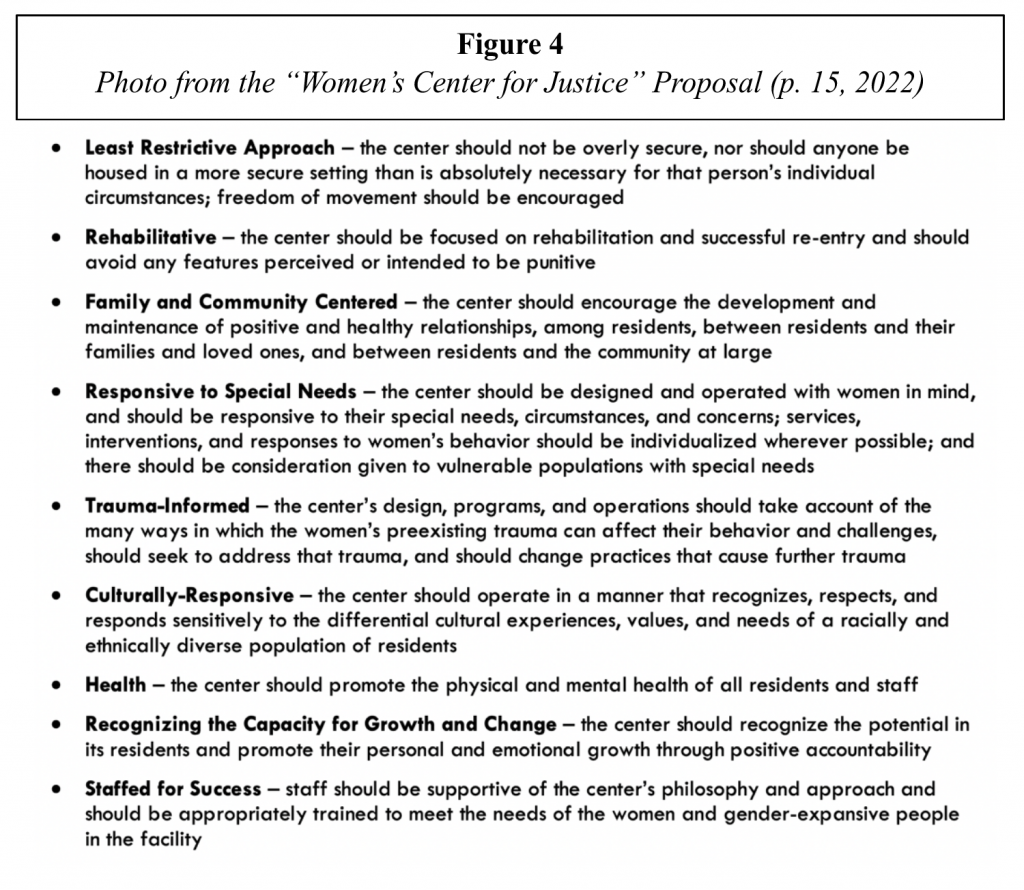

The proposed Women’s Center for Justice is not fundamentally different from existing women’s jails despite the proposal’s insistence on its innovation. Previous proposals with similar plans purported to have common areas, windows, and access to the outside world, but continued to have widespread abuses and create trauma for prisoners. The Center for Justice goes as far as to say that they aim to adopt the “least restrictive approach” where people are not “housed in a more secure setting than is absolutely necessary” (Columbia Justice Lab 2022:15). Here, it is evident that the center is glorifying their plans and not recognizing that incarceration itself is restrictive. Again, those incarcerated are unable to leave which is fundamentally in opposition to a “least restrictive approach” (Columbia Justice Lab 2022:15). It is natural for people when their freedoms are taken away to feel scared and defensive, and protect their own safety as they may be re-exposed to trauma. Using restrictive approaches when people incarcerated are not obedient to those in charge is a weapon against the people incarcerated and is ultimately punitive. Similarly, the claim that the center is “trauma informed” ignores the reality that the very institution of a jail can cause further trauma and suffering to those incarcerated.

