Prologue: Black in White Space

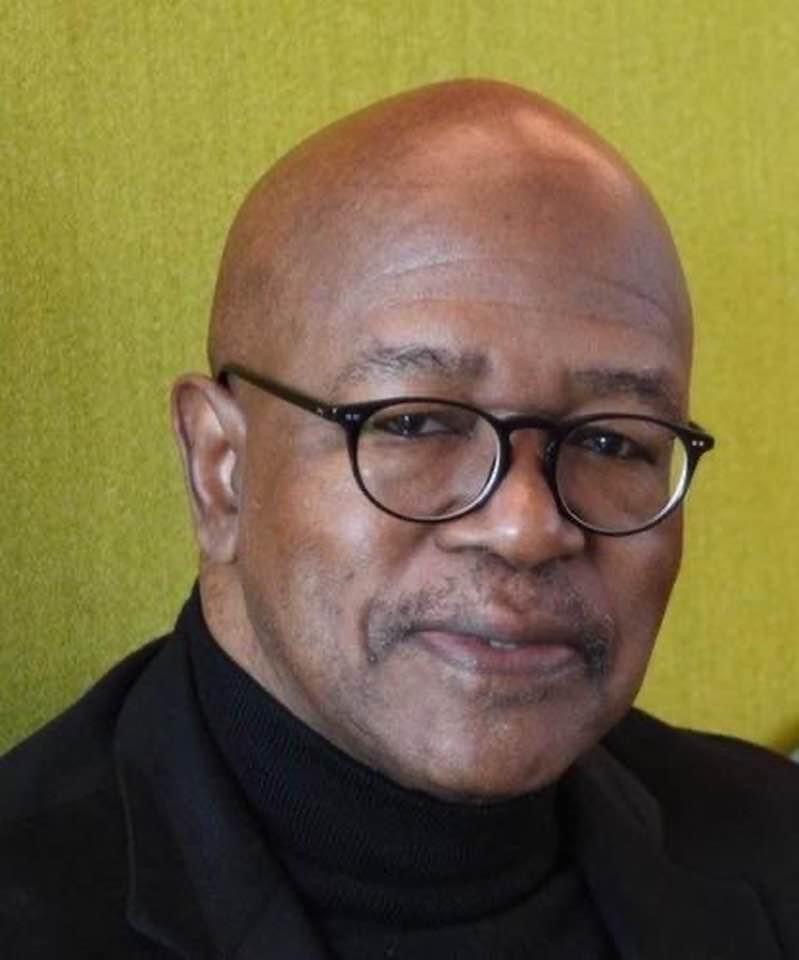

Elijah Anderson

Excerpt reprinted with permission from Black in White Space: The Enduring Impact of Color in Everyday Life by Elijah Anderson. Published by the University of Chicago Press. Copyright 2021. All rights reserved.

I was born in the South on what used to be a plantation. My grandmother, a sort of village doctor who never accepted payment for her services, was the midwife at my birth. She was a religious woman who lived by the Bible, so she named me Elijah. My mother, who had an eleventh-grade education, was twenty years old when I was born and already had three children.

Her family members were sharecroppers, so she went to the field each day to pick cotton, as did my grandmother and my father.1 In those days, when crops needed to be planted or harvested, school would let out because that work took priority. My father attended school only to the fourth grade, but in World War II he drove a supply truck in the US Army in England and then in France. After returning from the war, he felt he could no longer live as a second-class citizen in the South. He believed he would encounter trouble there, and a better life in the North beckoned.

The factory jobs of the North were a magnet for rural southerners, both Black and White. My uncles had already migrated to South Bend, Indiana, and my family followed them there. Once in South Bend, my mother worked as a domestic, working “days” in the homes of well-to-do Whites, and my father, like my uncles, found a job at the (now-defunct) Studebaker automobile factory. For many years he worked in the foundry there. And at age seventy- one, after breathing soot and metallic dust over decades, my father died of lung cancer, though he’d never smoked.

While my parents struggled to establish themselves in South Bend, for the first two years my sister and I boarded next door to my uncle in the home of a woman I called Aunt Freddie, who had migrated to the North in 1910. An educated, proper middle-class Black woman, she read me Bible stories and had a great influence on me.

Eventually my family moved into an apartment in a segregated part of the city. When I started public school at age five, I was one of only a handful of Black students at the excellent Oliver School, the result of a racially gerrymandered school district. By contrast, later, when we moved into our own home in an “integrated” neighborhood that was in effect transitioning from White to Black, I entered a segregated Black school. By the time I graduated from high school, the neighborhood was totally Black.

