Soda Policies and Social Anxieties

Melina Packer

Two recent public health campaigns exemplify the representational politics embedded in anti-soda efforts.

Source: Fatsmack campaign, Boston Public Health Commission

Science and Stigma

Sugar is the new tobacco. Or is it? Prominent medical physicians and public health advocates in the United States would have us believe so. Scientists link consumption of sugar to increased rates of preventable death from metabolic disorders and cardiovascular disease. Soda in particular has become the target of numerous public health campaigns across the country. Research suggests, for instance, that drinking one 12-ounce can of soda per day increases the risks of heart disease and type 2 diabetes by approximately 30 percent. Following the trajectory of anti-smoking campaigns, professional advocates are increasingly pushing for municipal, state and national level soda taxes as a means of reducing soda consumption, and, presumably, improving public health. Their visual and discursive interventions unfortunately tend to produce problematic representations of soda drinkers.

Two recent public health campaigns exemplify the representational politics embedded in anti-soda efforts. In late 2011, the Boston, Massachusetts public health commission sponsored (with support from the US Department of Health and Human Services) a series of print and video advertisements against soda consumption, including an accompanying website, entitled “Fatsmack.” In 2014, a coalition of public health advocates in the city of Berkeley, California campaigned for a municipal tax under the slogan: “Berkeley vs. Big Soda.” Fatsmack visuals can still be accessed via the Internet at fatsmack.org; Berkeley successfully passed the $.01 per ounce soda tax measure in November 2014. Here I critically compare the visual and written rhetoric of Fatsmack and Berkeley vs. Big Soda to demonstrate how US dietary advice is laden with, and reproduces, problematic narratives.

Rather than penalize or regulate the producers who create, market and profit from soda, for instance, soda taxes place a disproportionate amount of both the blame and the burden on (low-income) consumers who purchase, drink and may be made ill by sugary beverages.

I do not deny that excess sugar consumption produces adverse health effects, nor do I dispute the fact that lower-income populations face disproportionately worse health outcomes on average. I do, however, interrogate these campaigns’ assumption that personal health is principally a matter of dietary “choice,” as well as their (re)production of one ideal/normal/healthy body. As the ensuing analysis demonstrates, poor people of color are repeatedly invoked in these campaigns as agency-lacking subjects most in need of help and most (potentially) deviant from bodily “norms.” I further argue that taxing soda remains a single-axis “solution” to intersectional problems. Rather than penalize or regulate the producers who create, market and profit from soda, for instance, soda taxes place a disproportionate amount of both the blame and the burden on (low-income) consumers who purchase, drink and may be made ill by sugary beverages. A more justice-oriented approach to (soda) policy might instead support all peoples’ access to pleasurable diets, by mitigating the vast and deep power and wealth asymmetries that render certain populations less healthy than others. Tackling the structural preconditions which (re)produce socioeconomic disparities in health, in ways that both avoid blaming the “victim” and de-center white, middle-class norms, would draw attention and resources to real (bodily) suffering while also creating spaces and action for more collective, justice-centered solutions. Public health inequities, including but not limited to the disproportionate burden of metabolic and cardiovascular disease, would be far better treated through poverty alleviation and the downward redistribution of resources, than by stigmatization of a certain drink, and with it, a particular body.

The Cult of Normativity

The tendency of experts who dominate the US soda tax discussion to occupy markedly different social positions than the targets of their dietary reform efforts perpetuates structural power imbalances. A close analysis of Fatsmack and Berkeley vs. Big Soda’s campaigns reveals public health advocacy’s proclivity to prioritize the concerns and perspectives held predominantly by the white (male) middle-class. Based upon Boston and Berkeley advocates’ visual and rhetorical choices, soda tax proponents seem to remain largely ignorant of, or insensitive to, this country’s histories and contemporary practices of curtailing, shaming, monitoring and policing lower (and immigrant) classes’ eating cultures.[1] Moral panics around sugar consumption have broader implications beyond the individual consumer. Arguably, fat people become scapegoats for various contemporary US social “crises,” such as the disappearing middle class—who may cling to dietary propriety as their only remaining means of distinguishing themselves from the poor—or the shrinking white majority—some of whom believe that black and brown (and particularly reproductive female) bodies are simply taking up too much space.