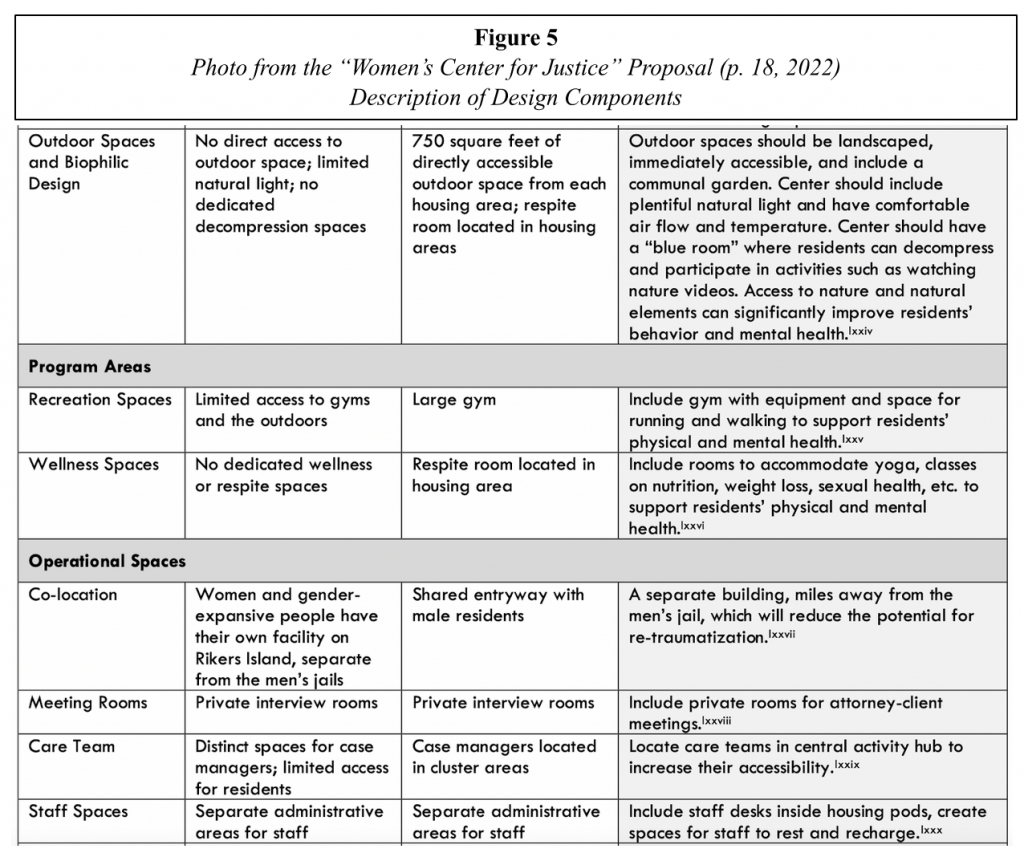

The proposal further details the differences between the Singer center, the current Kew Gardens plan provided by the city, and the new proposal for the Women’s Center for Justice. These plans include details on housing areas, staffing, programming, operational spaces, and more. Those that support the Women’s Center say the facility will look and feel more domestic with less surveillance from guards. Columbia Justice Lab argues that this will be especially important in promoting the dignity and well-being of those incarcerated. What is particularly concerning about this is the overt glorification of the incarceration facility. The stakes of the proposal are dire: if the Center were to be built, it would ignore histories of abuses against gender-expansive groups and the brutality underpinning the very conception of jails/prisons. What the Center’s proposal presents is not a desire to have people live with freedom, but instead is a demand for better caging systems. Such rhetoric perpetuates the prison industrial complex’s far-reaching harms to the most vulnerable communities.

In the below comparative chart, Columbia Justice Lab (2022:18) describes the Women’s Center for Justice as a space where incarcerated people can do “yoga,” be a part of the “community garden” and visit outdoor spaces that are “landscaped” where they can “decompress… [and engage] in activities such as watching nature videos.” The proposal overlooks the inherent violence that exists in a facility that does not allow people to leave, to hug their children, to visit their families, to travel, and to heal. The facility is a cage. In including this language, they reinforce the assumption that a jail is the only avenue to rehabilitation, which is untrue. Other means include investing in communities through mental health programs, food justice, and mutual aid, as well as ensuring people have access to healthcare and the basic resources they need to live sustainable and peaceful lives. Additionally, Rosie’s, also meant to be a gender-expansive jail with the primary goal of reducing recidivism, became a torture chamber for many gender-marginalized people.