In the second grade, I learned to read at an advanced level, and the teacher would sometimes stand me in front of the class to read aloud. Not surprisingly, because I was the teacher’s pet, my friendships were limited and I felt on the margins.

As an independent child who loved the freedom of being out late at night, I began to run with other boys who gravitated to the streets. I had jobs after school, starting with selling the South Bend Tribune on downtown street corners at age ten. On occasion I supplemented my spending money by organizing other boys to take the bus with me to White neighborhoods to rake leaves, shovel snow, or even sing Christmas carols for money.

At age twelve I secured the adult job of setting pins at a downtown bowling alley. Most of my coworkers were winos and homeless men, along with other young boys like me, and I loved being part of the life of these “grown people.” Around them we young boys could smoke and curse and act grown- up ourselves with few sanctions. Because setting pins and handling bowling balls caused too many sprained fingers that had to be splinted by the school nurse, I set out to find a “real” job and canvassed the downtown area, looking for work.

On Monday evenings in South Bend, the downtown businesses remained open until 8:30 rather than closing at 5:30. As I canvassed the downtown, I spotted Mr. Forbes, a heavyset middle-aged White man, alone inside his typewriter store. I went in and asked him for a job. “You need some help?” I asked. “What can you do?” “I can do whatever these other boys do,” I said.

I’d passed the store many times and noticed a few older boys, both White and Black, working around the shop. After seeing them, I thought I might have a chance.

Mr. Forbes looked me up and down. “Where do you stay?” “On the Westside,” I answered, referring to the area of the city where the Black population was then concentrated. “When can you work?” “I can work after school and on Saturdays.”

After a few minutes of this back-and-forth, Mr. Forbes agreed to hire me. “Well, I can start you off at fifty cents an hour.” “Can you make that seventy- five?” “Naw, you’ll need to work your way up.” “Okay,” I said, “when can I start?” “You can start tomorrow,” he said. I shook his hand. “All right.” I was elated: this was my first real job, where I would make a weekly wage.

After school the next day I went to the store, and Mr. Forbes introduced me to the other boys, all a few years older, who worked for him.

Over the next weeks, Mr. and Mrs. Forbes would come to know and trust me, and I would come to know them. I would run errands for them like shopping for Mrs. Forbes’s groceries, picking up chop suey from the local Chinese restaurant or fetching sandwiches at lunchtime, and on occasion depositing checks and cash in the local bank. Much later, after I’d gotten my driver’s license, I even delivered typewriters in Mr. Forbes’s new Ford.

The shop was a center of activity, about 350 feet square. The counter was in the front, with typewriters in the display window and stacked on shelves along the sides, a desk, a bathroom in the back, and stairs down to the basement. There was a constant flow of people in and out— customers, students, and older people wanting to rent or buy typewriters. Mr. Forbes was quite the salesman, while his wife typically sat at the desk and took care of paperwork. Their son, Richard, worked there too, selling and renting typewriters or making deliveries. The Forbeses lived upstairs on the third floor of the building.

When things were slow, it might be just Mr. Forbes and his wife and us boys, listening to music on the radio and watching the scene from the large front window. I was very attentive— this was a new world for me. Usually, after arriving from school, I’d empty wastebaskets downstairs and then go to see if Mrs. Forbes had trash to take out. Also, on occasion, I’d paint, fix the concrete out front, and burn trash in the incinerator in the basement, and then settle in behind the workbench to work on

typewriters. I’d observe the scene and listen to the conversations as I did my work.

After I’d worked for Mr. Forbes for a few weeks, the police noticed that the bicycle I’d parked outside his shop was a stolen one. I explained that I hadn’t known I’d bought a stolen bike, and Mr. Forbes vouched for me: “He’s a nice boy.” His trust in me was enough for the White officers.

A sensitive man from a small town in Illinois, Mr. Forbes treated me well; he genuinely liked me and became almost like a father to me. He and his wife even included me on family trips to their cottage by a beautiful Michigan lake. I’d do chores around the cottage, swim in the lake, and eat dinner at their picnic table like a member of their family. As the only Black person at that lake community, I was fascinated by this White world, and I noticed what Mrs. Forbes cooked and how their family ate.

Since I worked in Mr. Forbes’s shop from age twelve until I graduated from high school, I had several years to observe that privileged world. Of course the customers who visited the store were usually White, as were Mr. Forbes’s friends, who would sometimes stop by to talk and socialize. I’d watch the constant traffic in and out of the store and eavesdrop on the conversations. Mrs. Forbes would sit at her desk and do the bookkeeping while the other boys and I would take typewriters apart, soak them in a cleaning solution, wash them down, and reassemble or repair them.