Biomedical physicians and professional consumer advocates have widely publicized their pro-soda tax positions since the 1990s, including such reputable and powerful institutions as the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity and the DC-based firm Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI). Rallying around the so-called obesity epidemic,[2] soda tax advocates soon included prominent public intellectuals among their ranks, such as best-selling writer Michael Pollan, and cookbook author and New York Times columnist Mark Bittman. Without delving into the politics of fat, it is worth noting how “Health At Every Size” physicians and other self-identified fat activists have deftly argued that BMI (body mass index), the equation used to create and monitor obesity statistics, is an inherently flawed measurement tool, and that heaviness does not necessarily signal nor lead to ill health.[3] Researchers have also compellingly revealed how fatness comes to signify, or becomes the scapegoat of, historically contingent social anxieties, ranging from rising immigration rates, to expansions of women’s rights, to increasingly ambiguous class distinctions.[4] Here I emphasize the productive work of defining and representing normative bodies, or how Fatsmack especially, and to a lesser extent Berkeley vs. Big Soda, reproduce this problematic normativity.

Because the US-based cult of thinness judges girls and women more harshly for fatness than boys and men, the following analyses focus primarily on how gender intersects with weight/health, race/ethnicity/culture and class, though a variety of other axes are worthy of exploration, including sexuality[5] and motherhood.[6] Although advocates in Boston, Massachusetts did not pursue taxation, I begin my critique with Fatsmack because this campaign’s rhetoric (indeed, the very name) exemplifies the pitfalls and prejudices (re)produced by a single-axis approach–focusing solely on soda, in isolation from the plethora of other, more systemic factors that contribute to ill health.

Rhetoric and Representation: Fatsmack

The most prominent visual element on the website’s 2011 homepage[7] was the auto-rotating carousel of images, beginning with the whimsical yet ominous graphical pronouncement: “Don’t Get Smacked By FAT,” the word “fat” greatly emphasized in size, shape and color.

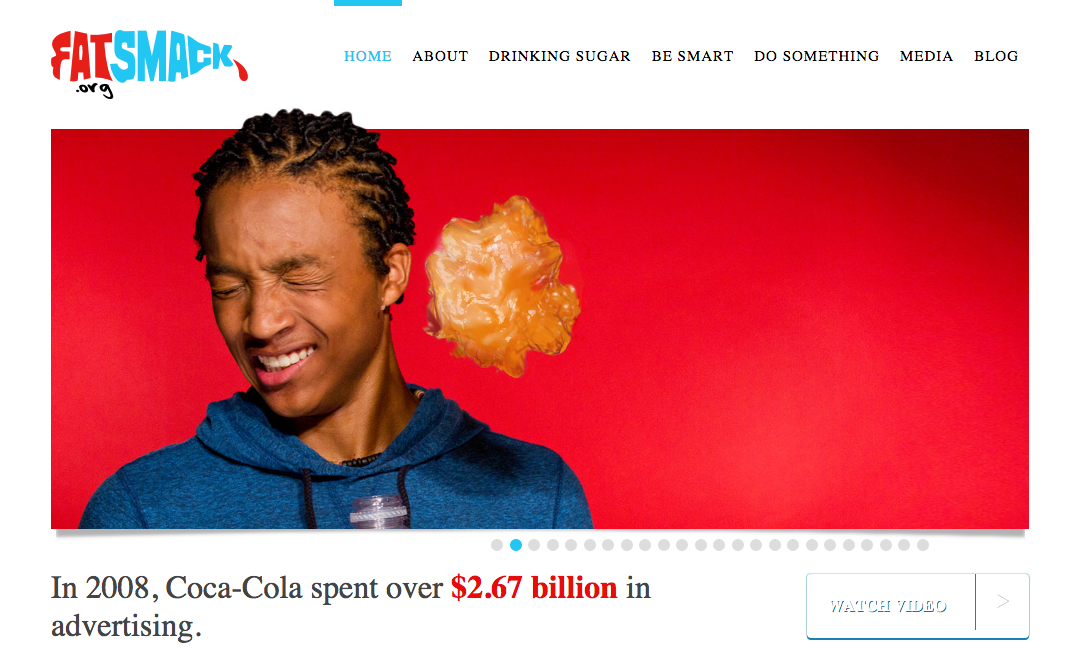

Beneath each image, a similarly sober statistic, in large heading-style text, changed along with each carousel slide, warning for example: “More than 40% of Boston Public School students are overweight or obese.” The proceeding four slides depicted youth of color, who appear, at least from the shoulders up, to be thin-bodied. The first two youth are boys who present as African American, one sporting a blue hooded sweatshirt and corn-rowed hair, wincing in pained and disgusted anticipation as he is about to be “smacked” upside the head with a large, moist, fleshy yet alien-looking globule of disembodied fat.