As Mon Moha, a New York-based community organizer asks,

“A lot of the framework for the women’s jail is that it’s staffed by social workers instead of correctional officers, that it would offer more access to therapy… I think the basic question is why does someone need to be incarcerated in order to receive that kind of care?” (Tamar 2022).

Columbia’s Abuses in Harlem

The jail proposal is the latest iteration of the deep and ongoing history of anti-Black violence and displacement in the surrounding Harlem neighborhood perpetuated by Columbia University and its affiliates (Black Students’ Organization at Columbia University 2018-2019). Columbia has continuously published plans to develop into Harlem, which entail increasing their policing and security task-forces in the Harlem area. In recalling my own graduate experience at Columbia University, as a part of our orientation, all students were asked to attend a presentation in which a plan for Columbia’s development was articulated. The plan lauded initiatives to extend security buildings and innovative think tank consortium campuses up into Harlem/Manhattanville. Students were both disgusted and in awe, clearly aware of the implications this would have on the surrounding community.

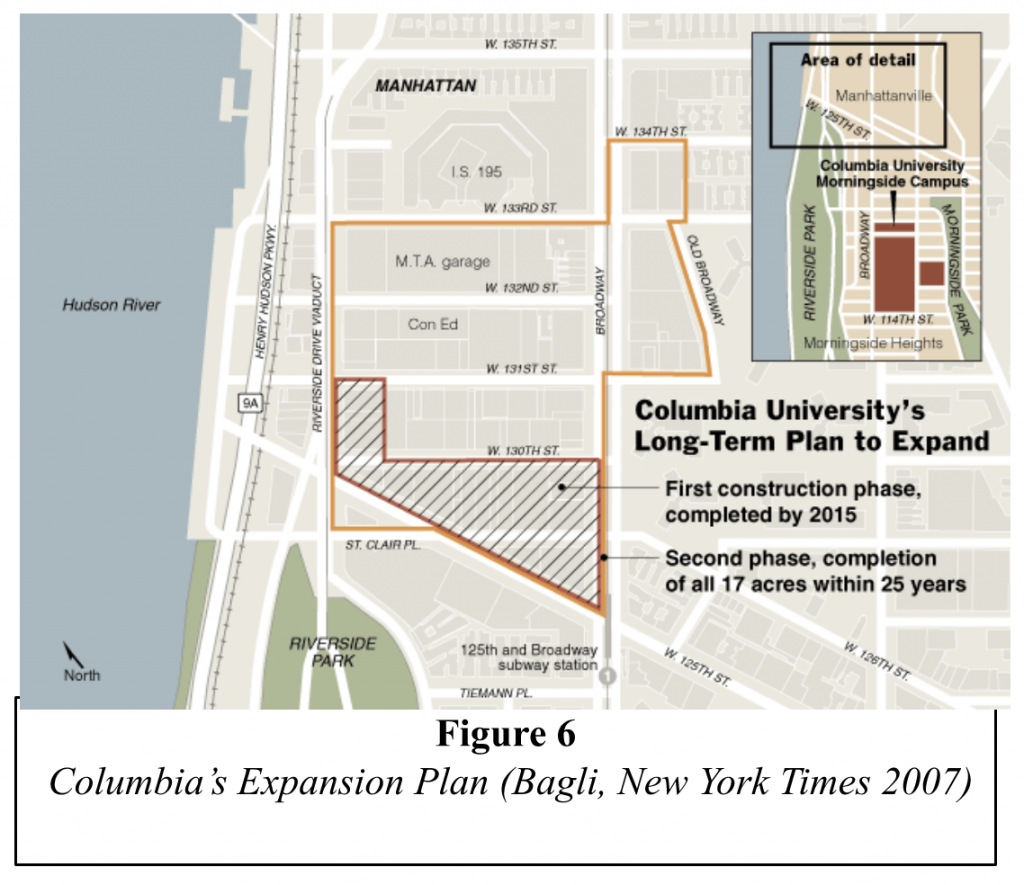

Columbia University’s development plan is shown in the map below, and displays how the campus is gentrifying up into historically Black Harlem and subsequently pushing out Black and brown residents. Morningside Heights, Harlem, and nearby Columbia University are becoming increasingly more affluent over time. The Neighborhood Projects People of NYC Seminar (n.d.) at Macaulay, CUNY published that the median family income rose from $33,000 in 1980 to $56,500 in 1997. Additionally, the proportion of families earning over $150,000 a year more than doubled between 1990 and 1997. Similarly, since 1968, Columbia purchased and converted more than 6000 units of affordable, rent-regulated housing for its own use and expansion, and has since made no guarantee it will preserve a significant amount of affordable housing units (Coalition Against Gentrification, n.d.). The neighborhood directly north of Columbia is largely Black, Hispanic and Latine (United States Census Bureau, n.d.) However, the inhabitants of the area are becoming increasingly younger, likely due to students moving into the area, leading to higher rents which force historic communities to become rent-burdened or displaced (United States Census Bureau, n.d.). Community organizers and students at Columbia argue that the jail plan in Harlem – a predominantly Black neighborhood with a history of radical activism and resistance – is a direct attack on criminalized Black, poor, migrant, queer, gender-expansive, and disabled communities, justified under the guise of progress and academic innovation. Columbia’s resources, agendas, proposal developments, and collaborations are actively deploying carceral initiatives in historically Black neighborhoods. Communities write in an open letter calling for an end to the Harlem jail proposal: “The plan treats historically Black, Latinx, and working-class neighborhoods as the ideal settings for jails. Most of those who would be sent to this “Women’s Center for Justice” are Black and Latinx survivors of gendered violence and systemic racism” (“An Open Letter,” 2022). Columbia University has contributed to the mass criminalization of Harlem residents through its deployment of University “Public Safety,” NYPD presence, and surveillance mechanisms, and this plan only forwards their support of racialized geographies of incarceration. The jail’s presence could mean increased police presence, surveillance, and police contact with residents who may thereby become targeted by this regime and ultimately entrapped in the growing prison industrial complex.