Once, after there had been a fire at the store, we were all working while Mrs. Forbes talked on the phone about cleaning up from the fire. She said, “I never worked so hard in my life—I worked like a n****r.” This comment stopped us boys in our tracks. The room grew deathly silent, and we all tried to ignore what had just been said. Mrs. Forbes caught herself but said nothing more. A few days later, Terry, one of the older Black boys, was in the apartment above the shop, changing a light bulb, when Mrs. Forbes apologized for using the N-word. “Oh, that’s not a problem. I know you

were not talking about me, ’cause I’m not a lowlife,” said Terry. “And, Mrs. Forbes, you are a former schoolteacher, so I know you’re too intelligent to use that word. It must have been a slip-up.”

This was in the late 1950s and 1960s; the civil rights movement was going on, and by the time I was fifteen or sixteen, it was in full swing. People were demonstrating throughout the South, and Viola Liuzzo, a Detroit White woman, was killed in her car in Selma, Alabama, because she was registering Black people to vote. Mr. and Mrs. Forbes and their friends would discuss this incident in the store, and they invariably blamed the woman for not minding her own business. Once in a while we younger people would join in, but the Forbeses often made fun of the demonstrators holding sit-ins, especially when they were dragged away or roughed up by the cops. That seemed funny to Mr. Forbes, who would sometimes mock the demonstrators and pretend he was going to hold a sit-in in his own store if Jim, my younger coworker, and I didn’t behave.

This was how I became aware of what race meant to him. This is the context in which I began to learn how he felt about Black people and their struggles for racial equality: that they were a funny, lowly, and distant people who had strange diseases and were different from Whites. Yet at the same time he was friendly to me.

Once when I was fifteen or sixteen, Mr. Forbes’s son needed his lawn mowed. It was summertime, and things were slow at the shop. Richard and his wife, Irene, lived across town in a nice White neighborhood. I said, “Okay, I’ll do it,” and got ready to leave on my bike. Before I went out the door, Richard called out, “Okay, Eli, Irene’s there. Don’t try anything!” I just waved him off and left.

When someone like Richard said things like that, I was reminded of my place as a Black person in the whole scheme of things. And yet he and the rest of the family were all friendly to me. All these incidents occurred as I was coming of age; gradually, I would pay closer and closer attention to this context and its contradictions.

On occasion Mr. Forbes sent me to other office buildings around the downtown to change typewriter ribbons, giving me an entrée to a host of entirely White establishments. But my real initiation into this White world began in Mr. Forbes’s store and through the experiences that job afforded me.

Then one day my coworker Jim said to me, “Eli, guess what Forbes told me.” I was curious.

“He told me I shouldn’t hang out with the colored boy so much.”

“No, he didn’t say that.”

“Yes, I swear he did!”

I was incredulous and continued to argue with Jim about whether Mr. Forbes actually told him, a White boy, not to hang out with me so much.

Mr. Forbes had been my mentor since he hired me at age twelve. Not only had he taught me how to take apart any typewriter, fix it, and put it back together, he also had absorbed me into the life of the store and his downtown office building where he worked and lived. I ran errands for him and Mrs. Forbes, and I knew not only Richard but his wife, Irene, and their young daughter, Beth. I also knew Mr. and Mrs. Weedling, Mr. Forbes’s tenants; the lawyers Steve Turoc and Paul Paden; and Mrs. Carter, the wife of Dr. Carter, who gave voice lessons on the third floor and whose trash I emptied when I arrived after school each day. I had cordial relations with all these people. Mr. Forbes and these other adults were the first grown White people I had come to know so well. It was clear to me that Mr. Forbes cared for me as a person, and I was sure he liked and trusted me.

After my conversation with Jim, however, I started to watch Mr. Forbes more closely and noticed racial issues I’d previously ignored. I began to see that while Mr. Forbes trusted me, even loved me, and would do almost anything for me, he placed limits on our relationship. In the caste- like system of South Bend, in which Black people were considered the lowliest, he wanted to protect Jim from my status. In effect, he taught me what it means to be Black in the White world.

Soon after this, my interest piqued, I began to notice even more closely how Mr. Forbes and his friends thought about Black people. They stereotyped them, saying Black people carried diseases like tuberculosis more often than Whites. On Saturdays, when Black women came downtown to shop— sometimes heavyset women in brightcolored dresses and fancy feathered hats— Mr. Forbes would stand up in the shop and call, “Look! Look!” as he and his friends peered out the store’s

large front window and mocked these women.