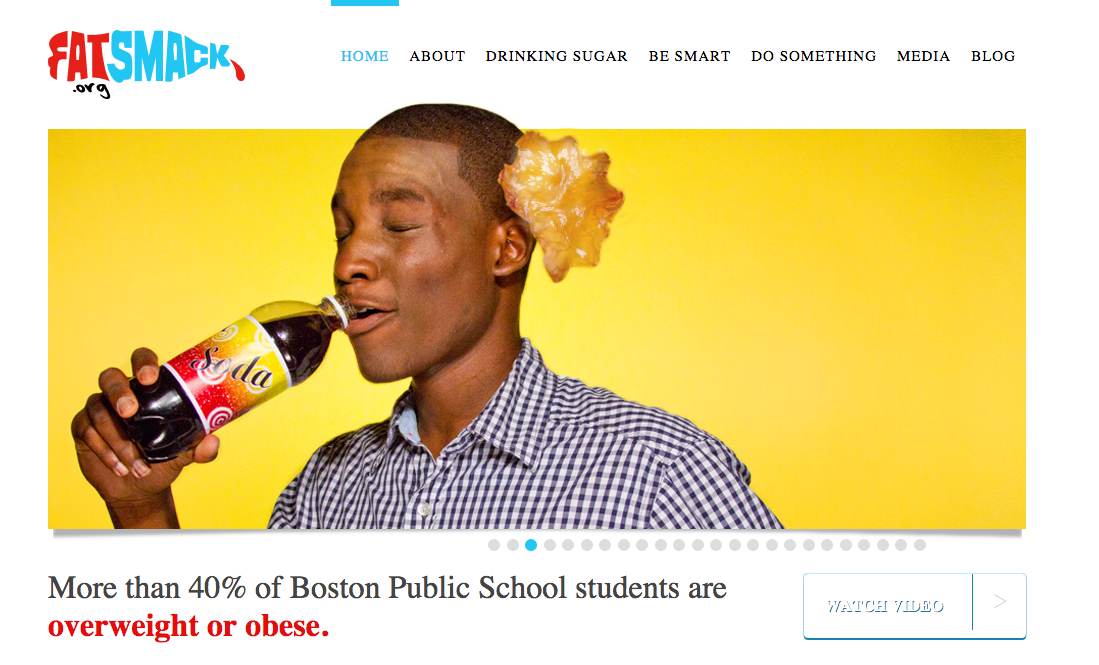

The second African American young man, who has closely cropped hair and wears a button-down, collared shirt, also winces in unpleasant anticipation as he is caught, drinking mid-sip from a generic plastic bottle of dark soda (invoking the three largest soda corporations’ signature drinks: Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Dr. Pepper), by another projectile of a disembodied, gelatinous blob of fat, also about to “smack” him upside the head.