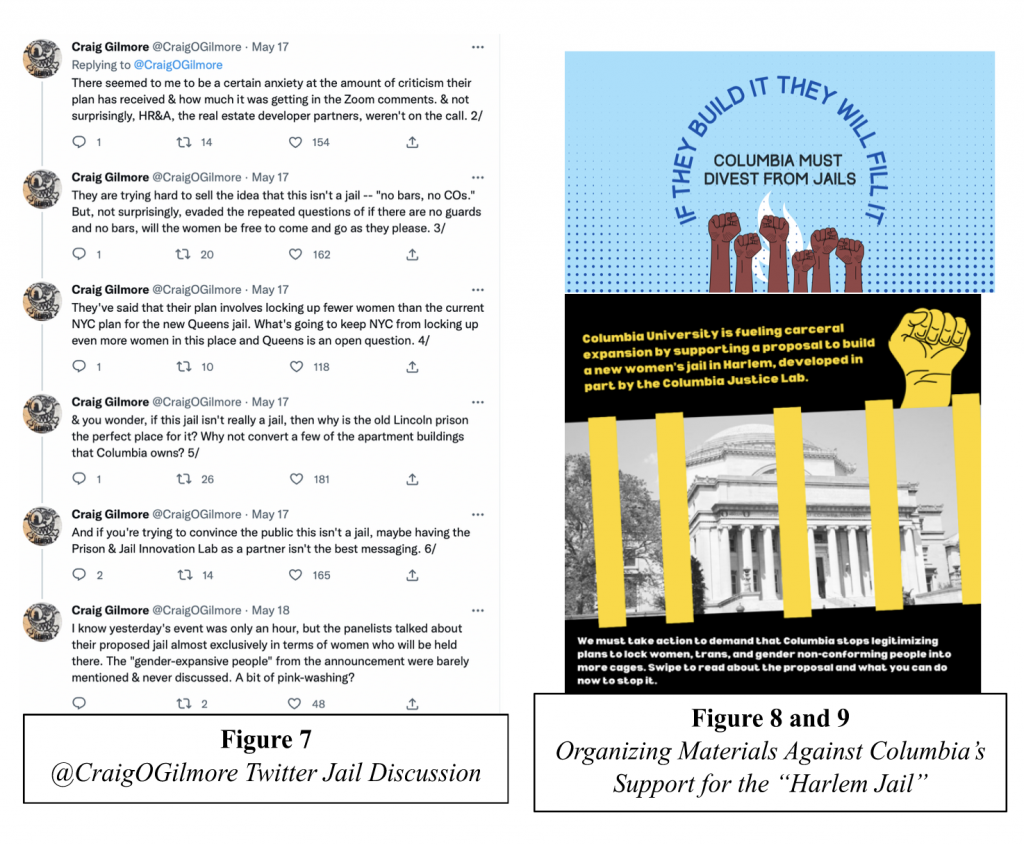

The Columbia Justice Lab held a briefing for the public on its plans for the Center. Craig Gilmore (@CraigOGilmore) discussed what he witnessed on Twitter. The Women’s Center for Justice is often framed as not a jail, but a trauma-informed rehabilitative space. However, a place in which people are monitored, surveilled, controlled in every aspect from time outside to food they eat, and cannot leave, remains exactly the same as the ideas it was predicated on – the Women’s Center for Justice is a cage that creates unfreedom. The Women’s Center for Justice would be built in the area of the Lincoln Correctional Facility, which is located near the northeastern corner of Central Park. The area is predominantly Black and Hispanic with over 30% of the population in the area living in poverty (United States Census Bureau 2022 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates). With a jail in the area, the police would have more resources and propensity to target local community members who may already be marginalized and vulnerable. This may put those that live near the jail in more danger and harm from policing in the area.

As Craig Gilmore notes, if the center is not a jail, why is the old Lincoln prison a perfect place for it? Why make carceral institutions into newly developed “feminist” centers if it is not also a part of a carceral institution? Columbia students and the public agreed and created a media campaign that went viral on Twitter and in many news outlets. The campaign tied together other campaigns to #FreeThemAll, #NoMoreJails, and end Columbia’s abuses in Harlem, as well as identifying Columbia Justice Lab members that were a part of the proposal. As they argue, no jail could ever be feminist, especially one that continues to push out and incarcerate Black and brown people.

Why Abolition is Necessary

Creating more jails that are “humane” is impossible because at its base carceral systems are punitive and rely on taking away people’s freedoms. Proposing a “gender-expansive” and “feminist” jail is not a safety measure, and it instead perpetuates violence. Revoking people’s freedom of mobility, ripping families and communities apart, arresting people, and traumatic police encounters are all a part of the violence that is the prison industrial complex and jail expansion. These practices are the foundational elements of incarceration, and the proposed jail will still operate as a jail, holding people in a cage without escape. The only humane solution is freeing all people, not investing in creating new cages.