I also observed that these men’s biases didn’t apply just to Black people. Mr. Greene, a tall blond salesman in his late fifties, would sometimes stop by to drink coffee and chat. One Saturday morning when Mr. Forbes had not gone to the Elks Club across the street to play cards the night before, he asked Mr. Greene who else had been there. Mr. Greene replied, “Four guys and three Jews.” I overheard this comment from my workbench, and now I began to see prejudice that was directed not just against Blacks but against others too.

I noticed contradictions in Mr. Forbes’s behavior as well. For example, I never heard him correct Mr. Greene on that remark, yet Mr. Forbes had Jewish friends. And while generally appearing to accept me and to treat me well enough around the shop, he seemed concerned that my social stigma might rub off on Jim, and Jim seemed to know this as well.

I’d been raised to consider myself equal to anyone, and my parents had encouraged me to see that good and bad people come in all races, but to not tolerate disrespect. My neighborhood friends were not only Black boys but also White boys like Jim, as well as ethnic White children whose families were recent immigrants from Poland and Hungary, though we children were often more accepting of one another than the adults were; we played together.

I gained tremendous insights during my teen years as I spent time both in my family’s home in a Black neighborhood and in the Forbes family’s White world. I lived within and on the margins of both spaces during this time, and I became an attentive observer of both.

I never confronted Mr. Forbes about what he might have said to Jim, but as a high school student, and especially during a period of rising racial consciousness, I did question other White men. Once when changing a typewriter ribbon at a large real estate company, I asked the elderly founder why there were no Black people working in his business. He said candidly that his current employees would quit if he hired Black people.

As I worked for Mr. Forbes, I came to realize that he and the other White people there liked me most when I was in my place. In fact, he once told me directly, “Eli, you can go far in this world; just keep your nose clean and don’t cause trouble.” In other words, “Don’t get out of your place.” Thus, as a young boy, it gradually dawned on me that in South Bend and perhaps throughout America, there were places where I and my kind might not always be welcome.

***

Through these and many other experiences, I became aware that because I was Black, the White world was a problem I needed to come to terms with. I learned that the color line was ever- present, but that it was a delicate and problematic thing, at times almost hidden but bright as day the moment it was crossed.

In some ways this country has made great strides about race since South Bend in the 1960s. But in other ways, the nation has hardly moved forward at all. This book grows out of a lifetime of the professional observations of a sociologist and an ethnographer, and the personal experiences of a Black man in America. Using a combination of ethnography, interviews, and incidents from my own life, I’ll show just how enduring the color line is for Black people in America: how “White space” comes into existence and makes life difficult for Black people, and how the negative power of the iconic ghetto is a constant in Black life. In a word, as a young Black man working for Mr. Forbes, I learned my “place.”

***

Born in a cabin on what used to be a slave plantation in the Mississippi Delta, delivered by my grandmother as the midwife, my family migrated two years later to South Bend, Indiana, where I began my ascent, moving from the Black ghetto to studying at Indiana University, the University of Chicago, and Northwestern University, to teaching at Swarthmore College, the University of Pennsylvania, and Yale University—where I am a Sterling Professor, the highest academic honor Yale can bestow on a member of its faculty. Hence, I have made my way from the symbolic bottom of American society to the symbolic top. Strikingly, the iconic Black ghetto has followed me every step of the way. I have kept memories of my journey and taken qualitative field notes along the way. My long-term qualitative fieldwork in cities along with the lived experience of Blackness have contributed profoundly to the ethnography that is ultimately reflected by this work.

Elijah Anderson is the Sterling Professor of Sociology and of African American Studies at Yale University, and one of the leading urban ethnographers in the United States. His publications include Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City (1999), winner of the Komarovsky Award from the Eastern Sociological Society; Streetwise: Race, Class, and Change in an Urban Community (1990), winner of the American Sociological Association’s Robert E. Park Award for the best published book in the area of Urban Sociology; and the classic sociological work, A Place on the Corner (1978; 2nd ed., 2003); The Cosmopolitan Canopy: Race and Civility in Everyday Life was published by WW Norton in 2011. Anderson’s most recent ethnographic work. Black in White Space: The Enduring Impact of Color in Everyday Life was published by the University of Chicago Press in 2022. Additionally, Professor Anderson is the recipient of the 2017 Merit Award from the Eastern Sociological Society and three prestigious awards from the American Sociological Association, including the 2013 Cox-Johnson-Frazier Award, the 2018 W.E.B. DuBois Career of Distinguished Scholarship Award, and the 2021 Robert and Helen Lynd Award for Lifetime Achievement. And, he is the 2021 winner of the Stockholm Prize in Criminology.