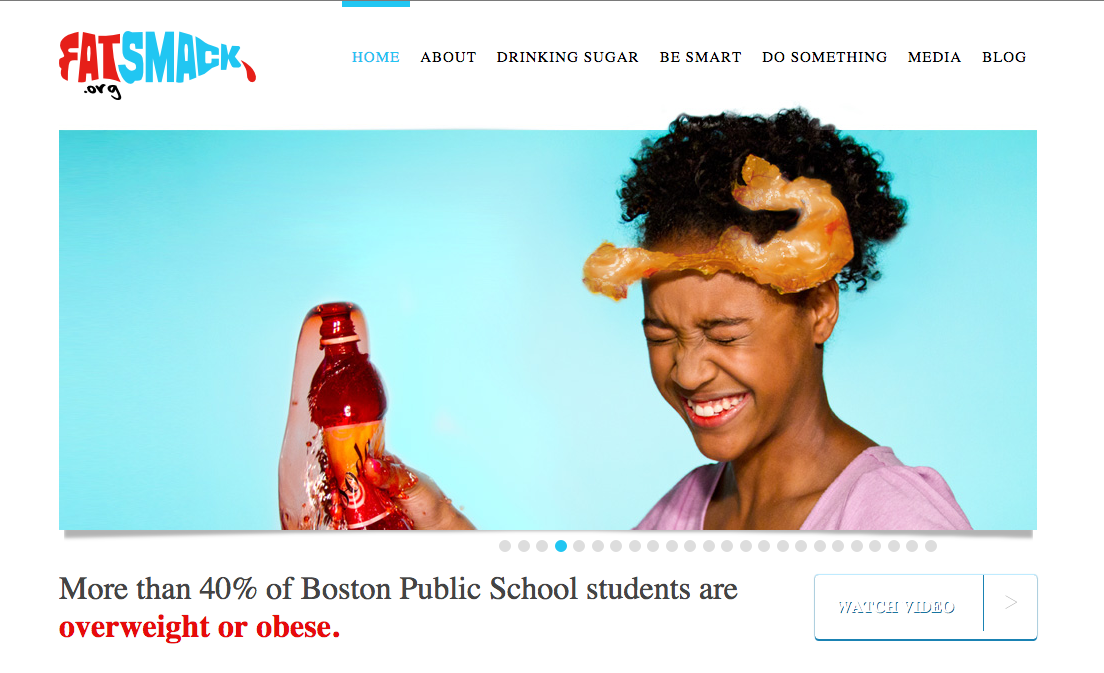

The next two youth of color are girls, who are positioned and posed quite differently. The first young woman (and third youth) depicted in this carousel of images also presents as African American. She wears a low-necked pink shirt, exposing more of her skin than that of the two boys; her hair is naturally curly and pulled back from her face in a playful ponytail. This young woman of color is also interrupted in her soda drinking, but unlike the boys of color who grimace in anticipation of violence, this girl seems caught in laughter, smiling widely as the suddenly phallic soda bottle explodes and overflows (a translucent orange or light brown liquid this time) over her tightly clenched hand, and as the fat—in this image more elongated than circular—lands on her forehead in an uncanny resemblance to the pornographic “cum shot.”

The second girl (fourth youth) of color also appears to be caught interrupted/aroused by fat, in a moment of erotic surprise and pleasure. Her mouth is wide open as she brings an orange-ish, phallic soda bottle to her lips; her gaze looks coyly at the viewer (she remains the only youth whose eyes are not tightly closed), as she gasps in wide-mouthed excitement while the fleshy, wet, amorphous fat explodes all over her adolescent chest, which is thinly concealed in a tightly-fitted, low-necked, cap-sleeved t-shirt.

The Boston Public Health Commission’s inclusion of youth of color is less a well-intentioned attempt at multiculturalism than an indication of city officials’ privileged social positions and elite epidemiological training: children of color, particularly those in public school, are understood as both the most “at risk” for obesity (read: ill health) and the most “in need” of education (read: civilizing). Black boys are figured in positions of reprimand, abuse and emasculation, while black and brown girls are both sexualized and infantilized. Overall, these youth of color are positioned as poorly informed soda indulgers, who should obediently self-regulate in order to become more proper, productive, conforming US subjects. Notably, no white youths appear on this website’s image carousel.[8] The thinness of these youth of color further suggests that it is soda alone which produces fat bodies, detracting attention from the variety of different stressors that contribute to ill health (irrespective of weight), including several other, and potentially more harmful, adverse health outcomes of sugar consumption (which too remain unrelated to weight, e.g. tooth decay, metabolic dysfunction).

Deeper into the Fatsmack website, several other, less problematic images may be found. The written text also shifts, from mocking, scaring or scolding the doomed-to-fatness soda drinker, to highlighting the dangers of type 2 diabetes—arguably a far greater threat to health and a disorder that is not necessarily marked by fatness—and criticizing soda corporations’ predatory marketing tactics and obscene profits. For example the page titled “Be Smart,” which accompanies the heading “The Beverage Industry: Don’t Get Played,” shows a young African American-presenting man in a button-down plaid shirt and eye-glasses, gazing directly at the viewer with his hand defiantly held forward as if to say “stop.”