To have a truly restorative platform through abolition we need to build up our communities and our support systems. This means re-allocating the billions of dollars used for creating news jails to instead go to housing, safe shelters, public education, healthcare, mental health services, community wellness programs, transportation. We need to invest in care, not carcerality. Care cannot occur in a cage. People need to be with their community, receive services of support, and be able to engage in initiatives that work to heal harm. There is no such thing as a feminist jail. Jails, prisons, and other carceral-like substitutes are violence.

We must invest in decriminalization, reparations, and community-based care to address the structural roots of violence. The only solution that is feminist, gender-affirming, anti-racist, anti-colonial, and trauma-informed is one that allows people their freedom of movement, freedom to make decisions, freedom for people to be themselves, and freedom for people to seek care and support in their communities and be met with love and compassion.

References

adrienne maree brown. 2015. What is/isn’t transformative justice? Retrieved February 1 2024 (Adriennemareebrown.net).

“An Open Letter Demanding Community Services and An End to Pretrial Detention and Gender-Based Imprisonment in New York.” 2022. Medium. Retrieved March 1 2024 (https://medium.com/@nonewwomensjailnyc/over-200-community-members-organizers-scholars-and-formerly-incarcerated-people-and-their-ce9218e021ba).

Bagli, Charles V. 2007. “Planning Panel Approves Columbia Expansion.” New York Times. Retrieved February 1 2024 (https://archive.nytimes.com/cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/11/26/planning-panel-approves-columbia-expansion/).

Bernstein, E. 2012. “Carceral politics as gender justice? The “traffic in women” and neoliberal circuits of crime, sex, and rights.” Theory and Society 41(3):233–259.

Britton, Hannah E. 2020. Ending Gender-Based Violence: Justice and Community in South Africa. University of Illinois Press.