However, even this slightly more empowering messaging, both visual and written, shoulders the burden on individual subjects rather than corporate entities or government regulators. Tellingly, the website’s “Do Something” section instructs readers to drink water, rather than, say, pressure one’s elected officials to restrict corporate marketing or limit sugar content by volume, two possible policy responses which neither force the consumer to pay more nor burden/stigmatize certain populations.

Fatness, meanwhile, remains completely abject. Fat itself is disembodied and dehumanized while fat-bodied people themselves are absent from view, yet somehow, somewhere, lurking from beyond the image frame.[9] An implicit threat hovers over these pages: if you don’t change your (presumed) bad habits, if you don’t do as you’re told (by social elites), you will be smacked by fat–become a disgusting figure who drains the public coffers. One might argue that Fatsmack’s visual absence of fat people is preferable to the “headless fatties” that proliferate media reports on the “obesity epidemic,” or the forlorn fat children depicted in Georgia’s infamous anti-obesity campaign. While the omission of fat-bodied people is perhaps a lesser evil than the inclusion of abjectified, decapitated fat bodies, a justice-oriented public health campaign would avoid either valorizing or denouncing any particular body shape, size or shade.

Even if fatness were unequivocally unhealthy, the presumption that low-income populations eat more or worse than higher-income populations simply does not bear out in national surveys. All USDA-defined income brackets consume approximately the same quantities and types of calories, while non-Hispanic white adults reportedly drink more soda on average than Hispanic and black adults combined. Statistical split-hairs aside, the pressure on individuals to monitor and manage their own weight (read as health), against all odds, relieves governments of responsibility for the structural and institutional inequities that create and maintain low-income neighborhoods (and prohibitively expensive nutritious food and healthcare) in the first place.

Reflexive Yet Restricted: Berkeley vs. Big Soda

The striking absence of fat-shaming and obesity fear-mongering in Berkeley, California’s 2014 soda tax campaign marks a different historical moment and location. Perhaps learning from the unfavorable reactions to Boston’s Fatsmack, Georgia’s anti-childhood obesity campaign, or New York City’s “Pouring on the Pounds” advertisements, Berkeley soda tax advocates eschewed shock value for a more hopeful, communitarian, even justice-oriented message, captured by their court-case-like name: Berkeley vs. Big Soda. Additionally, the biomedical research linking soda consumption to health issues has shifted since 2011 (when Fatsmack was disseminated), producing strong evidence that: excess sugar consumption leads to cardiovascular and metabolic diseases irrespective of weight;[10] and that such diet-related illness rates are not necessarily higher among lower-income populations.[11] Berkeley vs. Big Soda, or YES on Measure D, not only garnered support from both public health officials and a diversity of local residents, but also focused their visual and written campaign on the culpability of corporate firms: “Big Soda.” Rather than shame and blame the (fat, brown, poor) “victim,” Berkeley vs. Big Soda pointed their collective finger at the powerful perpetrators: Coca-Cola Corporation, PepsiCo and Dr. Pepper/Snapple Group.

Nevertheless, in my view this relatively compassionate campaign still missed the mark. The encouraging, participatory-democratic potential of Berkeley vs. Big Soda fell short of restricting and regulating the corporate powers that exert so much negative influence over our individual and collective well-being. While “Big Soda” spent millions in a failed attempt to reject Berkeley’s city policy, citizens still bear the cost of the tax, and like all sales taxes, this cost disproportionately burdens those with lower incomes. Measure D does encourage Berkeley’s city council to appropriate soda tax revenue towards childhood health and education programs, but this earmark is more suggestion than written law. (Berkeley advocates strategically did not write earmarked funds into the bill because passage of such a law would have required a two-thirds majority.) Assuming Berkeley council members do indeed funnel collected funds into children’s programming, ironically more money for children means more soda is being consumed. Despite Berkeley vs. Big Soda’s laudable attempts to avoid fat-shaming, I contend that a more justice-oriented approach to sugary beverage “choice” and public health would have instead emphasized structural impediments to healthy and happy living, rather than narrowly focus on a single product and artificially flatten the varying heights from which we all begin.

The Berkeley vs. Big Soda graphic is uplifting and playful, featuring an energized group of (slim-bodied, active) youth of various heights, who together declare “YES” on Measure D, showing their physical, affirmative support.