Bureau of Justice Statistics Selected Findings. 1999. “Prior Abuse Reported by Inmates and Probationers.” Written by Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D. BJS Statistician. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Retrieved March 1 2024 (https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/parip.pdf).

Coalition Against Gentrification. n.d. “Columbia’s West Harlem Expansion.” Retrieved February 2 2024 (https://coalitionagainstgentrification.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/scegbookletshort-edge.pdf).

Columbia Justice Lab. 2022. “The Women’s Center for Justice A Nation-Leading Approach on Women & Gender-Expansive People in Jail.” Retrieved February 5 2024 (https://justicelab.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/Womens%20Center%20for%20Justice.pdf).

Columbia University Black Students’ Organization. 2018-2019. “A Brief History of Anti-Black Violence and Policing at Columbia University.” Retrieved February 5 2024 (https://drive.google.com/file/d/163tgQpWNfFpnQez5D6zzX7cpU-UqApNY/view).

@CraigOGilmore. “I listened to an hour of Columbia Justice Lab, Women’s Community Justice Association & the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab pitch their new feminist jail.” X, 17 May 2022, https://twitter.com/CraigOGilmore/status/1526675014300336131.

Critical Resistance. 2022. “Reformist Reforms vs. Abolitionist Steps in Policing.” Retrieved January 20 2024 (https://criticalresistance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/CR_abolitioniststeps_antiexpansion_2021_eng.pdf).

Cunniff, Abby. 2022. “NYC Activists Push Back Against Proposed “Feminist” Women’s Jail in Harlem.” Truthout. Retrieved February 4 2024 (https://truthout.org/articles/nyc-activists-push-back-against-proposed-feminist-womens-jail-in-harlem/).

Davis, A. 1974. Angela Davis: An Autobiography. International Publishers Co.

Davis, A. 2003. Are Prisons Obsolete? Seven Stories Press.

Davis, Angela and Gina Dent. 2001. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 26(4):1235-1241.

Dixon, Ejeris and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha. 2020. Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement. AK Press.

Edelman, Peter. 2019. Not a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in America. The New Press.

Eichelberger, E. 2015. “You Call This A Medical Emergency?” Death and Neglect at Rikers Island Women’s Jail. The Intercept. Retrieved November 15 2023 (https://theintercept.com/2015/05/29/death-rikers-womens-jail/).

Foucault, Michel. 1995. Discipline and Punish. New York: Vintage Books.

Goomany, A. & Dickinson, T. 2015. “The influence of prison climate on the mental health of adult prisoners: a literature review.” Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 22(6), 413-422.

Gruen, Lori and Justin Marceau. 2022. Carceral Logics: Human Incarceration and Animal Captivity. Cambridge University Press.

Haag, Matthew. 2019. “4 Jails in 5 Boroughs: The $8.7 Billion Puzzle Over How to Close Rikers.” New York Times.

Harris, S. 1967. Hellhole: The Shocking Story of the Inmates and Life in the New York City Women’s House of Detention. Dutton.

Hemez, Paul and John J. Brent and Thomas J. Mowen. 2019. “Exploring the School-to-Prison Pipeline: How School Suspensions Influence Incarceration During Young Adulthood.” Youth Violence Juv Justice 18(3):235-255.

Hernández, Kelly Lyttle. 2017. City of Inmates. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

Huff, Charlotte. 2022. “The Formerly Incarcerated are Helping Newly Released Prisoners Cope with Life After Prison.” American Psychological Association 53(7).

Intercepted. 2020. “Ruth Wilson Gilmore Makes the Case for Abolition.” The Intercept. Retrieved November 12 2023 (https://theintercept.com/2020/06/10/ruth-wilson-gilmore-makes-the-case-for-abolition/).

Kaba, Mariame. 2021. We Do This Till We Free Us. Haymarket Books.

Kaba, Mariame and Andrea Ritchie. 2022. No More Police: A Case for Abolition. The New Press.

Lindiquist, Christine H. & Lindiquist, Charles A. 1998. “Gender differences in distress: mental health consequences of environmental stress among jail inmates.” 15(4):503-523.

McMillan, Cecily. 2015. “The Rikers Nightmare is Far From Over.” Al Jazeera. Retrieved November 15 2023 (http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2015/7/the-rikers-nightmare-is-far-from-over.html).