These children, of no marked race, present as healthy-bodied and engaged citizens, who enthusiastically participate in local policymaking processes. Notably, the Berkeley vs. Big Soda website text focuses on (type 2) diabetes rather than obesity, and gives equal, front-page emphasis to the campaign’s foci: health concerns; support received from myriad “[r]espected health and community leaders” and; critiques of corporate firms’ excess wealth and political influence. Unlike Fatsmack, which buried their corporate criticisms, campaign funding and individualizing messages behind and beneath their problematic, phallic images of “FAT” attacking and seducing youth of color, Berkeley vs. Big Soda immediately presents itself as concerned with the internal health of all children, supported by a diverse community and committed to policy change rather than mere behavior modification, while also externally shifting (some of) the blame onto corporations.

Similar to Fatsmack, and in unison with broader US narratives demonizing sugary drinks, Berkeley vs. Big Soda stigmatizes a particular product, and, in turn, those who drink it. Soda consumption/enjoyment, like smoking, becomes marked as a deplorable, “low-class” habit, as seemingly only low-income people are uneducated or gullible enough to continue consuming such an unhealthy item (and must be disciplined monetarily). Indeed, national soda tax advocates’ response to the regressivity argument betrays a certain bourgeois white savior complex: “the poor are disproportionately affected by diet-related diseases and would derive the greatest benefit from reduced [soda] consumption.”[12] To the chagrin of several progressive soda tax proponents, groups such as the NAACP and the Hispanic Federation publically opposed tax proposals in Richmond, California and New York City, positing instead that the poor “would derive the greatest benefit” from broadly supportive economic policies as opposed to sanctions (especially given that small and minority-owned businesses tend to have narrower profit margins than corporate retailers).

Absent problematic images of certain races and bodies, and thus largely avoiding the gendered intersections within and between race and weight, Berkeley’s campaign remains most troubled by class (including the conflation of poor and of color). Unlike Richmond and New York City, Berkeley vs. Big Soda gained the support of the NAACP, as well as local Hispanic organizations. Xavier Morales, executive director of Latino Coalition for a Healthy California, responded publically, and powerfully, to the oft-repeated regressivity argument (which, ironically, industry lobbyists such as the American Beverage Association also levied), asserting that (type 2) diabetes is regressive.

The … point about the regressivity of the [soda] tax to communities of color and to poor communities, just makes me mad.

It reminds me of the time when I was a graduate student studying in New York and had to come home to say goodbye to my aunt who was dying from complications of diabetes. I can still hear the urgency in my mother’s voice as she asked me to come see her sister one last time. I vividly remember walking into her room and seeing her in the hospital bed with both legs amputated at the thigh and a colostomy bag hanging at her side. … She put up a hard fight, but the disease took her less than a week later. This is what I think about when I hear industry say the [soda] tax is regressive against people of color and also to the poor. My aunt was both.

Many of us in the Latino community know first-hand what death and debilitation from diabetes looks like. We also know what it feels like to be lied to and when people are trying to confuse the truth and manipulate us into doing something against our own interests.

I refuse to be confused; I refuse to be manipulated; I’m voting Yes on Measure D.

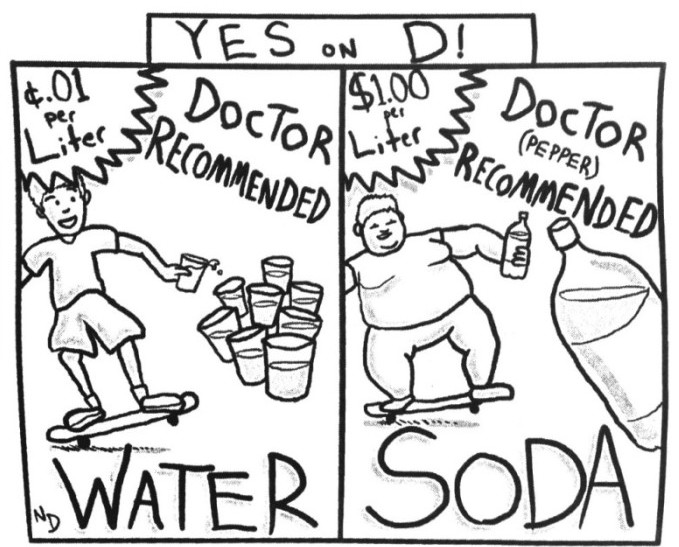

I do not deny the lived experiences of Morales’s aunt and others who have suffered from the ravages of type 2 diabetes, among other preventable illnesses, along with poverty. Nor do I mean to suggest that fatness is completely benign; excess weight can signal medical issues and/or produce physical discomfort. My criticism is that tax-as-solution, similar to education-as-cure,[13] not only does little to mitigate corporate power and regulatory capture, but also further stigmatizes those who are repeatedly invoked by scientific and popular media as “at risk,” namely people of color, people of size and the poor (and, in regards to fatness, women and mothers especially). Moreover, the soda tax absolves governments of their responsibility to address wealth and health disparities at their source, namely neoliberal, post-industrial capitalism and its threadbare, patchwork social safety net. And despite Berkeley’s best efforts at avoiding divisive obesity rhetoric, the cognitive and conceptual slippage between obesity and type 2 diabetes remains common. For example, speakers at a September 2014 campaign event, sponsored by Berkeley vs. Big Soda, framed the tax in terms of the US “obesity epidemic.” Additionally, the Berkeley Times, a local, print-only paper, published a cartoon in support of the soda tax, juxtaposing a thin-bodied (white?) boy drinking water against his alter-ego/fat-bodied self drinking soda.

The Policy Implications of Problematic Representation

Anti-soda campaigns are primarily about messaging, especially given that a soda tax alone will not solve socioeconomic disparities in health. Fatsmack’s representations were particularly perverse, visually policing certain bodies as defiled and thus (re)producing both normative bodies and normative, (neoliberal) self-regulating citizens. Even a campaign as sensitive as Berkeley vs. Big Soda functioned through problematic tropes of the proper, sugar-free citizen. Those of us interested in public health should not reproduce normative bodies within the very medium of our campaigns. Rather, advocates would do well to attend to power: who has the privilege of levying taxes and at whose expense? Why not advocate for public policies that address health concerns at their root, targeting such systemic issues as poverty-level wages, for-profit medicine and unaffordable housing, to name but a few?

Who has the power to visually police and scientifically stigmatize “other” bodies, and how are their interests served by such othering?

A social justice-oriented policy approach might instead embrace difference, honor individual and collective agency, and draw equitably and reflexively from a diverse set of social positions and self-identified needs. Such nuanced public health campaigns might “let us drink soda,” and even let us be(come) fat, provided governments generate and guarantee the structural conditions within which all subjects have equal and equitable access to a thriving wage, a pleasurable diet (however one defines that), affordable healthcare, and a nurturing environment (supportive of minds, bodies and relationships). Advocates might make the somewhat radical claim—and pursue trans-agency regulations accordingly—that health is much more complex than dietary intake and body weight alone, including such diverse factors as genetics and generational poverty. To be sure, public health professionals are not ignorant of these complexities. The Berkeley vs. Big Soda campaign has been especially reflexive, intentionally building a grassroots coalition that targeted corporations rather than shaming (fat) soda drinkers, and critically assessing their own campaign strategies. [14] And Morales’s self-identified needs were indeed articulated in this case. However, the persuasiveness of the dominant narrative regarding who and what constitutes an ideal, healthy body must be accounted for. Who has the power to visually police and scientifically stigmatize “other” bodies, and how are their interests served by such othering?

Sister scholars Jessica and Allison Hayes-Conroy call for a feminist nutrition practice, one that both unveils the white/Western core of nutrition “facts,” and troubles how health itself is defined and measured:

[U]nique stories matter to the practice of nutrition. They signal – forcefully, starkly – that a universal answer to the question “what’s good to eat?” is both academically sloppy and socially unjust. … Thus, rather than a distinct and pre-determined set of core values and goals, nutrition becomes a collective, negotiated process of transformation towards healthier people and communities (original emphasis).[15]

The reflections above suggest that a justice-oriented approach to disparities in social and physiological well-being would neither tax nor demonize soda, but rather reign in the corporate control which exerts downward pressure on wages, exacerbates ecological harm and perpetuates socio-structural violence. While a social justice focus still allows space for dietary guidance, perhaps the most transformative public health policy of all has little to do with food and drink. If the message that X is (un)healthy must be broadcast, then why not craft campaigns and regulatory responses directed toward the entire public, complemented by a nuanced awareness of the layered degrees of agency particular subjects employ within their historically specific contexts and structurally contingent socioeconomic positions? Peoples’ dietary practices are not merely for health. Sustenance also sustains cultures, religions, families and personal pleasures. Let us imagine into reality a practice of public health advocacy and policymaking that creates hopeful possibilities for both social equity and just desserts.