Mingus, Mia. 2019. “Transformative Justice: A Brief Description.” Leaving Evidence.

Monazzam, Niki and Kristen M. Budd. 2023. “Incarcerated Women and Girls.” The Sentencing Project. Retrieved February 1 2024 (https://www.sentencingproject.org/fact-sheet/incarcerated-women-and-girls/).

Neighborhood Projects, The People of NYC Seminar. n.d. “Gentrification Process.” Macaulay Honors College. Retrieved February 2 2024 (https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/beemanneighborhoods/gentrificationprocess/).

NYC: A Roadmap to Closing Rikers. n.d. “Closing Rikers: Queens Garage and Community Space.” Retrieved April 5 2024 (https://rikers.cityofnewyork.us/queens-detention-facility/).

Poehlmann, J. 2005. “Incarcerated Mothers’ Contact With Children, Perceived Family Relationships, and Depressive Symptoms.” Journal of Family Psychology 19(3):350-7.

Prison Policy Initiative. n.d. “Disability.” Retrieved January 25 2024 (https://www.prisonpolicy.org/research/disability/#:~:text=People%20with%20disabilities%20are%20overrepresented,state%20prisons%20have%20a%20disability).

Ransom, J. & Bromwich, J. 2022. “Tracking the Deaths in New York City’s Jail System in 2022.” New York Times. Retrieved November 15 2023 (https://www.nytimes.com/article/rikers-deaths-jail.html).

Richie, Beth E. 2012. Arrested Justice: Black Women, Violence, and America’s Prison Nation. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Shanahan, J. 2022. Captives: How Rikers Island Took New York City Hostage. Verso Books.

Sisay, Samah Mcgona. 2022. “Opinion: Rejecting the Notion of a ‘Feminist’ Jail for Harlem.” City Limits. Retrieved March 1 2024 (https://citylimits.org/2022/07/14/opinion-rejecting-the-notion-of-a-feminist-jail-for-harlem/).

Stevens, W. 1975. Off our backs: Index, the first five years, 1970-1974. Washington, D.C.: Off our backs.

Sarai, Tamar. 2022. “Abolitionists Push Back Against New York City’s Proposed Plan For a ‘Feminist Jail.’” Next City. Retrieved November 15 2023 (https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/abolitionists-push-back-against-new-york-citys-proposed-plan-for-a-feminist).

United States Census Bureau. 2023. “Black Individuals Had Record Low Official Poverty Rate in 2022.” Retrieved January 2 2024 (https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/09/black-poverty-rate.html#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20Black%20individuals%20made,poverty%20(ratio%20of%201.5).

United States Census Bureau. n.d. “Census Tract 186; New York County; New York.” Retrieved February 2 2024 (https://data.census.gov/profile/Census_Tract_186;_New_York_County;_New_York?g=1400000US36061018600#income-and-poverty).

United States Census Bureau. n.d. “Census Tract 219; New York County; New York.” Retrieved February 2 2024 (https://data.census.gov/profile/Census_Tract_219;_New_York_County;_New_York?g=1400000US36061021900).

United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division and United States Department of Education Office of Civil Rights. 2014. “Dear Colleague Letter on the Nondiscriminatory Administration of School Discipline.” Retrieved January 1 2024 (https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201401-title-vi.pdf).

Walia, Harsha. 2022. “The Border Wall is Not A Wall.” Boston Review. Retrieved November 16 2023 (https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/matthew-longo-shadow-wall/).

World Health Organization. 2020. “UNODC, WHO, UNAIDS and OHCHR joint statement on COVID-19 in prisons and other closed settings.” Retrieved November 17 2023 (https://www.who.int/news/item/13-05-2020-unodc-who-unaids-and-ohchr-joint-statement-on-covid-19-in-prisons-and-other-closed-settings).

Isabella Irtifa is a bi-racial second-generation immigrant, community organizer, and PhD student at the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities. Her research focuses on the intersection of border abolition and critical race theory. She is committed to building communities of care through organizing against the impacts of settler colonialism and state violence. Isabella graduated with her masters from the Institute for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University, and holds a bachelors degree in Sociology and Ethnic Studies. Her work can be found in The Sociological Review Magazine, UN Women reports, and Watzek, among others.