References and Footnotes

- Biltekoff, Charlotte. Eating Right in America: The Cultural Politics of Food and Health. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013; DuPuis, E. Melanie. “Angels and Vegetables: A Brief History of Food Advice in America.” Gastronomica 7, no. 3 (August 2007): 34–44. doi:10.1525/gfc.2007.7.3.34; Tompkins, Kyla Wazana. Racial Indigestion: Eating Bodies in the Nineteenth Century. America and the Long 19th Century. New York: New York University Press, 2012. ↩

- There is extensive public and scientific debate as to whether obesity statistics are inflated; skeptics critique the methodology of both Body Mass Index (BMI) and prevalence rates, as well as the conflation of weight and health. See for example Fat Politics by J. Eric Oliver (2005). ↩

- Bacon, Linda, and Lucy Aphramor. “Weight Science: Evaluating the Evidence for a Paradigm Shift.” Nutrition Journal 10, no. 1 (January 24, 2011): 9. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-10-9. ↩

- Biltekoff, Eating Right in America; Bordo, Susan. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. 10th anniversary ed. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 2003. ↩

- McPhail, Deborah, and Andrea E. Bombak. “Fat, Queer and Sick? A Critical Analysis of ‘Lesbian Obesity’ in Public Health Discourse.” Critical Public Health 0, no. 0 (December 17, 2014): 1–15. doi:10.1080/09581596.2014.992391. ↩

- Friedman, May. “Mother Blame, Fat Shame, and Moral Panic: ‘Obesity’ and Child Welfare.” Fat Studies 4, no. 1 (January 2, 2015): 14–27. doi:10.1080/21604851.2014.927209. ↩

- The city’s Public Health Commission (BPHC), funded in part by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), launched their media campaign in 2011. The above images and text were taken from their website in late 2014, which has since changed significantly in terms of form (though the content remains the same). ↩

- As reported by The Atlantic in 2013: “According to Boston city data, the priority was reaching minority teens. They focused primarily on “13 to 19-year-olds of color, with the target being more skewed towards males,” said Ann Scales, BPHC's Director of Communications during Fatsmack.” ↩

- Pausé, Cat, Jackie Wykes, and Samantha Murray, eds. Queering Fat Embodiment. Queer Interventions. Farnham, Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2014. ↩

- O’Connor, Laura, Fumiaki Imamura, Marleen A. H. Lentjes, Kay-Tee Khaw, Nicholas J. Wareham, and Nita G. Forouhi. “Prospective Associations and Population Impact of Sweet Beverage Intake and Type 2 Diabetes, and Effects of Substitutions with Alternative Beverages.” Diabetologia, May 6, 2015, 1–10. doi:10.1007/s00125-015-3572-1. ↩

- Mozaffarian D, Rogoff KS, and Ludwig DS. “The Real Cost of Food: Can Taxes and Subsidies Improve Public Health?” JAMA 312, no. 9 (September 3, 2014): 889–90. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.8232. ↩

- Brownell, Kelly D., and Thomas R. Frieden. “Ounces of Prevention — The Public Policy Case for Taxes on Sugared Beverages.” New England Journal of Medicine 360, no. 18 (April 30, 2009): 1806. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0902392. ↩

- Hayes-Conroy, Allison, and Jessica Hayes-Conroy, eds. Doing Nutrition Differently: Critical Approaches to Diet and Dietary Intervention. Critical Food Studies. Farnham, Surrey, England ; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013. ↩

- Somji, Alisha et al. 2016. Soda Tax Debates in Berkeley and San Francisco: An Analysis of Social Media, Campaign Materials and News Coverage. Berkeley Media Studies Group. Retrieved January 30, 2016 (http://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/soda-tax-debates-berkeley-san-francisco-news-social-media-analysis). ↩

- Hayes-Conroy, Doing Nutrition Differently, 178-179. ↩